How the West was Won

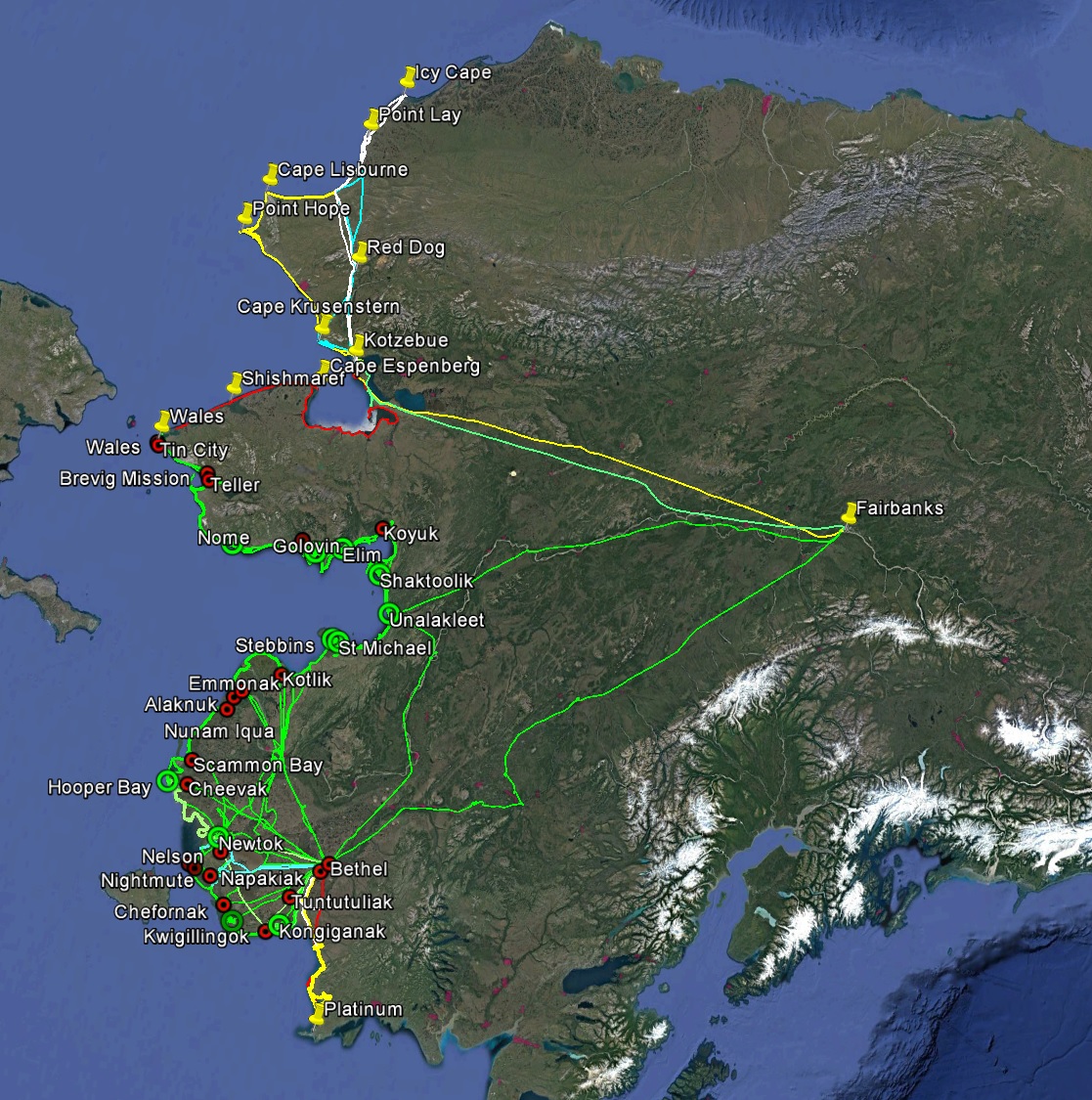

This week we completed acquisition of data for the entire west coastline of Alaska, mapping over 2000 miles of beach from Icy Cape in the north to Platinum in the south, a length longer than the east coast of the United States, at a resolution of 10-20 cm and a width of 1000-2000 m. This blog tells the tale of the final phase of that effort.

After completing acquisitions for about 1500 miles of coastal mapping last spring, we received an award from the USGS this summer to map another 200 miles of the northwest coast, from Point Hope to Icy Cape. Though there are lots of remote places in Alaska, this area definitely ranks up there. Almost 600 miles from Fairbanks, less than 1500 people live within 150 miles of this beach within three isolated villages. It’s not really on the way to anywhere, except from Russia, and thus the main landmarks along the beach are over-the-horizon radar sites for national defense. The weather here is also notoriously bad — in addition to coastal fog, this point of land jutting into ocean gets hit by weather from both the west and north. Kotzebue is the nearest town with fuel and lodging, a little over 150 miles away with about 3000 people.

I had organized several small projects in the area this summer such that I could base from Kotzebue and work in different directions from there based on wherever the weather was best. Unfortunately the weather has sucked there most of the summer. I did make it out here twice, once while mapping thaw slumps in the Noatak and once taking repeat oblique photos in the Noatak, but in both cases weather was moving in too quickly behind me to stay longer than to fuel up and leave again. I’ve been on heightened standby all of August but never had a weather window I could make use of. Finally in late August it appeared that a larger weather window was opening up and that the weather between Fairbanks and there was suitable too, so on Monday August 29th I headed out.

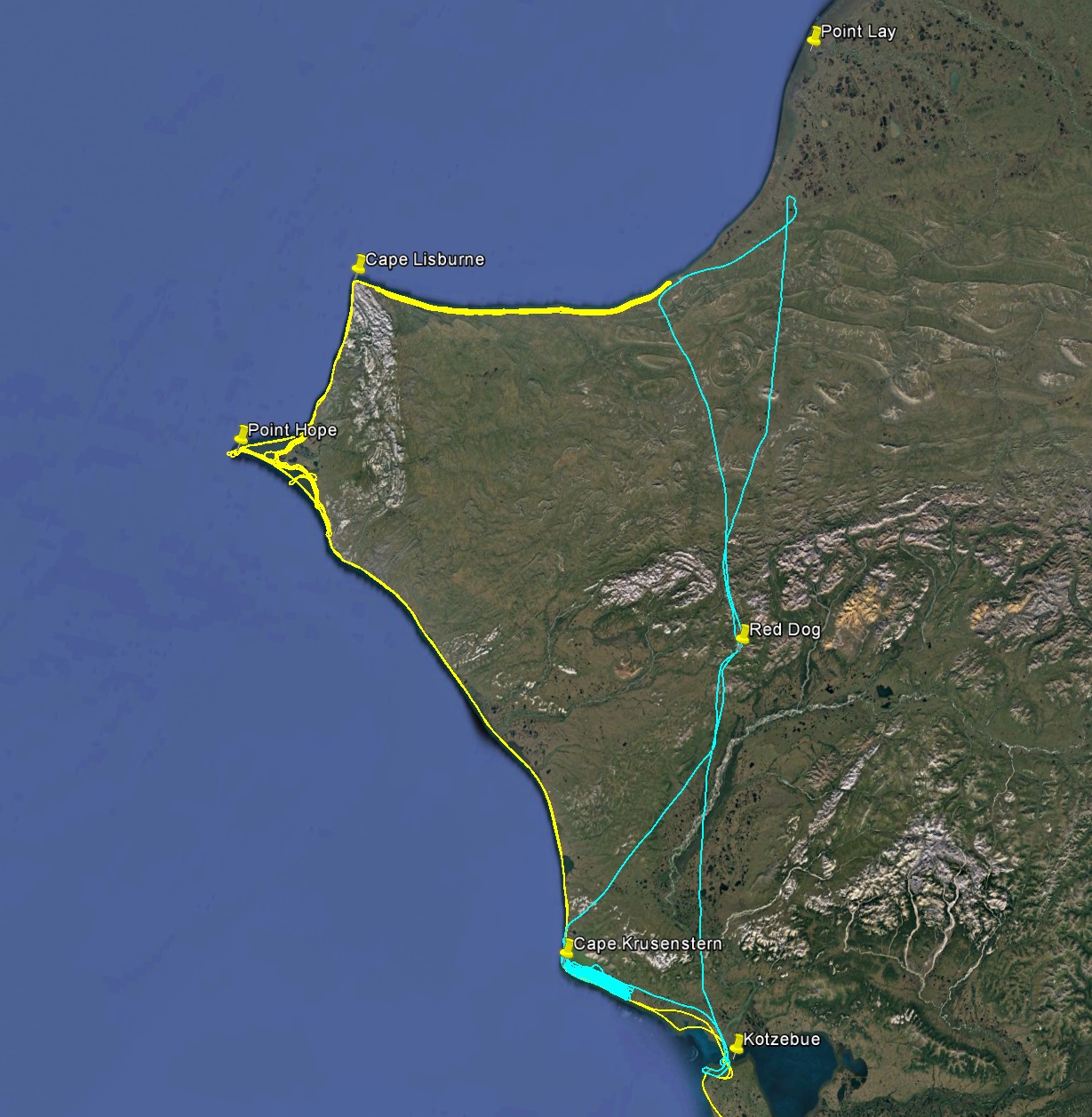

I mapped a mile-wide swath from Platinum to Wales last fall and this spring. On this trip I extended that up to Icy Cape, completing the entire west coast of Alaska.

29 August 2016

The previous week the forecast has been teasingly good several days out, but the actual weather disappointing. Finally yesterday it appeared as though I would catch a break. The costs of being on weather standby are difficult to appreciate unless you’ve been on it for weeks or months on end. It means not being able to make any plans, because you dont really know from one day to the next whether you’ll be in town for the next week. For example, I turned 50 this month, but was unable to organize a party because I had these projects still outstanding, and things like vacations or camping trips aren’t even a consideration. It also means not being able to take on large project elsewhere for fear of over commitment, as it often happens that the best weather windows cover the entire state at once. In any case, I had the plane prepped and ready for weeks, so with the weather looking good I was airborne by about 7 AM heading west.

