How I spent my summer vacations

It’s been a busy year for Fairbanks Fodar. This blog gives an overview of how I’ve spent much of my past two summer vacations, which, especially given my new-found employment status, suggests to me that summer vacations are an outdated concept in my life.

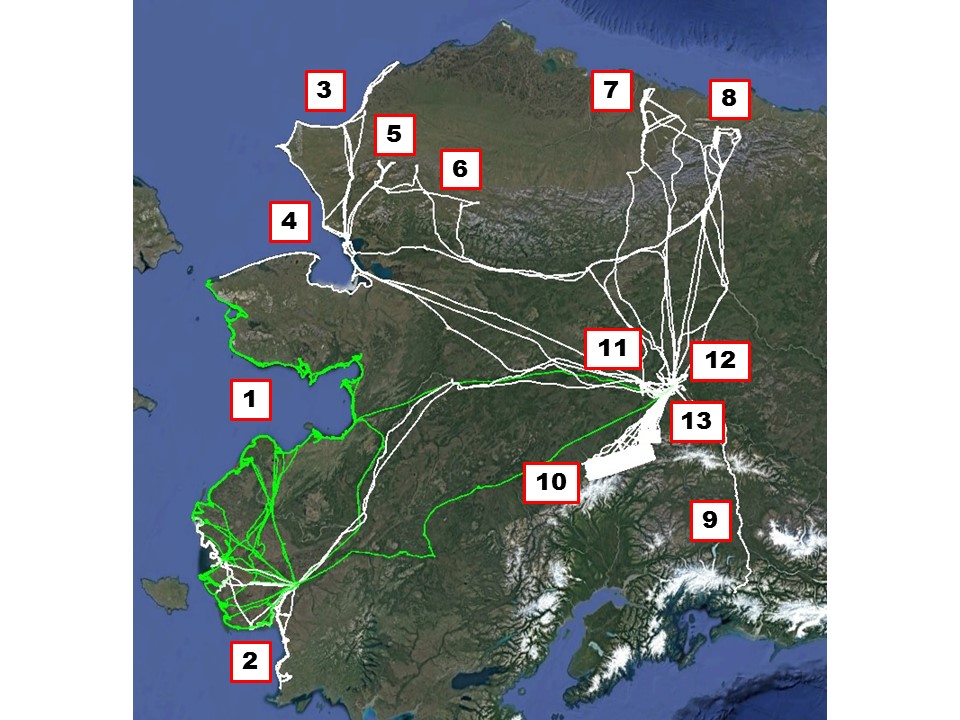

Between 31 July 2015 – 30 September 2016, Fairbanks Fodar flew over 450 hours of mission flying throughout the State. Don’t try this with a drone…

1. A mile-wide swath of coast from Wales to Bethel

An RFP from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources had the audacious goal of mapping a mile wide swath of coast between Wales and Bethel at better than 20 cm resolution, starting in August 2015, for less funding than Trump’s toupee. Fairbanks Fodar rose to the challenge by meeting the specs and delivering the final results well ahead of schedule, minus the orange horse hair. For projects smaller than 1000 km2, we had by now proven repeatedly that our techniques were superior to the alternatives, but this project demonstrated that we can scale those results to any spatial coverage of interest. This project led directly to a project extension to continue the mapping south to Platinum (project #2 in the figure) from DNR and an RFP award from USGS to continue north to Pt Lay (project #3).

This project led directly from some preliminary work we had done the year before:

New papers published on fodar measurements of Alaskan coastlines

The project itself took six weeks of flying, so lot’s of opportunities for blogs:

A Mile Wide and a Micron Deep — Mapping the Coastline from Wales to Bethel

You can also fly around over most of the coastal village data in Fodar Earth.

2. A mile wide swath of coast from Bethel to Platinum

Based on the success of our Wales to Bethel work, in spring 2016 state DNR extended our contract to continue the project to the south, all the way to Platinum.