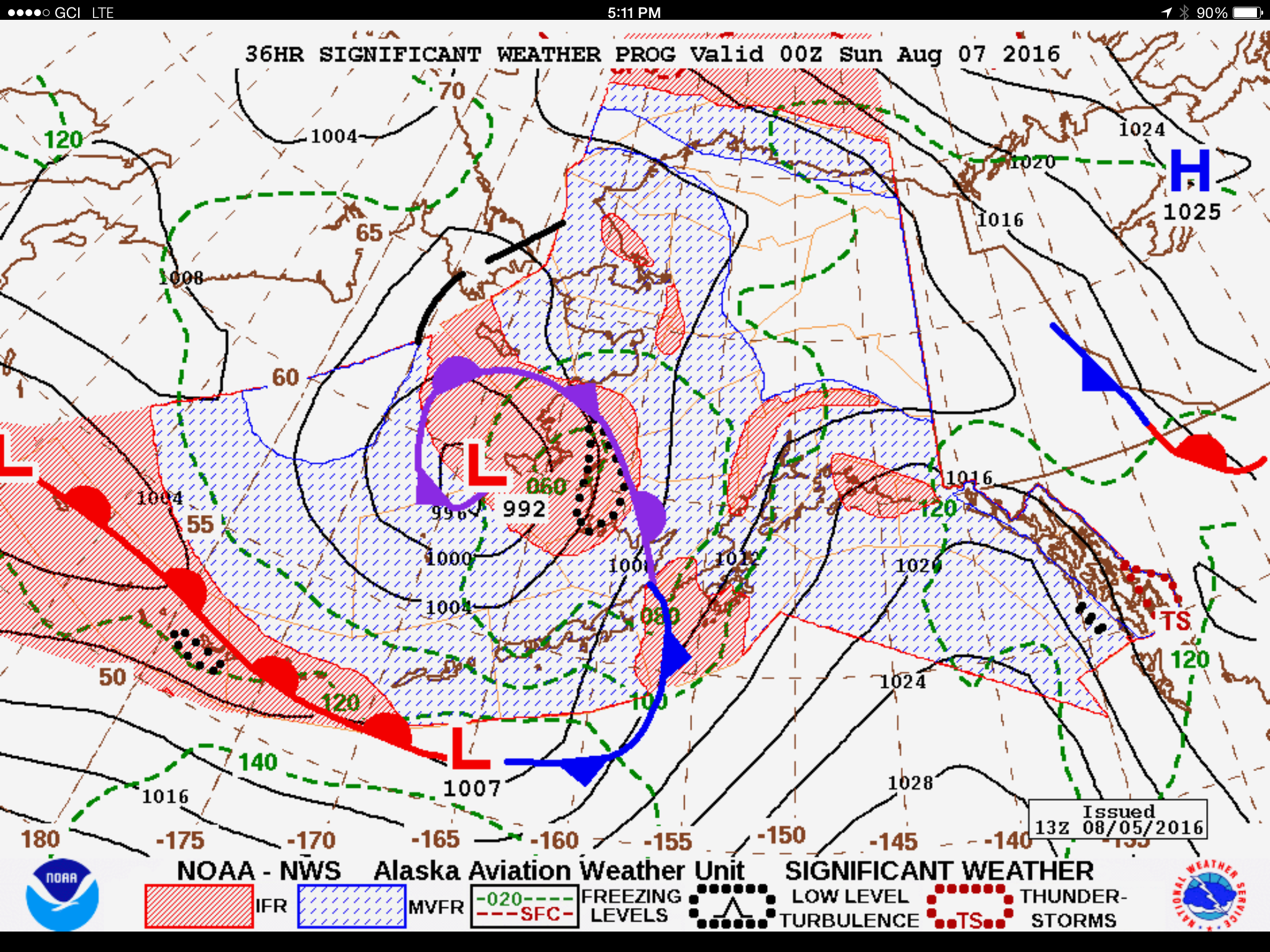

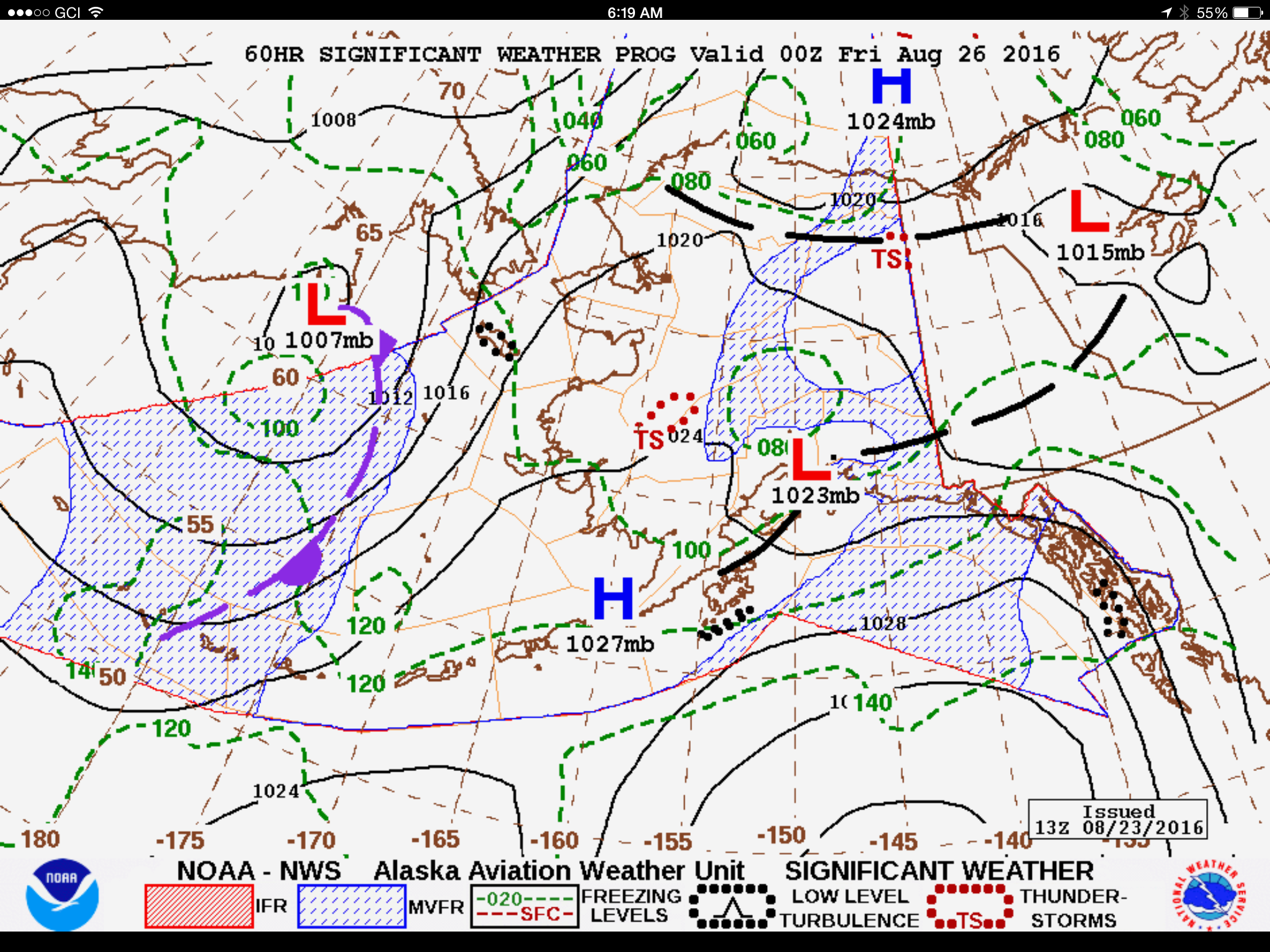

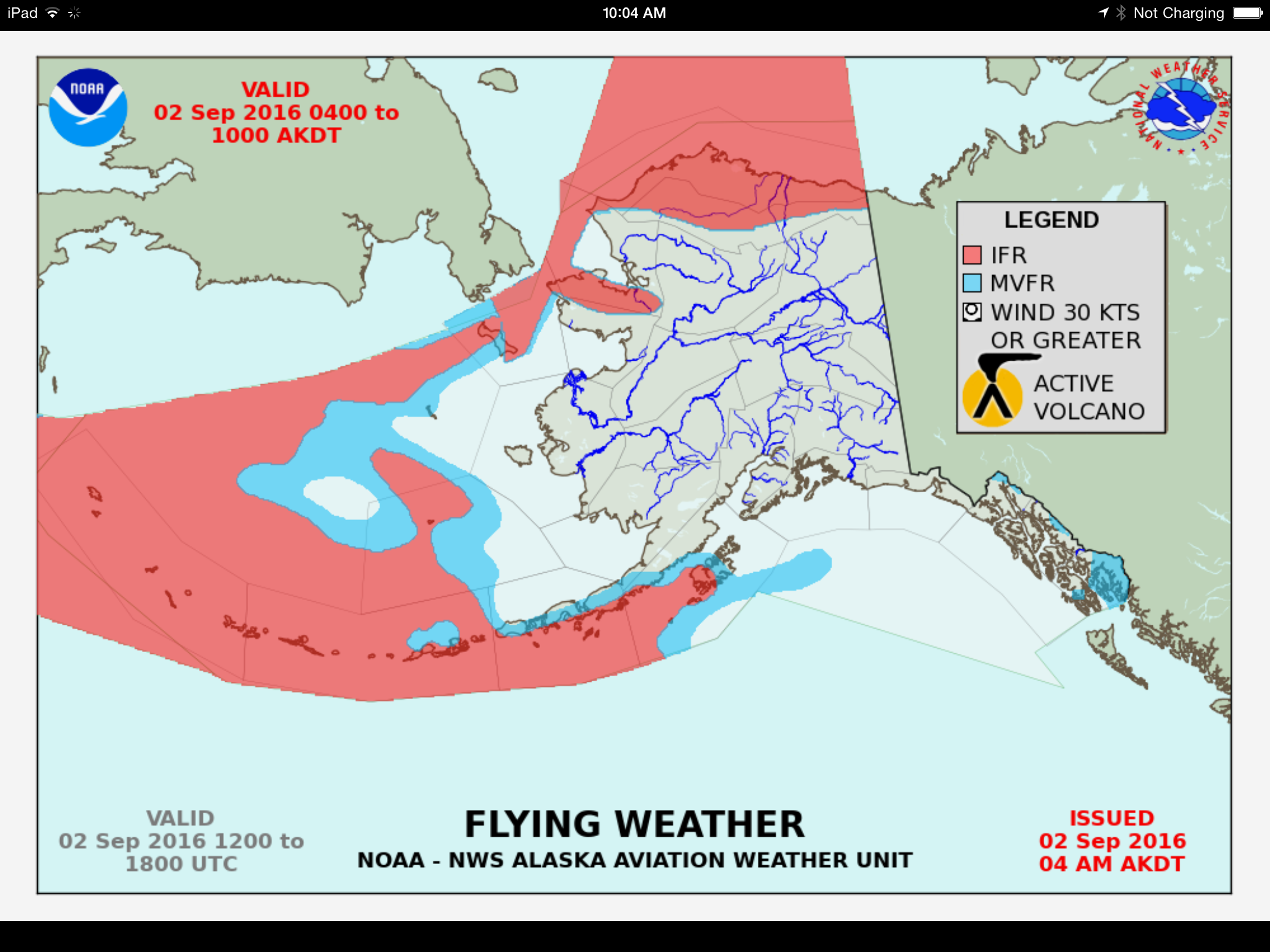

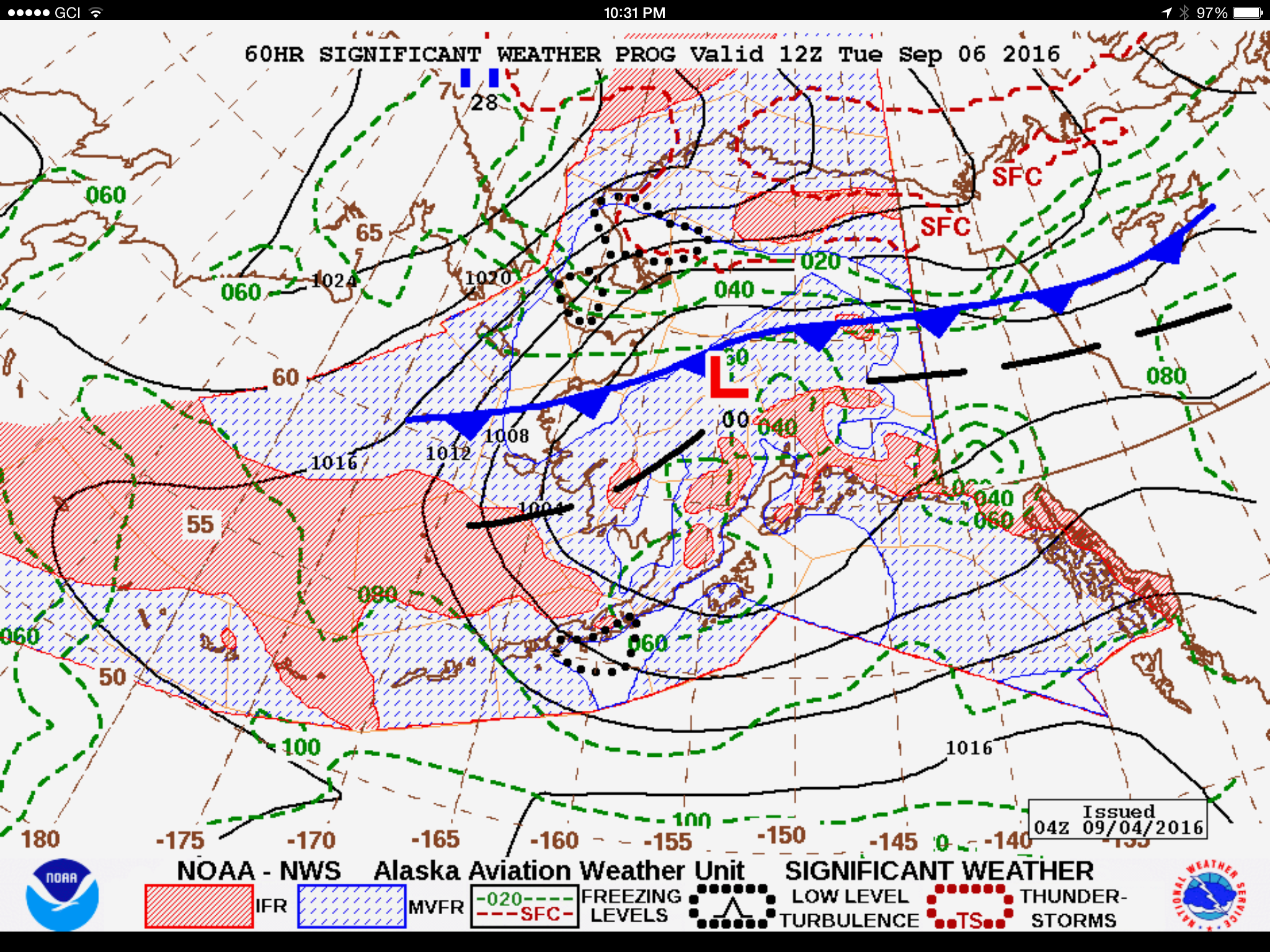

This is a bit of what being on weather standby is like — perseverating over weather forecasts like these. Giant low pressures like this one are typical in winter, but it seemed to me that they started a little early this year. Here blue shading means bad, red shading means really bad, and areas within the black dots mean hellacious. Compare this chart to the previous image to get a sense of where Point Hope and Icy Cape are. Note the issued date at lower right and forecast date at top. I was actually in Kotzebue the day before this forecast, which is why I left…

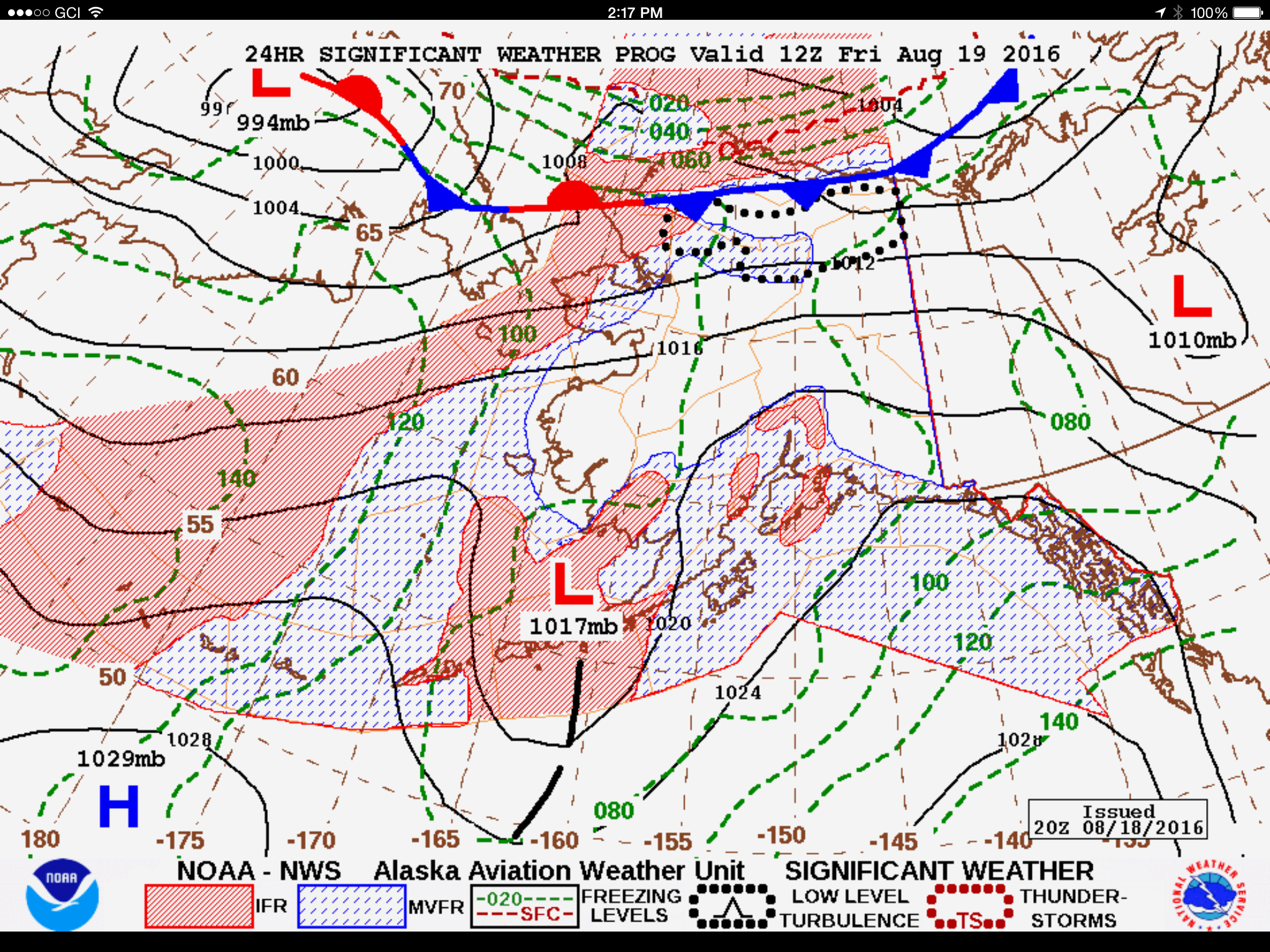

If it wasn’t low pressures from the Gulf it was vigorous cold fronts from the north, all month long.

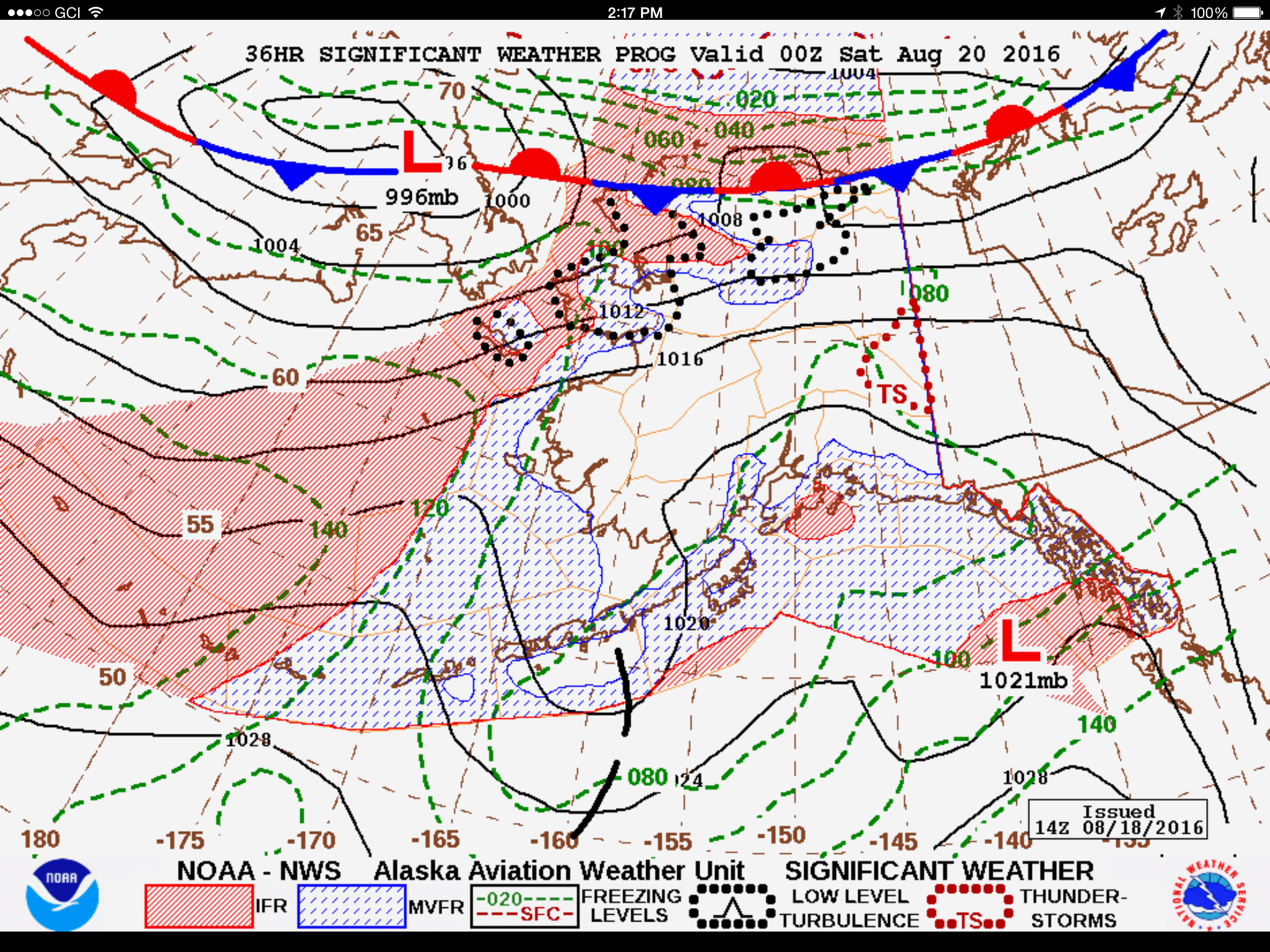

The high pressures and low pressures occasionally conspired to rip winds straight through the study area.

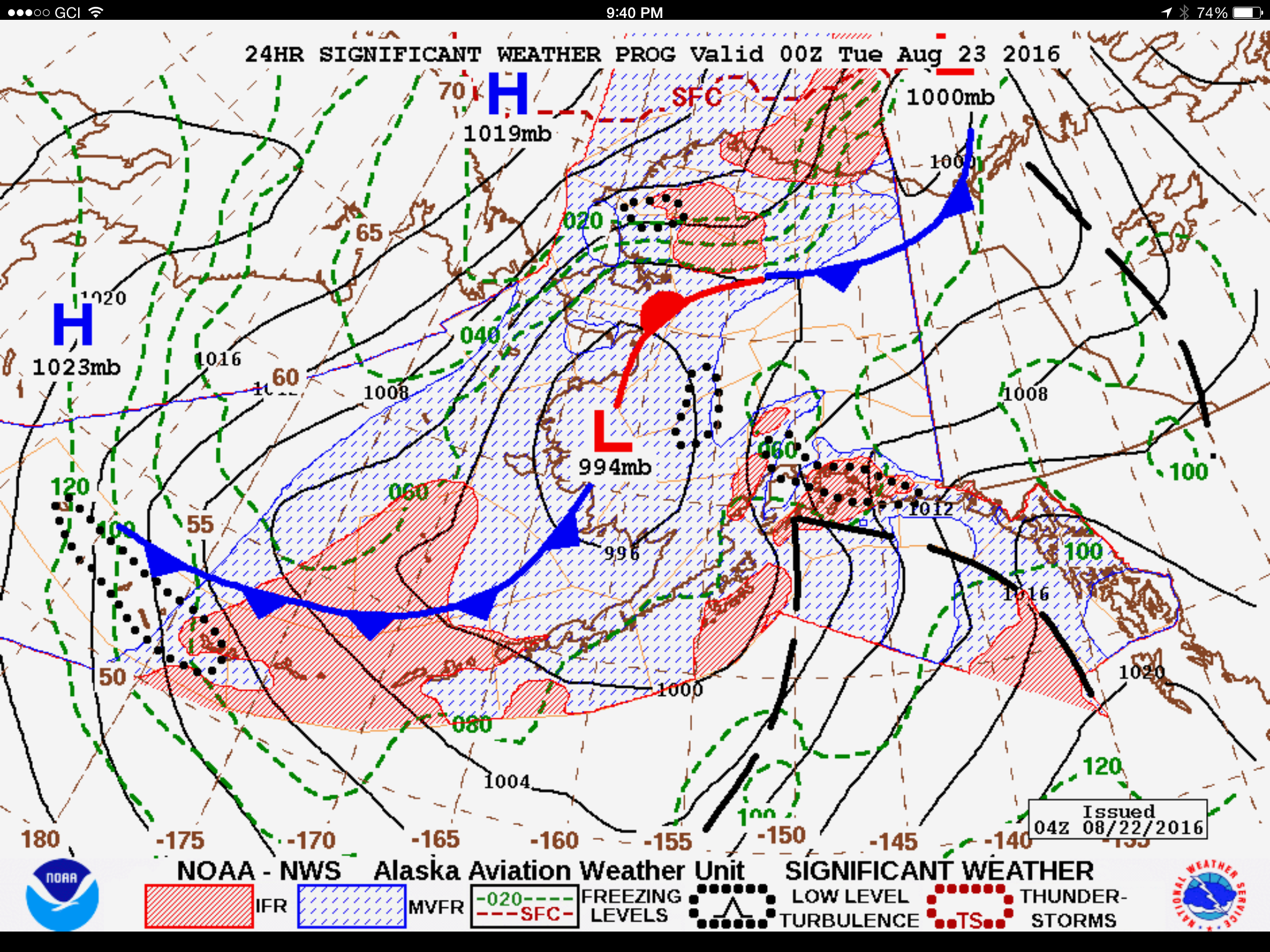

Occluded fronts with zonal flow filled in the gaps. This was just not the place to be this fall…

Finally the forecast began showing signs of improvement. This is 3 days out from August 23rd. It didnt materialize until 3 days after that. If looking at these forecast charts seems a little boring, imagine doing it several times per day for a month in realtime…

Daylight is getting noticeably shorter this time of year. In the peak of summer, I was up at 4AM checking weather cameras and trying to beat thunderstorms building up in early afternoon. Now it’s not bright enough to see anything on the cameras until 6AM and thunderstorms are much less a concern. Fortunately for the first time in a while I didn’t have to fight my way out of early morning scuz and ground fog in the Fairbanks area, and was able to beeline it straight to Kotzebue.

My plan was to fuel in Kotz and head directly to the site. It’s roughly a four hour flight for me from Fairbanks, and that put me in just after 11AM. Once fueled, I was in the air again before noon without a cloud in the sky and looking forward to finally knocking this project out.

I planned about 12-14 hours of mission flying to cover the stretch between Point Hope and Icy Cape, plus its a 3-4 hour round trip to commute there from Kotzebue, so I was thinking it would likely take a comfortable 3 days to complete given fuel and daylight considerations. As it was on the way, I mapped the coast from Kotzebue to Point Hope even though it was not part of the funded project, thinking someday someone would find it valuable. Along the way I also passed over and mapped the small village of Kivilina and the port of Red Dog mine, the world’s largest zinc mine. My goal today was to map all of the mountainous area on the west end of the project, thinking the weather there was the worst and most hazardous and getting it done while the weather was perfect would let me cleanup elsewhere when the weather was more marginal. Fortunately the forecast here was to stay good for at least one more day.

The weather was still nearly perfect by the time I reach Point Hope. The village itself is this anomalous square of development on a wide, flat spit, with both ends of the runway ending in ocean. It took quite a bit of time finishing this up as the idea was to capture not only the ocean beach, but the beach of the lagoons as well, making three beaches in total, so in most places it took 6 lines to cover. Once it was mostly done, I left the last line inland for my return trip, as I was eager to capture the mountainous area heading towards the radar site at Cape Lisburne and work my way as far east as I could before fuel became too much of an issue.

A few weeks ago when it appeared the weather everywhere was crap, I had a new transponder installed that allows me to see surrounding air traffic and get current weather for the surrounding airports. It’s really a fantastic device. Knowing that the weather is still clear where I’m heading back to allows me to push my fuel reserves a little bit more, and with my fuel computer directly measuring my fuel usage I can both economize usage and know exactly what my reserves are. For example, the fuel computer is hooked up to my GPS such that when I enter a waypoint into the GPS, such as Kotzebue, the fuel computer tells me how much fuel I will need to get there given my current burn rate as well as how much extra I have when I land. Because I’m not necessarily trying to travel fast, I can pull back on the throttle quite a bit and really lean the mixture so that I’m burning less than 6 mpg, stretching my range enormously. But there is of course a limit and even though the weather was nearly perfect I turned back at about the halfway point of the project. Though it was a long day already, had there been fuel available anywhere in the area I would happily have finished the entire project that night and camped on the beach. As it was I returned to Kotzebue about 8PM after a pretty long but successful day of flying, having mapped about 250 miles of coastline.

When I landed I texted Kristin that I had lost my dinner and was starving. She took that to mean that I had eaten dinner, but that it didnt agree with me. But I really did lose it, still not sure what happened to it [Update: a week later I still havent found it]. In any case, when I got to the hotel, I filled a small trash bag with gatorade, soda, microwave burritos, brownies meant to survive nuclear winter, egg mcmuffins, and the like from their lobby store, and proceeded to eat it all within about 20 minutes before passing out. Suffice to say that I lost my dinner twice this day.

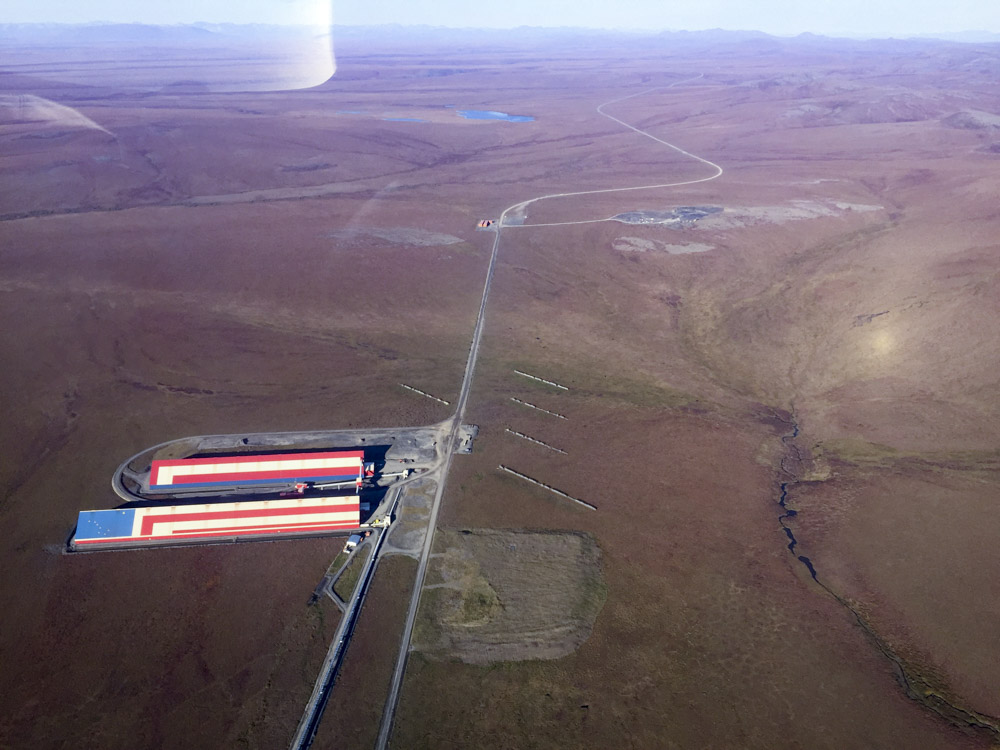

The road to Red Dog mine from the beach. I imagine it gets pretty miserable out here in winter, thus the large storage facilities for ore and equipment. The diagonal lines are snow fences to try to get the blowing snow to form drifts around the fences instead of the buildings. I guess the prevailing wind is from the upper right.

Point Hope. One of the tidier villages I’ve seen. Though that could be because anything that’s not nailed down gets blown away.

The local commuter pilots fly low and land at places like this like it was in Kansas.