3-4. Completing the west coast of Alaska

Based largely on our prior success to the south, we won an RFP from the USGS to make a similar map of the north-western coast of Alaska from Point Hope to Point Lay. While waiting for better weather there, we had some time on our hands so we mapped all the way to Wales on our own dime, creating a continuous map of the entire west coast of Alaska, just because we could. In total, our west coast of Alaska coverage is longer than the east coast of the US, and all acquired at low tide!

5. Repeating oblique airborne imagery from 60 years ago

In the early 1950s, some intrepid and foresighted photographers and pilots acquired large format photos of the western Brooks Range. Their imagery serves as the best baseline photography for assessing landscape change in this region of the Arctic. We won an RFP from the National Park Service to repeat this photography for that purpose. So we turned our system on its side as a demonstration of our flexibility and our commitment to Arctic science.

6. Tracking permafrost melt in the Noatak National Preserve

With awards from two separate RFPs from the National Park Service, we mapped six thermokarst slumps, most of which we had mapped previously and so could measure change over time. There is no better time-series of such degradation anywhere.

The Peters Lake project is an enormous and comprehensive one, of which my data forms a small part. These blogs tell the tale of the acquisitions, but soon I hope to share the tales of the data itself.

9. Mapping the entire Richardson Highway

Following the success of our Dalton Highway work, we received a contract from Alaska Department of Transportation to map about 30 miles of the Richardson Highway near Valdez. Along the way, I decided to map the entire thing from Fairbanks and back, just because I could. I believe this is the first time an entire Alaska highway has been mapped at 10 cm resolution, but I could be wrong. In any case, I’m certain it wont be the last, and I think DOT agrees.

10. Mapping Denali National Park

Following up on our success mapping sketchy areas of the road that runs through Denali National Park and Preserve, we were awarded a large contract to map a huge area of the Park at 25 cm resolution, as well as map the road several times at 10 cm. The success of this work led to several small pickup projects this summer where unplanned mass movements were occurring, as well as winning another RFP to do it all over again next year to detect change. The data were delivered about a month ago, so stayed tuned for a blog on the what the best map of Denali looks like.

11. Measuring ice jam dynamics for public safety

This project is one of those that is so cool and useful to the public that it’s worth doing for free.

12. Mapping city roads for DOT

We received a contract from Alaska Department of Transportation to map several roads in the Fairbanks area at < 10 cm resolution. I haven’t had the chance to blog about the results yet, but the data delivered several months ago now have since been used to form the most spatially intensive field validation of our data which — guess what? — showed exactly what we have always found, that it just doesn’t get any better than this.

13. Mapping Usibelli Coal Mine

While we dont have any blogs on this project at the request of UCM, we had a contract this year to map the mine five times. Nobody has complained about the usefulness of the data so far…

Though this blog is of Ft Knox gold mine, it gives the general idea of what’s possible at any mine.

What’s next?

We’ve already won RFPs from the National Park Service and Department of Defense for sizable projects next year, but with so many so many happy clients and so much topography needing to be mapped in Alaska, I suspect this is the tip of the iceberg and I’m expecting to have to turn work down to avoid another overwhelming summer like this one. In any case this winter I’m planning to invest in some infrastructure, including new aircraft and a hangar. While these will directly support Fairbanks Fodar’s mission to map the State one 15 cm pixel at a time, it will also go to support our scientific mission to understand the impacts of climate change on the glaciers and ecology of the eastern Brooks Range, centered around the McCall Glacier study I have been leading since 2003. So I’ve arrived exactly where I hoped I would, albeit a few years late and not with the title I was expecting, having achieved the purest form of tenure possible — beholden to no one to pursue the science projects I believe are the most valuable use of the limited time we are all given to do something useful with our lives.