I‘m a pussy over the ocean. I only need a few hundred feet to land, so I come in high and dive bomb down to land at the far end of the runway. I dont think I would make a good aircraft carrier pilot… That’s Point Lay in the distance, I made it about halfway around that curve today.

The runway at the Cape Lisburne radar facility. Note the giant golf ball on the peak in the distance.

You really can see Russia from their house.

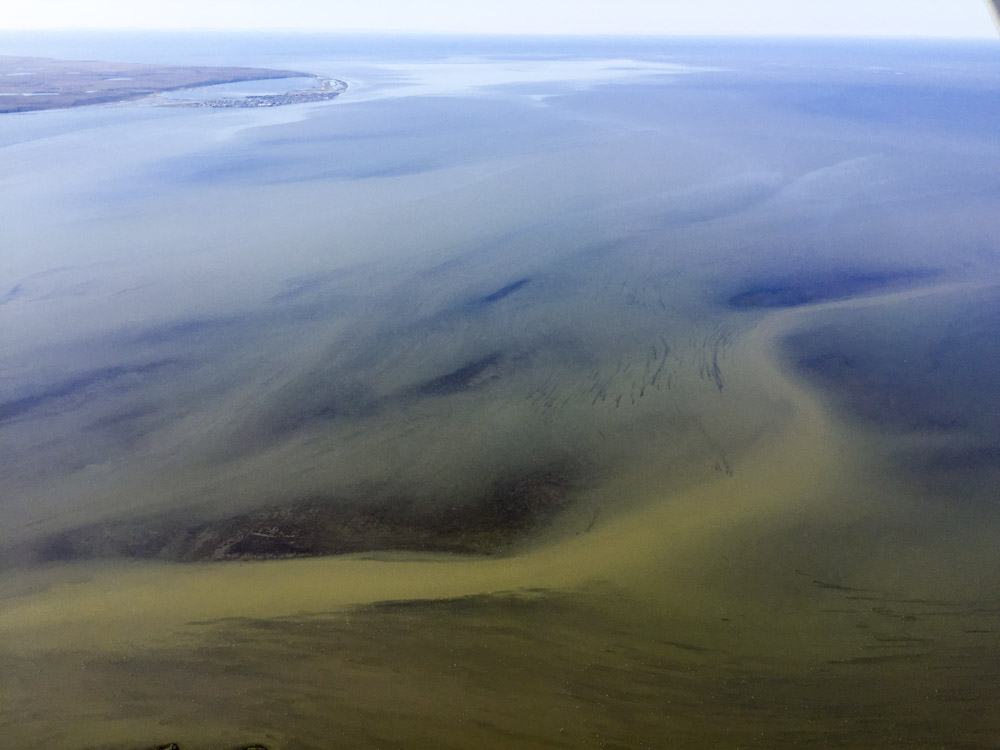

That’s Kotzebue in the distance. What I found interesting here were the linear features in the water. At the end of each one is a bird. This bit of water has to be crossed, else it means a 100 mile detour, but it’s only a mile or two wide, and obviously not very deep for most of it.

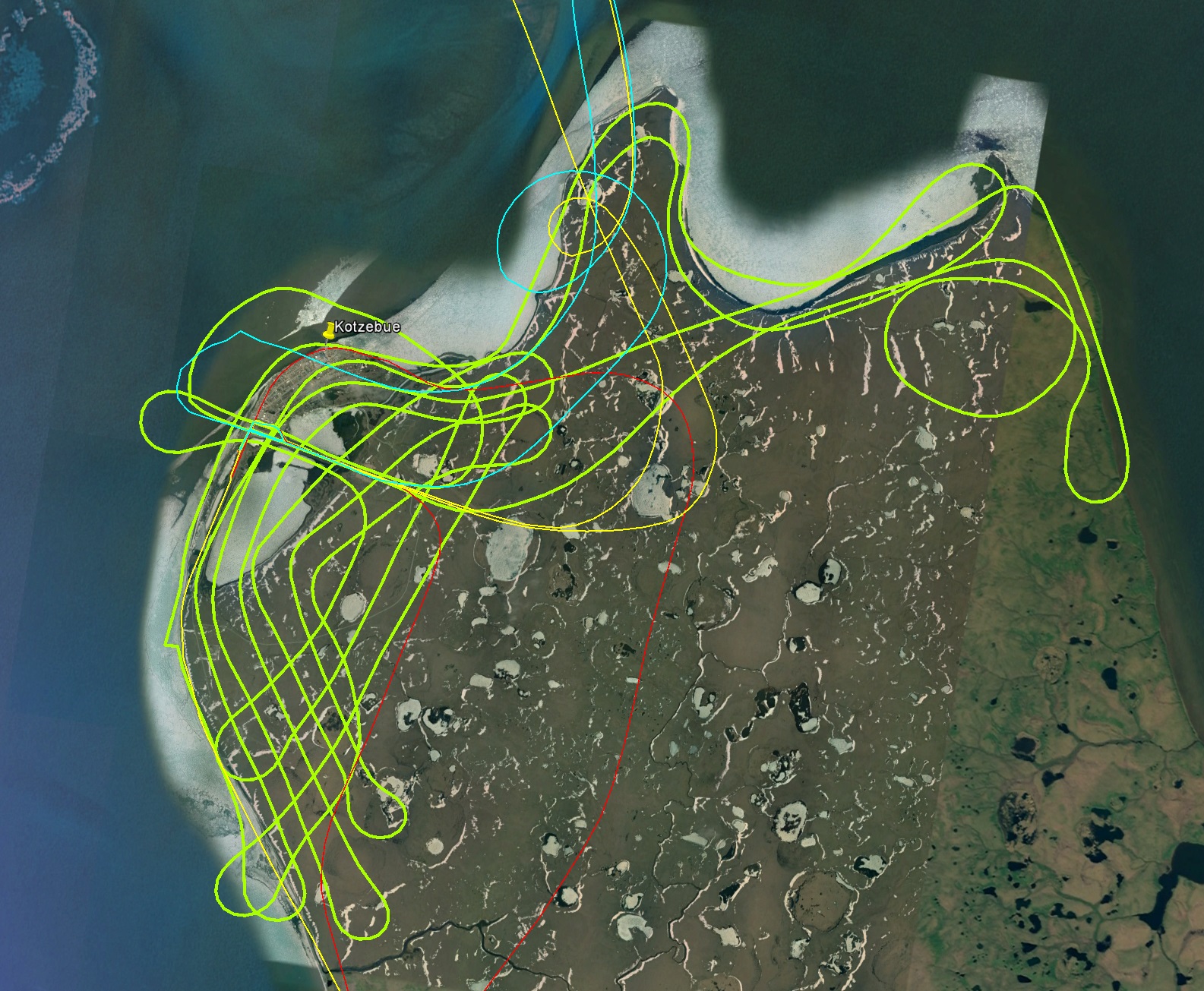

A busy but productive day. Most of the area got 4-6 lines, extending over a mile back from the coast. To save fuel I only acquired 2 lines over the steep, rocky beach as the primary objective here is to capture baselines for low-lying coastline change.

The port at Red Dog.

Ice rich coastal bluff becoming spit fodder.

30 August 2016

This morning’s weather checks showed that the good weather was continuing to hold, so I was at the plane about 7:30 AM prepping and packing. Here there is no self-serve fuel pump, so I have to wait for a truck to come and they dont open until 8AM. Unfortunately there was some issue with their phone, so it took a bit longer to flag them down, but by 9AM or so I was headed off. This time I cut inland over the mountains to save time to pick up where I had finished off last night. Along the way I flew over and mapped the village of Noatak and the mine site of Red Dog. There is quite the infrastructure set up around the mine. They have a full length paved runway, a huge number of buildings, and mining pits everywhere. I dont know much about the operation, but they clearly run a small city there to support operations as well as their own road to the ocean and their own dock, presumably with trucks hauling ore to the large holding buildings where it eventually gets loaded onto the large ships parked off shore. All in all it looks like a pretty tidy and well run operation, but I can only imagine their daily operating expenses must cost a large fortune.

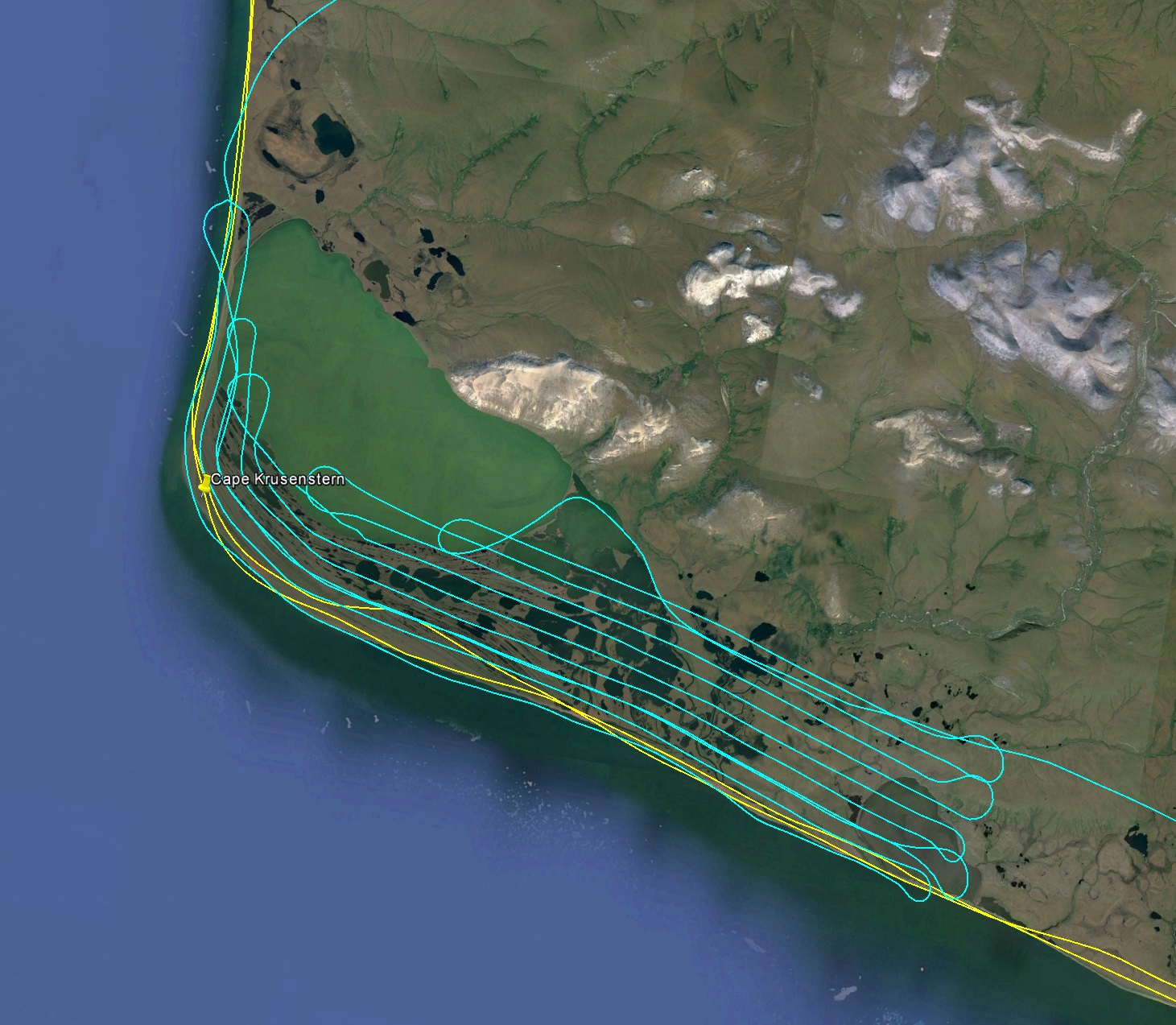

Unfortunately after I passed over the mine I discovered that the only weather reporting site within the remaining area was no longer calling for clear skies, but for thick fog. Indeed as I got onto the coastal plain I could see that the ocean was completely covered by fog and as I got closer it became clear that this extend a mile or two inland. Compounding this was the wind coming from the ocean, pushing the fog towards land. Everywhere else for hundreds of miles was clear and sunny, except this narrow strip of land that I was interested in! I cruised up for a while, idly mapping fog heights and checking out the geological structures making swirls within the fog, but before long it became clear that the entire stretch of interest was covered and getting worse as I went north. Cape Lisburne and Point Hope were also now under the same fog, so with no place local to land and wait and no signs of improvement, I had little choice but to head south back to Kotzebue. With plenty of fuel and good weather, I mapped more of Red Dog on the way back, as well as Cape Krusenstern.

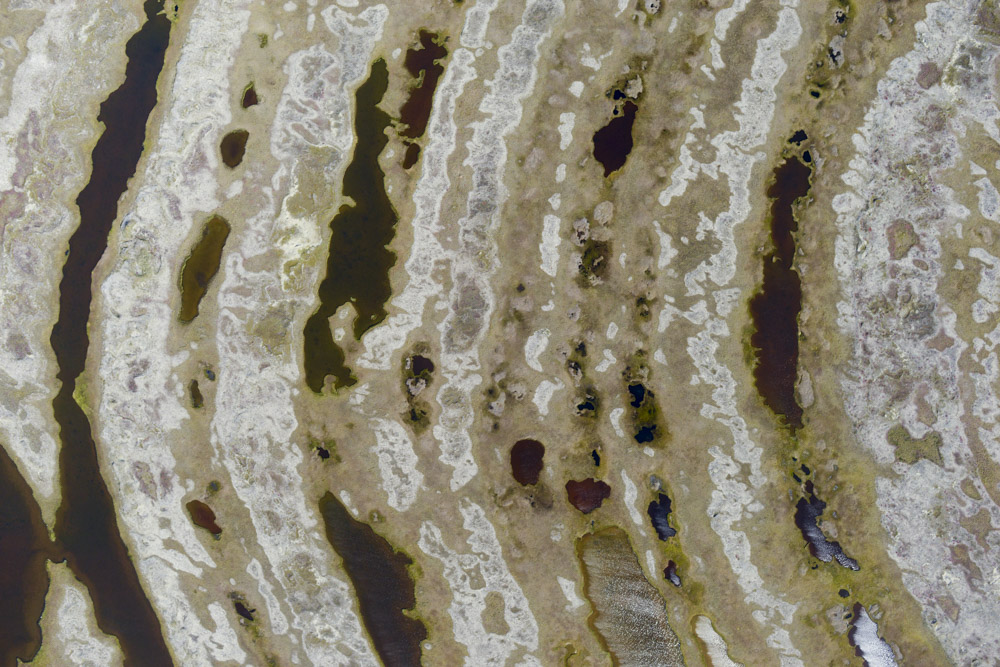

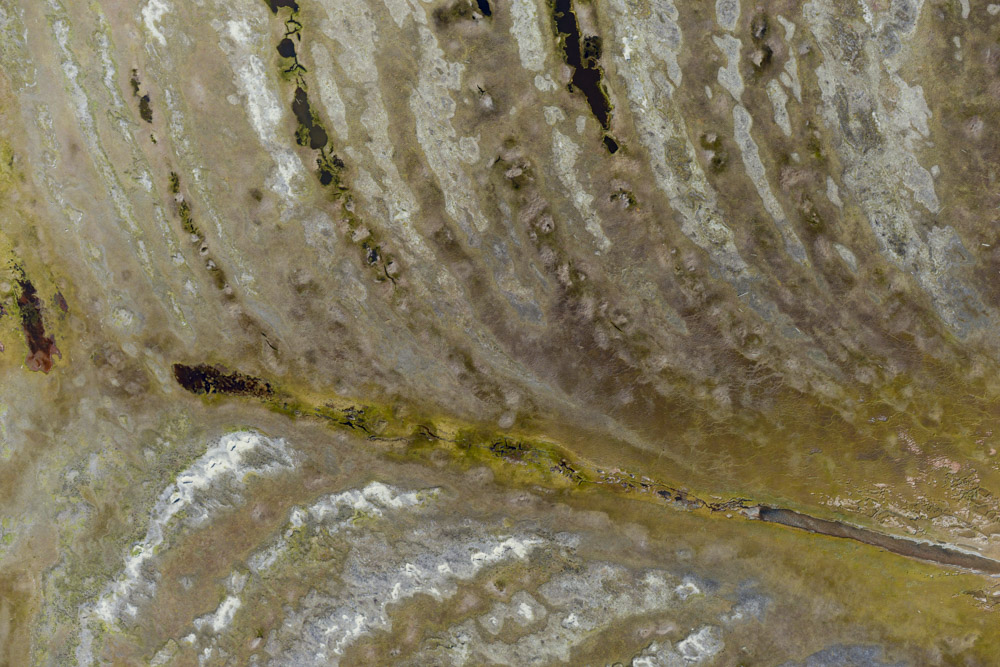

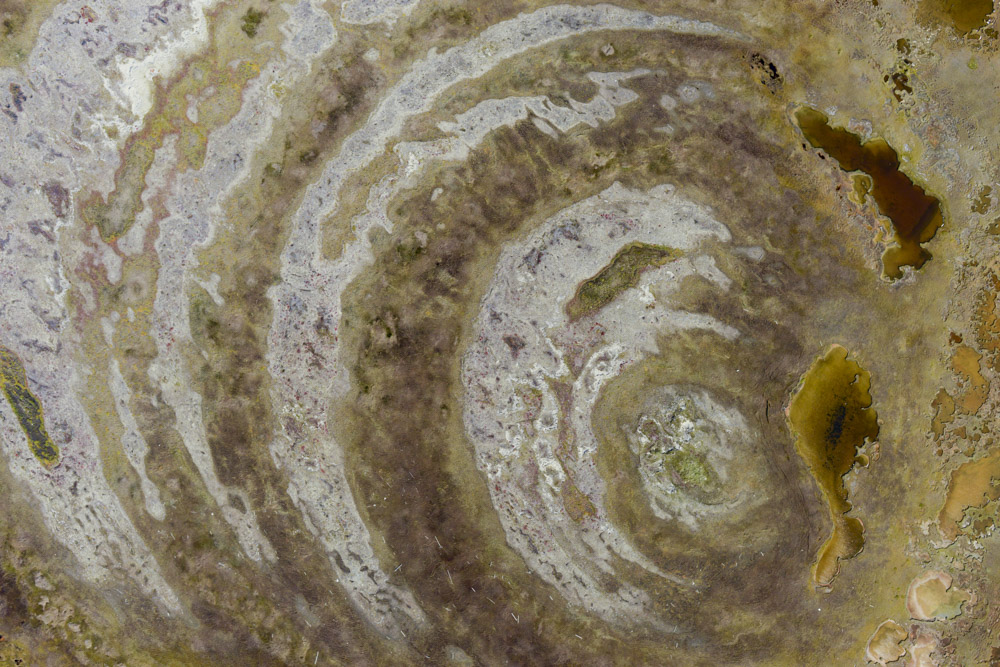

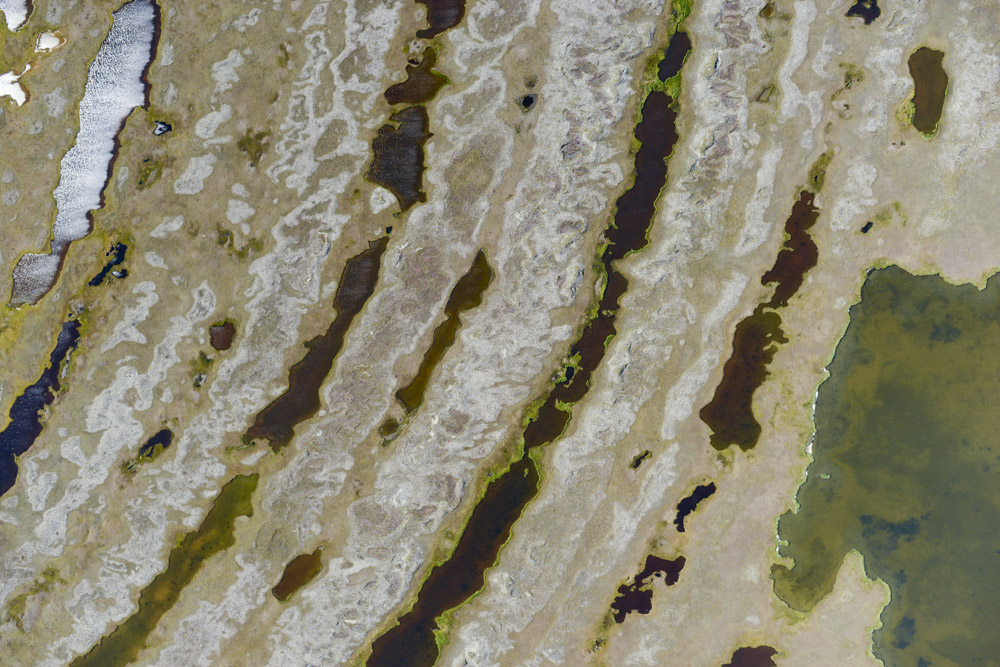

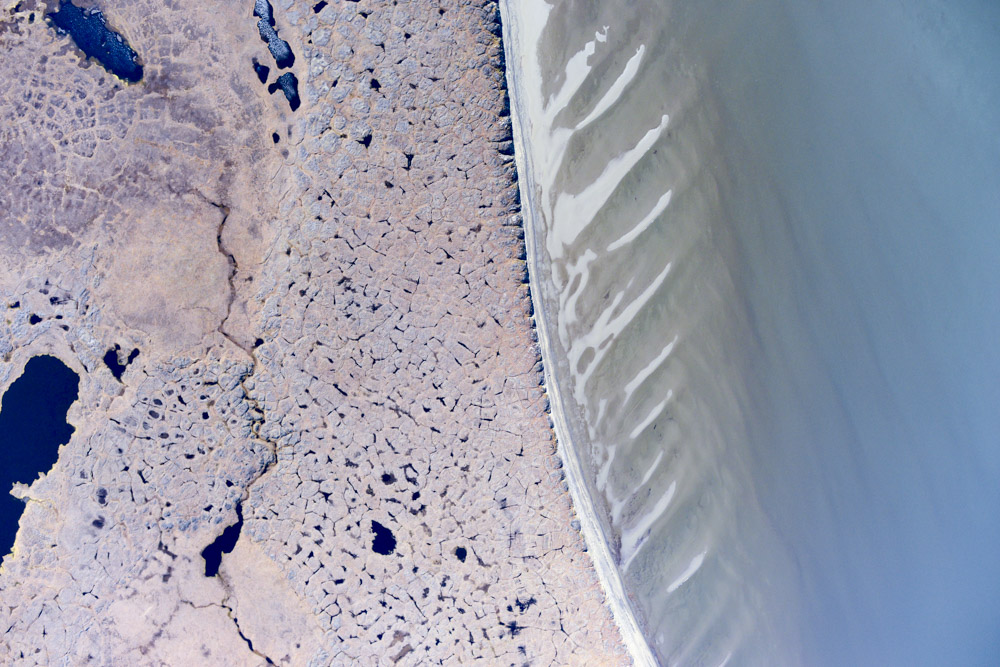

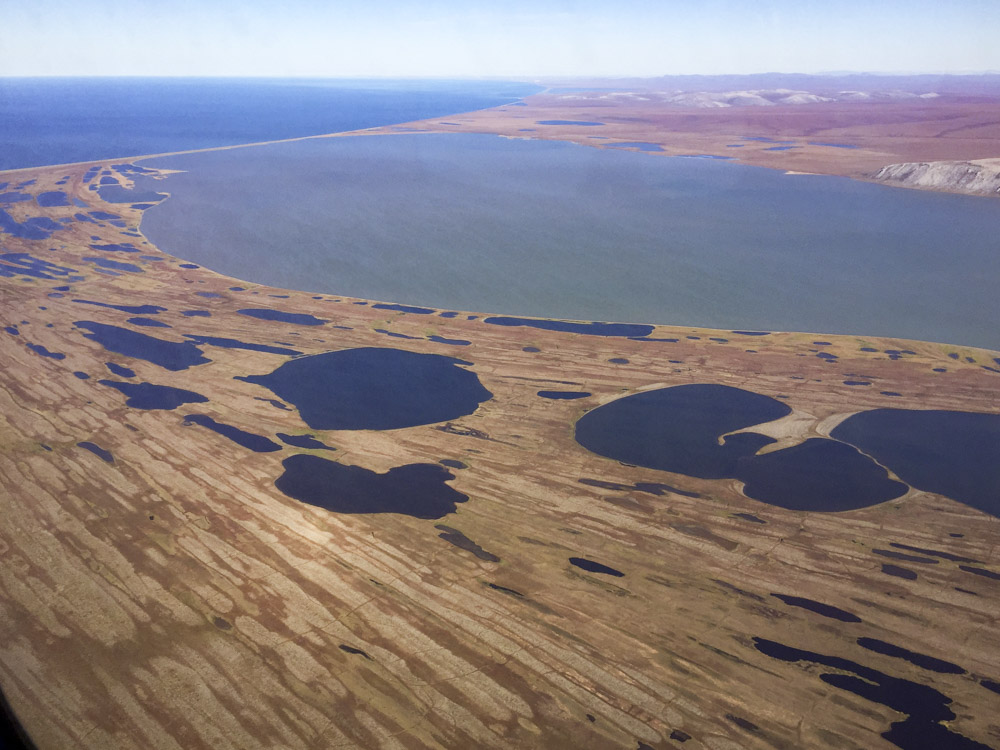

Cape Krusenstern is a neat looking place. It is a series of low ridges, with each ridge being an old beach, such that the oldest ridges are furthest back from the current beach where the latest ridge is presumably being formed. Besides being cool to look at from the air, ancient man apparently thought they were cool to look out from on the ground and spent a lot of time around here living and hunting from the beach, continually moving their operations oceanward as each new ridge was formed, creating for us a time-series of archaeology dating back over 5000 years, spanning 5 cultural periods on the 100+ old beach ridges. The area is now protecting as part of one of four National Parks in the Arctic. That’s about the extent of my knowledge about the site, but given the state of things I figured someone would probably like to have a nice map of the area, so I made one. It was a beautiful afternoon, with a beautiful view, and it gave me the chance to see just how little fuel I could burn and still stay airborne, so all in all not a bad consolation prize.

Once finished with the cape, I landed back at Kotzebue to refuel. I had been keeping my eye on the weather at Point Lay, but it never improved. Worse, the forecast was not showing signs of improvement for the foreseeable future. Except for that 1 mile strip of beach, the forecast everywhere else was for clear, calm skies, so I figured I would simply wait here until weather forced me out and hope for the best. In meantime, I would try to make myself useful.

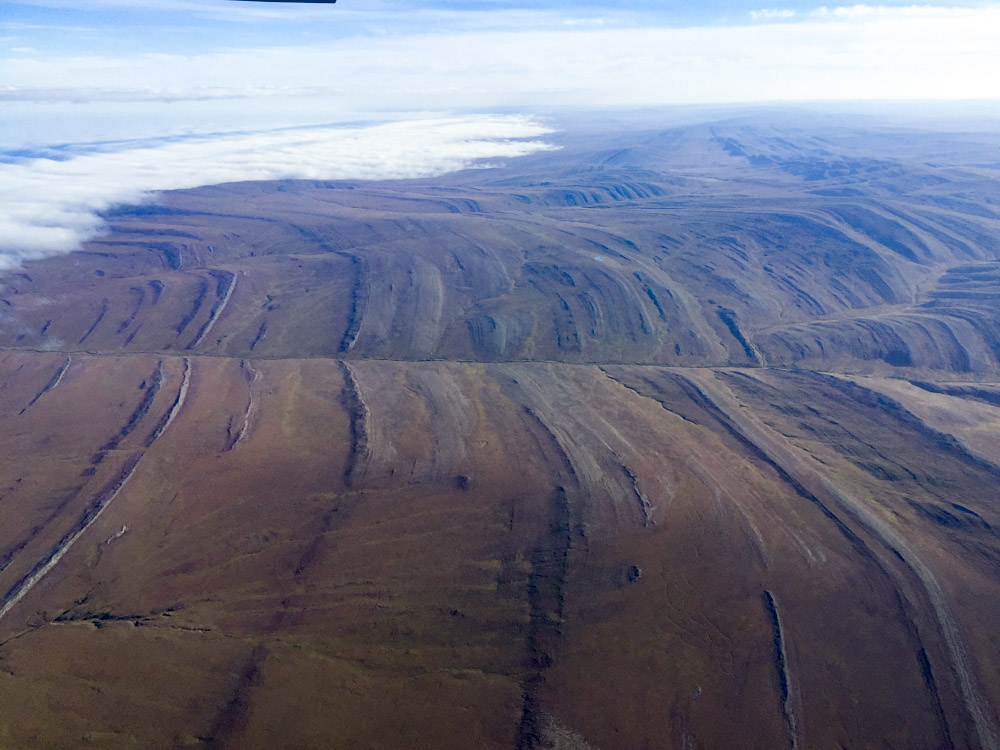

It was a pretty day in the mountains. Looks kind of white in the distance though.

They run a small city here. Well, a large city by Alaskan standards.

I was excited to possibly finish the main project today, but the coast was socked in solid. Today’s lines are in blue.

Weeping Angel wasn’t very happy about this fog. It extended all the way to Barrow apparently.