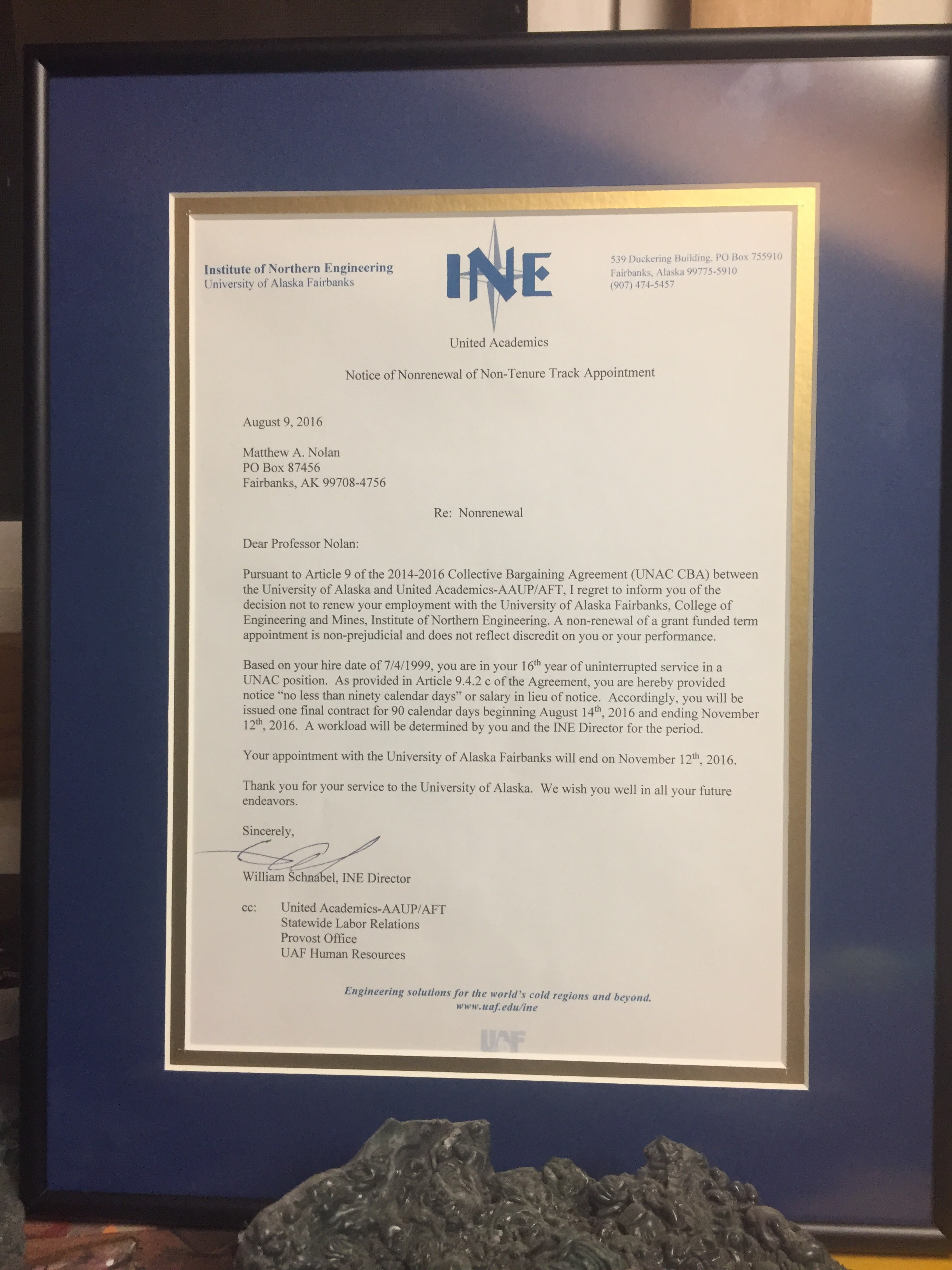

They have very high standards at the University of Alaska Fairbanks — apparently slackers like me just drag their reputation down…

They have very high standards at the University of Alaska Fairbanks — apparently slackers like me just drag their reputation down…

Or in other words, after taking my first summer off in 17 years to work independently, I realized that the only way to do my job was to quit my job.