The ocean is on the right and the wind was blowing towards shore. There wasn’t much hope of this clearing any time soon.

I spent some time mapping fog heights, just because I could, but it seemed like there was more productive things I could be doing so I headed south.

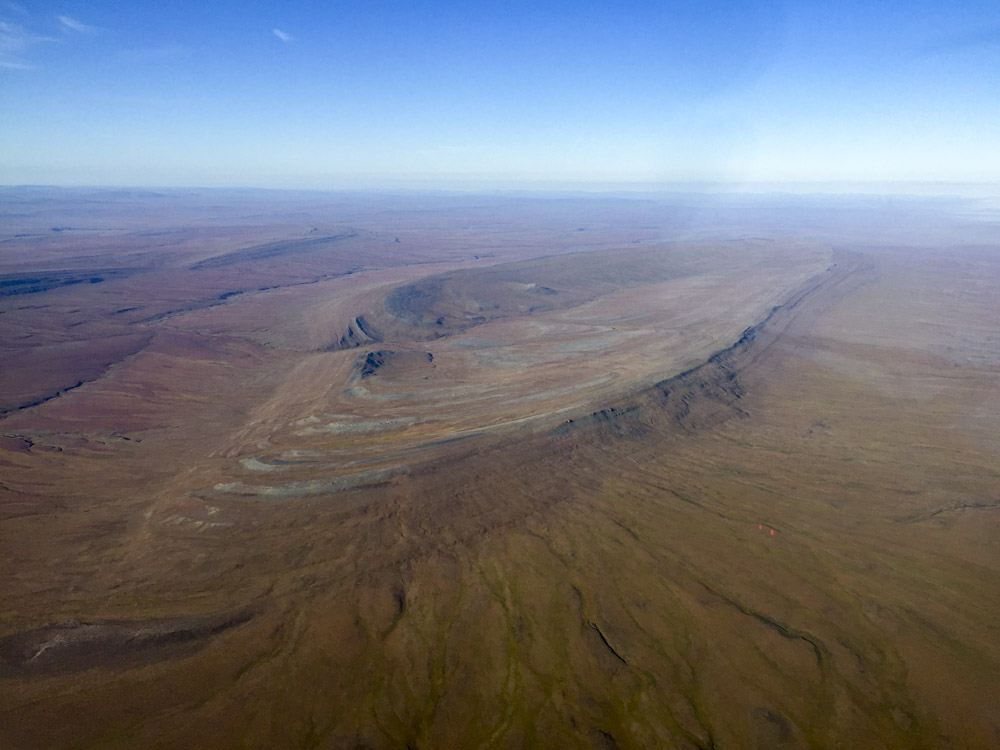

Really neat geological structures around here. grading into the ocean in places.

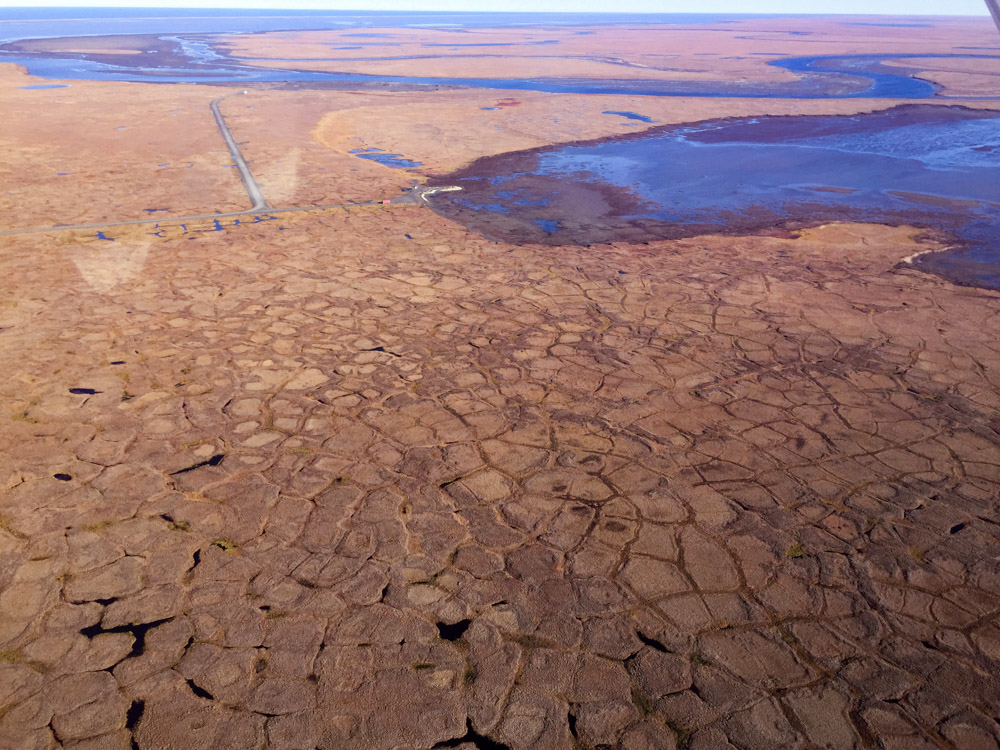

I imagine things that look like this must be buried beneath Prudhoe Bay.

Cape Krusenstern. It’s a neat area with 5000 year old beaches. It looks a bit like the lake there is gradually consuming the area. Someone should make a time-series of maps here to find out…

Cape Krusenstern, looking north towards that big lake. Each of those stripes is an old beach, and each old beach is littered with debris from ancient man. You can see how the prevailing currents changed over time creating uncomformities. Those uncomformities were the Shishmaref of their era, though I imagine it cost a lot less to move a village back then…

An uncomformity, presumably caused by a change in currents.

It’s almost like tree rings. I wonder if the width of the beaches says something about the climate they formed in?

The patterns of nature are too bizarre to be predicted. Only observations can drive modeling.

31 August 2016

As predicted, the Point Lay area weather and its forecast did not improve, so I went for Plan B. Plan B consisted of mapping Cape Espenberg and Shaktoolik, as well as the remaining beach between Kotzebue and Wales, completing my acquisitions of the entire west coast of Alaska, I guess in the short term for bragging rights but hopefully in the long-term because someone will find it valuable enough to purchase. I guess in the end I’m not sure what’s really considered the ‘west coast’ in Alaska, as its not nearly so clear cut as in the states. I figure it is the west facing land from Cape Lisburne to Platinum. Partly that’s because that’s what I have mapped, but more importantly if you look at the shape of the land that looks about right. One could also argue the west coast could extend from Barrow to the Aleutians, but I think that’s taking it too far, as in that case there would be nothing left to call a north or south coast. In any case, it’s a hell of a lot of the west coast at worst and all of it at best.

The funny thing about measuring coastal distances is that the length you measure depends on the size of your ruler. That is, moving at 50 meters per second in an airplane gives you a different number than if you were walking along the beach measuring with a yardstick, because with the yardstick you can measure more crenelations, like the scarps of individual wave cuts, and this difference can yield a 5-100 x difference in length even when using much larger rulers (eg, like here). So I really dont know how long the beach is that I’m measuring, but I use a ruler that is about 50 meters long. When I apply that to the distance from Platinum to Cape Lisburne, I get a number that’s more than 2000 miles.

The trip down the peninsula and across to Cape Espenberg was a pleasant one. Between the decent headwind and more crenelations than I imagined, it took a bit longer than I had planned, but the weather was holding so I was optimistic. Up until Cape Espenberg, I was mapping at 17 cm ground resolution, at which point I lowered down to map at 10 cm. Cape Espenberg is another one of those aggrading beaches with a time-series of archeological ridges, so it seems like a bit higher resolution might come in handy for someone. I had mapped it 3 years ago (to the day!), after finishing my first real mapping project shortly after getting my commercial pilot licence at a location just inland near the Serpentine River. That project was laying down some baseline measurements for the National Park Service to detect future change. So with a bit of extra fuel after finishing that work, I thought it would be neat to map the coast here for similar purposes. Now here I was again at the edge of nowhere, mapping changes to my own baselines exactly three years later.

Whether its ironic or just physics, apparently at least some of the material being used to build new beach at Cape Espenberg is coming from out in front of the village of Shishmaref. Shishmaref has been in the news a lot in the past 20 years because every storm seems to take a piece of it out to sea. Some of the buildings are now literally jutting into the surf with enormous breakwaters and earthworks attempting to keep erosion at bay. But even a glaciologist turned pilot can see that this is a losing battle and if the powers that be keep this up, it wont be long before the beach disappears completely and the village of Shishmaref becomes an armored island in the ocean. What I found really odd though was that they just repaved the runway. For such a remote area, this was a huge undertaking. I remember landing here several years ago and noting that the runway surface was definitely on the rough side, but now seems like the time to be spending money on a runway for a new village site. But perhaps a decent runway is needed to get bigger cargo planes in for a major relocation. In any case, its a beautiful surface right now. In fact a bit too beautiful — they are still actively working on it and after I landed all worked stopped and everyone just stared at me while I fueled. I double checked the notams and it said the airport was only closed at night, but it still felt a little creepy. In any case, I fueled as quickly as I could and took off again, into the 15 knot direct crosswind across this brand new runway…

The decision I had to make at that point was whether to continue down the coast to Wales or not, about 50 miles away. I had already burned more fuel than I had planned coming in, and was now not entirely convinced that I had enough to make it to Unalakleet for fuel so that I could map Shaktoolik. Plus there was daylight to consider as well. Wales had been IFR all morning, but when I checked now it was calling clear, so I took that as a sign that I should head that way and link North with South. That is, Wales was the northern-most point on my big DNR project this past year that extended down to Platinum, so by reaching there today from the north I would form a continuous measurement to Cape Lisburne. So I went for it.

As it turns out, I should have been there 30 minutes earlier. As I approached, as far as I could see a low fog extended over the ocean and was pushing in towards the coast. I couldn’t remember exactly where I stopped in Wales when coming from the south, but I know I was within 10 miles of it by the time the fog covered the beach. When I turned around, I discovered that it had also moved in behind me, so another 10-15 miles of my return towards Shishmaref was now covered. Over the land to the south, I could see there was a haze developing and I began to get concerned that the whole peninsula was about to pass a dewpoint threshold and go under. So at that point I gave up on Unalakleet and focused on the beaches here before further deterioration occurred, which fortunately it did not. After mapping Shishmaref completely at 10 cm, I made another 3 passes between there the end of the Cape. In retrospect, it might have been better to be a little higher and a little coarser resolution so as to have captured a bit further inland, but on the other hand that part of it isn’t going anywhere so I can always come back, preferably with someone else paying the bills next time. Though I wish there were more glaciers around here, ultimately that’s why I built this system, bought a plane, learned to fly, etc — so that I can map whatever I feel like mapping without having to convince someone else why I should beforehand.

Once finished with Cape Espenberg, I followed the coast again to complete the shoreline mapping all the way to Kotzebue. The trip was uneventful in terms of flying, but quite the event in terms of significance. By reaching Wales, I had now completed the largest airborne coastal topographic mapping project in Alaska in the past 60 years. Well, I had already done that several times, so I was now just beating my own records, but I guess the difference this time being that I completed an entire side to the State. And not just any State, but the State with the most coastline of any of the 50. Now all I had to do was add another 75 miles to it to finish the funded project that brought me out here.

Another beautiful day in the neighborhood. Unfortunately not so much in the next neighborhood over.

Today’s tracks in red. That’s about a 1000 miles of flying and a pretty long day, flying a lot of it at 70-80 mph in the headwinds.

The cape is continuing to grow, apparently using pieces of Shishmaref.

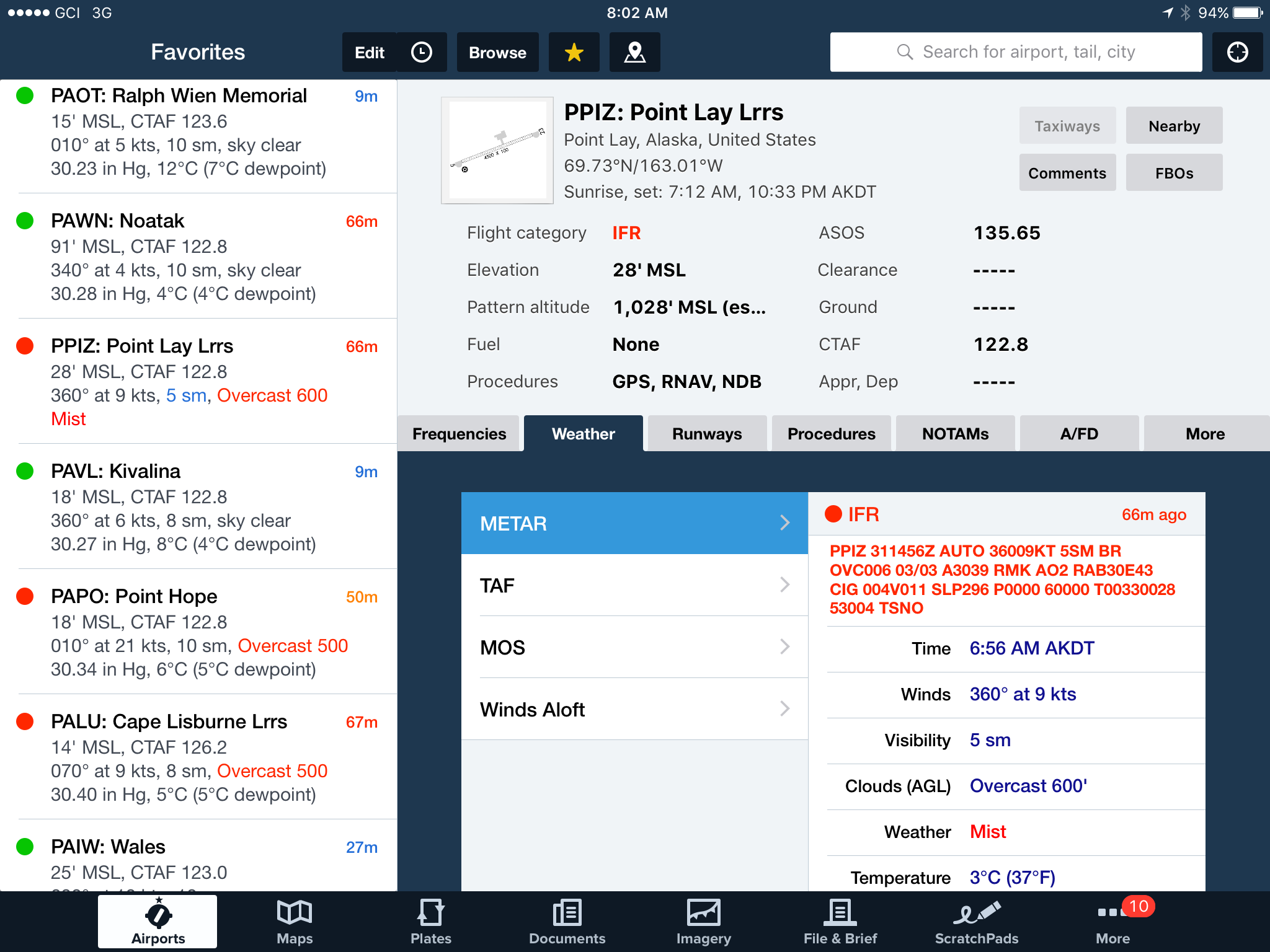

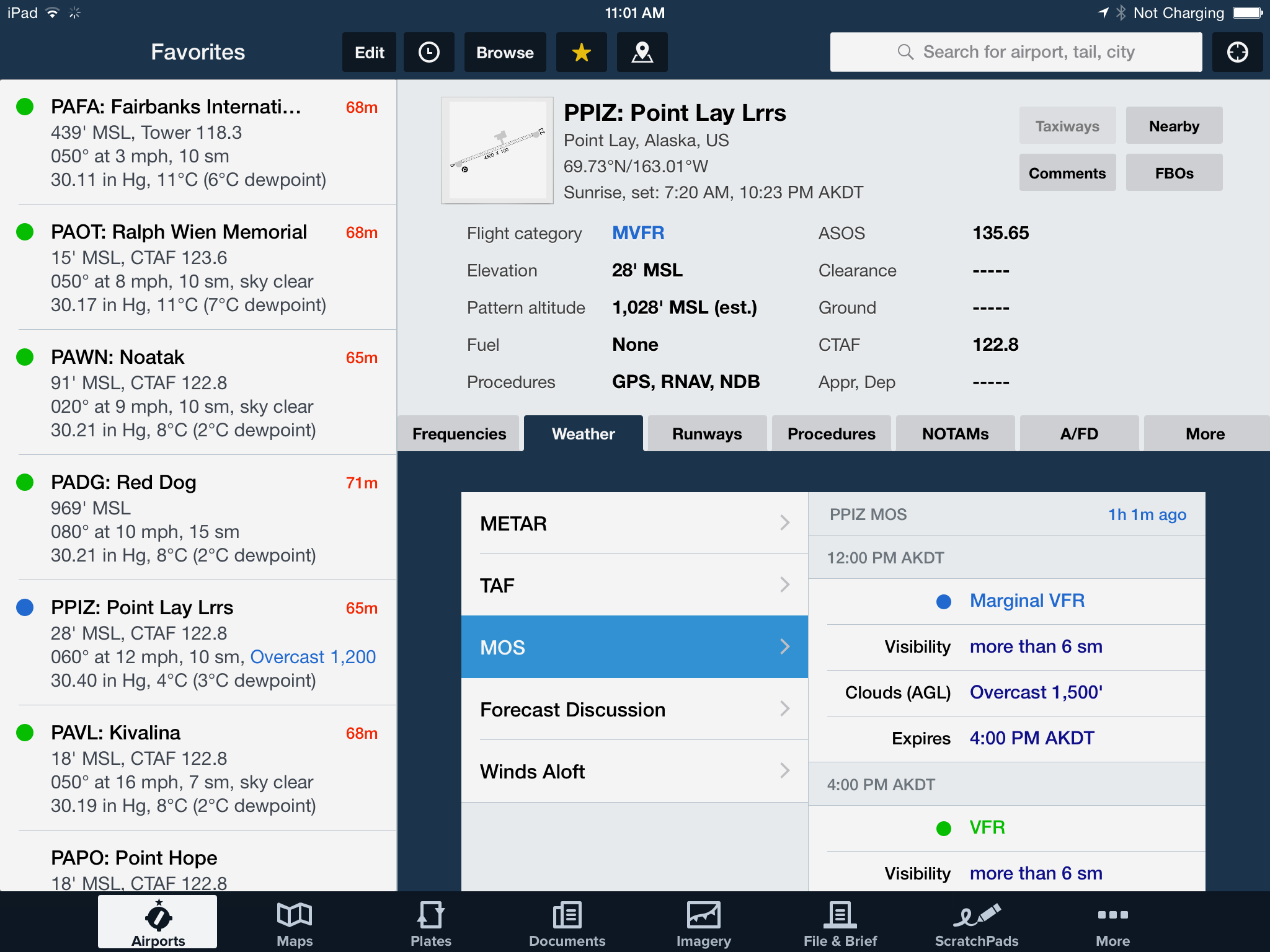

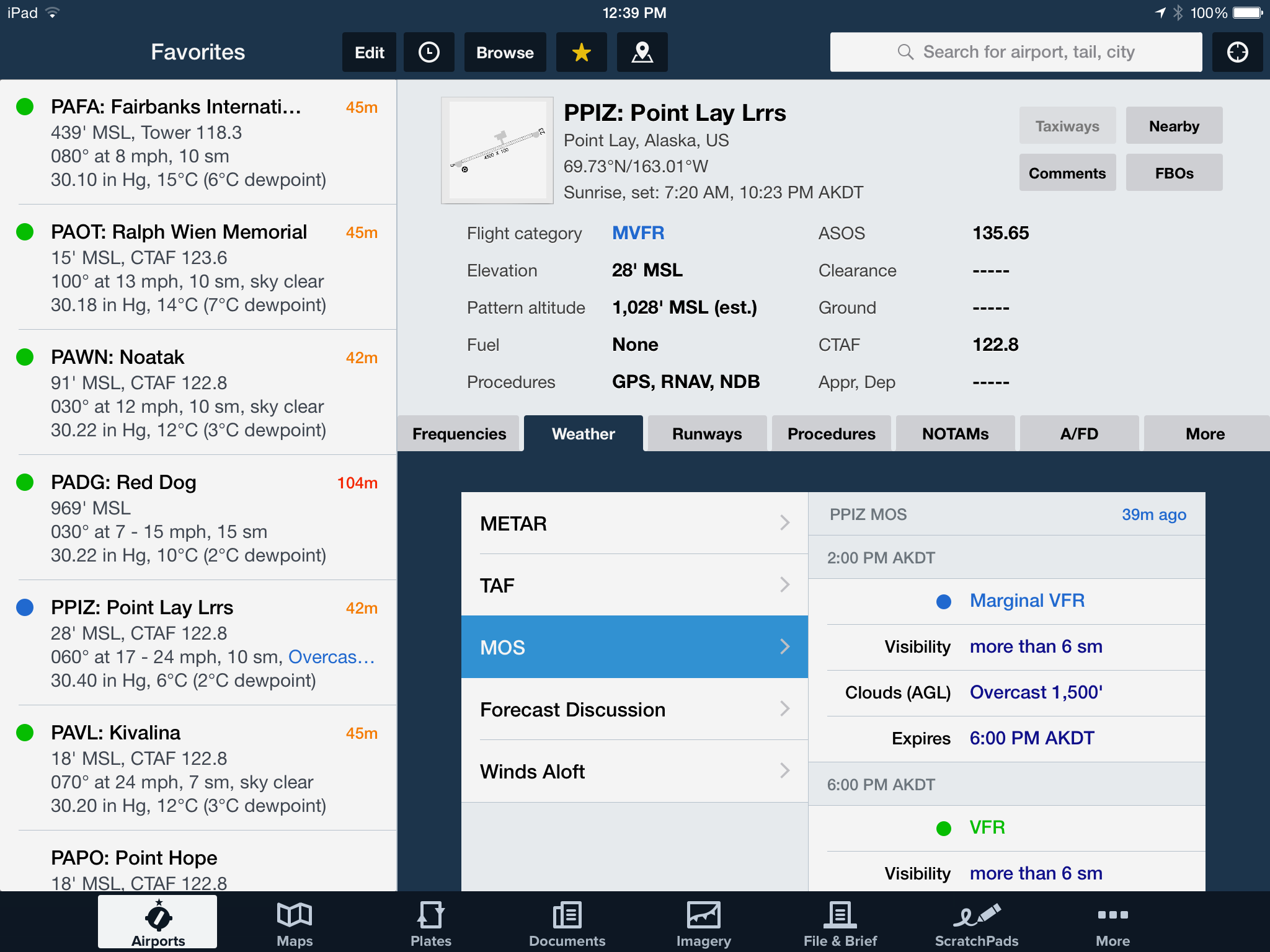

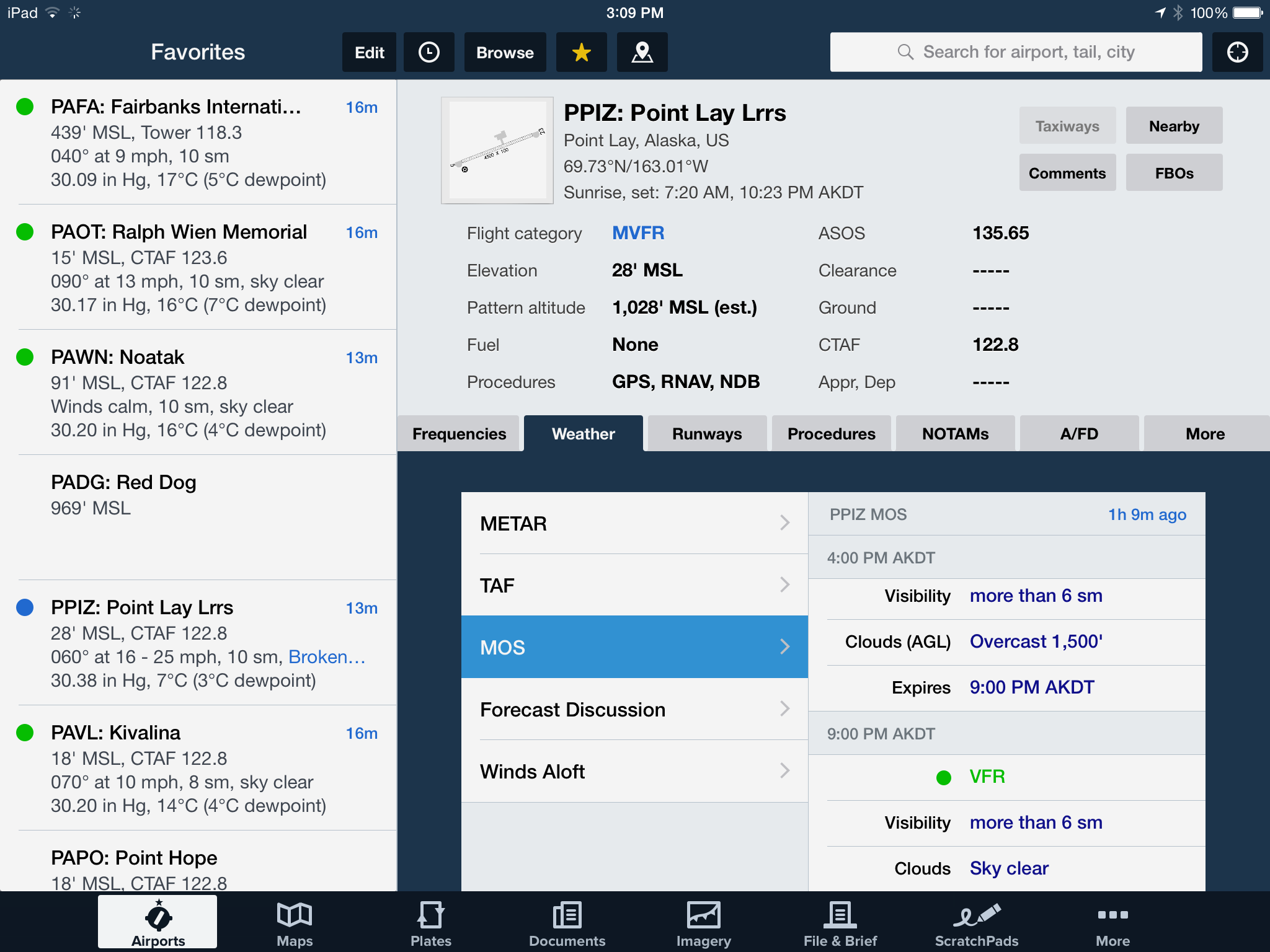

Dropping down to start my first line on Cape Espenberg. Modern avionics are amazing. This moving map on my ipad not only gives me my position, but the position of nearby aircraft and weather from ‘nearby’ weather stations.

The spit that Shishmaref is on.

Shishmaref is heavily armored. The beach really wants to be on this side of the main road.

The sign says Welcome to Shishmaref, but none of the construction workers did.

The progression of beach ridges along Cape Espenberg.

I was pretty lucky with the tides, nearly all my acquisitions were at low tides with mudflats showing. Though I had plotted the tides, practically speaking I was going to go whenever the weather was good given how long I had waited. Fortunately, the good weather was associated with high pressures, and given that the tidal fluctuations here are only 10-20 cm, that high pressure is probably enough to overpower the tidal range.

I’m pretty sure those dark blobs are musk oxen. They seemed too fat for caribou and too social for bears.

Kind of like beach ridges, but different.

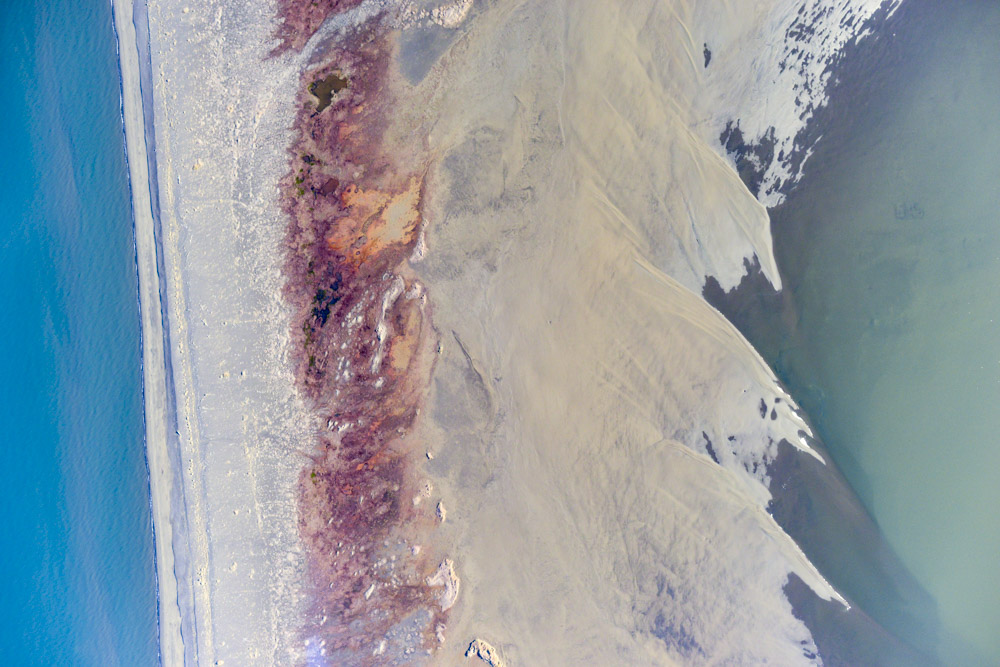

Even though the topography wont be accurate, useful bathymetric information can still be derived from our data.

The freshly paved runway at Shishmaref. Hopefully the prevailing wind is in that direction, as it was directly across today.

This is a disaster waiting to happen.

The connection between north and south, near Wales.

1 September 2016

The weather in the main study area was still down early this morning, but the forecast for tomorrow showed it clear. The forecast for most of the state was continued clear weather for the next several days too. The short way to Unalakleet was also blocked by low fog, so that didn’t seem like an option either. So my thought was today to have an easy day to catch up on sleep, as I was still trying to get over a cold. And having done so much flying, it was also time for an oil and filter change. So once the big jets took off around 9AM, I taxied over to the main ramp to prowl around for a bucket to dump my oil into, which I found from the friendly folks at Ram Aviation who lent me one (and more importantly let me give it back full). By now I could see that our perfectly clear skies of the past few days were no longer so, as the horizon was covered in clouds moving up from the south. My thought for today had been to map the east side of the peninsula and the other side of the bay, but once I lifted off I could see that the entire peninsula was coated in low clouds, obscuring the beaches. The wind was blowing up the peninsula, so I was a bit concerned that the airport would soon get covered. The pilots here are used to flying low over the ocean, but I’m not. Even on clear day I’m still at a thousand feet over the approach end of the runway coming in over the ocean, diving down to land at midfield. So even though the mainland was in the clear, the thought of coming in at 500′ across the inlet beneath the clouds seemed like something I should avoid if possible. So I stuck close and mapped just the northern end and the village of Kotzebue itself. Though traffic here is pretty steady and there is no tower, most planes are equipped with the same ADS-B that I have so it’s reasonably easy to avoid each other, especially given how low they fly and how high I fly, but good communication is still essential and everyone seems pretty friendly. So it was a short day as things go, giving me the chance to get the plane ready for an early departure, take an afternoon nap and catch up on this blog. Hopefully tomorrow will be the big day to finish on the northern coast, then head south for some final village mapping and back to Fairbanks.

By lunch time, the entire peninsula was covered by low clouds, except the northern end by the airport. Leaving the area just seemed like a recipe for disaster. Those numbers are ceiling height in hundreds of feet, so 8 means 800 feet. I need at least 3500 feet to do the work, and even that is pretty sketchy given how far from base I’d be working.

Kotzebue.

They’ve got a 50 mile long peninsula that’s 5-15 meters above sea level, but they put the runway in the middle of an inlet… There’s no way that’s not sinking. Someone should start mapping it to tell for sure…

If you have trouble taking off to the east, you get your choice of falling into the moat or augering into the bluff.

I parked my plane on the cross wind runway, just starting on the lower left where the plane is taxiing.

They have a really nice harbor here. Given the other design choices made in these coastal villages, I’m a bit surprised they didn’t put it on the bluff…

2 September 2016

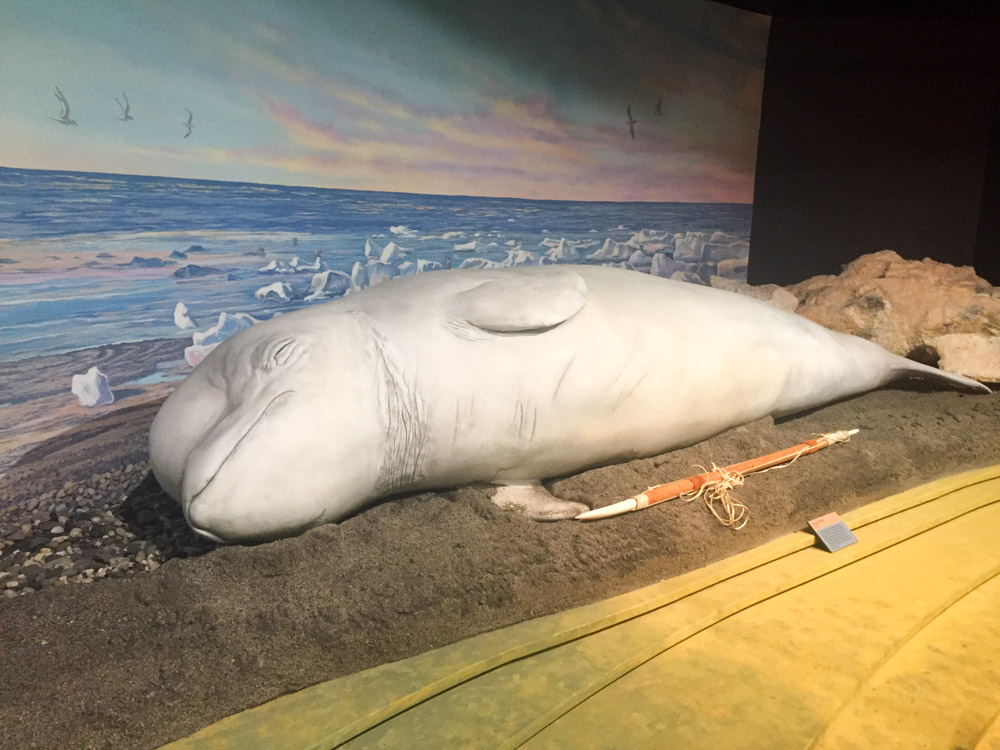

The forecast this morning was for Point Lay to open up in a few hours. Unfortunately this forecast held true until mid-afternoon. That is, every hour since 6 AM, the forecast for it clearing was bumped up another hour. I considered heading south, but the way to Norton Sound was once again blocked by low fog so I would have to take the long way around to get there. And I had by now been here nearly a week waiting for Point Lay to open up, and I knew this good stretch of weather was not going to last forever, so I wanted to give every opportunity a chance. But it was not to be. By 2PM it was calling for it to open up by 6PM, and that was too late for even a short trip given daylight concerns. So I took the opportunity to explore town a little bit. I visited the nice National Park Service museum and gift shop, where I chatted a bit with one of their archeologists about other things to map in the area and found we had many mutual friends. I bought a small book there on climate change in Alaska which I read over dinner, and it was fun reading about all of the scientists working in Alaska on impacts of climate change on the landscape as I knew all of them personally. I can no longer even imagine what Alaska must seem like to someone who’s never been here, or what they must think of the people who live and work here. In any case, Point Lay did eventually open up and the forecast was for it to stay clear all along the coast tomorrow, with winds blowing off shore, so things are looking promising.

Encircled by red. The peninsula was also cloudy in the morning though it cleared later, but by late afternoon the accumulated stress of being on standby all morning was enough work for the day.

In the lower right is the forecast for Point Lay, showing by 4PM the low ceiling should change to clear skies. That was at 11AM. At 6AM it said it would clear by noon.

At noon it was saying it would clear by 6PM.

At 3PM it was saying it would clear by 9PM. It did clear up by about 4PM there, and the remainder of the coast followed soon afterwards. The forecast was for it to stay this way for two days!

Kotzebue is not a dry village…

3 September 2016

The forecast held and today I finished the northern mapping project, which was a great relief.

I was at the plane just after dawn and airborne shortly afterwards. Winds were light and predicted to stay that way, which was encouraging. I flew direct over Noatak and Red Dog again, adding a bit more to each map. As I crested the mountains towards the coast I was again relieved to find that there was no coastal fog and the entire coast all the way to Barrow was in the clear. Now it was time to get to work!

The main issue here, like most of my work in remote locations, is fuel. An additional complication on the coast was a 10-20 mph wind from the north east which made it difficult to predict fuel consumption and range, because my miles per gallon is lower going upwind than it is downwind even though the engine is burning fuel at the same rate, and it never quite averages out the way you might expect, especially today as the wind gradually changed directions both spatially along this 100 mile stretch of coast and temporally throughout the day. So the only way to get a good guess at it was to make a complete circuit up the coast and back, which takes almost two hours, and measure consumption. Compounding this is of course the fear that the fog could roll in any minute during any of my six passes up and down the coast. So my priorities were getting one pass on the barrier island and another one on mainland first so as to capture something everywhere in case the weather did change, and then calculate whether I would have enough fuel to complete all 6 passes. Then I would just do laps until I had just enough to make it back to Kotzebue. The complication there is that given the length of coast, the far end was much further away than the near end, so how much fuel I needed to return depended on where exactly I was. The only runway in the area was at Point Lay, so I also had to consider on which pass by it I should stop to refuel with what I was carrying on board. And of course I was now trying to turn a 3 day project into a 2 day project, so I had to conserve as much as possible. So even though it was 700-800 miles of mission flying, much of it going 70-80 mph, those sort of calculations kept my mind busy the entire flight. In the end I landed at Point Lay twice, using up everything I brought with, and flying as economically as I knew how. I only flew about 1000 miles, but that took 12 hours of actual flying given how the wind was slowing me down and how much I was trying to stretch my fuel.

After my second landing, I had trouble restarting the plane. In general I try only to land at places where I’m comfortable spending a week or two in case the plane gets stuck there, but sometimes, like now, it is simply unavoidable to land wherever the runway is. I could hardly imagine a worse place to get stuck than Point Lay. I know nothing about the community itself, but distance and weather-wise a minor mechanical issue could take weeks to deal with and tens of thousands of dollars, not to mention risk losing the plane entirely when unattended during a big storm. Sitting there in the plane, in the sub-zero wind chill, I considered all of the possibilities, and just hoped it was something simple like I flooded it or it had just cooled down more than I thought. In any case, as the battery was starting to show signs of weakening it eventually kicked over, and once it got going I intended not stop again until back in Kotzebue unless I saw flames or something big fell off. And by this point I had only one line left up the coast, so I hoped if that did happen that it might be over Point Lay on my return.

So my last pass up to Icy Cape was a double dose of stressful. I was by this point right on the edge of fuel and strongly considering bailing on that last line. But I had been keeping track of how much I used on each lap and it appeared I had exactly enough to make it one last time to Icy Cape. So I wrote that number down on the back of my hand and watched my fuel computer tick down every tenth of a gallon towards that number while flying about 70 mph into the wind. With only a few miles left to go I passed my target reserve, but it was simply too close not to finish, and it was a great relief to turn downwind back towards Kotzebue. From Icy Cape it was only 130 miles to Barrrow where I could fill up, but the risk just seemed to high of getting stuck there due to weather or engine, or getting stuck in the dark. By now it was after 5PM and it would take at least 3 hours round trip to get back to here with the fuel and the sun sets around 10 PMish. It was a good thing I didnt because not long afterwards the fog rolled in and I likely would not have made it, and then I would have really been stuck, not having enough fuel to get anywhere except Point Lay. In any case, I was able to finish up the last of project and made it back to Kotz without issue.

While the engine did fine, I did a final runup before shutting down to discovered with some late-night troubleshooting with the good mechanics at Chena Marine Air Service in Fairbanks that I likely had a fouled plug. It was by now 9PM and had been quite the long and draining day, but there was nothing for it except to pull the cowl off and deal with the issue. I had to prowl the ramp once more to borrow some tools, and fortunately the good folks at Ram Aviation once again obliged, which was greatly appreciated late on a Saturday night. It seemed indeed there was a fouled plug and in the setting sun I did a final runup once everything was put back together and was relieved to find that I not only had not made the problem worse but the problem itself was fixed. Shortly before collapsing into bed, I checked weather to find that Point Lay had gone under and the forecast was for a repeat of August weather to hit within 48 hours, so I fell asleep dreaming of being back in Fairbanks the next day.

I didnt beat the jet in, but I beat him out.

Today’s lines in white. That’s a lot of coast.

I got there at a great low tide.

By the time I left 8 hours later the tide had come in, but it wasn’t very deep.

Point Lay. The runway was freshly groomed and nice.

That’s the most serious weather station set up I’ve seen out here. I think a lot of that is their own power supply, but I wonder if they launch balloons here as well?

There is an identical hangar to this on Barter Island. These were the original Dew line hangars. Built tough.

In this satellite image, you can see a large lake encircled by my flight tracks. I’m guessing this lake was their fresh water supply.

Here you can see the pump station is on dry land.

Apparently the lake wall was breached by the river on the right, draining it. Not sure what they do for fresh water now. Hopefully someone is taking this as a sign…

As if they dont have enough problems, the snow fences at left create drifts that insulate the ground and thaw it. So it wont be long before the fences collapse, but more importantly it wont be long before the ice wedges melt out and create a small river that will likely cut through the village to find its way to sea.

Spit formation, complete with ridges.

With the low tide, you can start to get at the processes that shape the land.

Parting shots of the coast where I turned inland.

Not quite under the midnight sun, but it was a long day and I was ready to be horizontal.

The offending spark plug. Not necessarily clean, but cleaner than it was.

I couldn’t get a cab, so I walked back to the hotel along the beach.

This ugliness was forecast to start tomorrow and turn into this. Time to leave.

4 September 2016

With the weather predictions continuing to show severe deterioration and the minor mechanical issues of yesterday, it seemed like time to leave. Having spent a week out here now, and having watched the weather stay bad for almost the entire month of August, I had no desire to spend September here. The low pressure from the south was due to consume Unalakleet and Shaktoolik early this morning, so I made plans to head directly back to Fairbanks. The trip home was uneventful and gave me the chance to see a part of the State I haven’t had much chance to explore yet. The State really is a geomorphologist’s dream.

The trip home also gave me a chance to reflect once again on the past, present and future. It is four years nearly to the day that I took my first flight lesson, and three years nearly to the day that I completed my first mapping mission, coincidentally based out of Kotzebue. Over the next two years, I worked on any project I could that could help me determine and improve the accuracy and precision level of my system and published a slew of papers demonstrating that my results are superior to those involving hardware that costs millions. And in the past year I have been able to successfully apply those methods to enormous projects and build a thriving business based on it, digging myself out of the enormous debt of the five years previously it took to get to that point. I never really woke up having had the American dream, but I think I just made it come true. In terms of the work, we have a ridiculously warped sense of spatial scale in Alaska so I always have to keep comparing areas here, which look small compared to the size of the state, to equivalent areas in lower 48. I have by now personally mapped more area than the 3 smallest states combined, at a resolution fine enough to measure the size of a Winnebago dog still large enough to get carried away by an eagle. The length of coastline that I have mapped is longer than that from the tip of Maine to the tip of Florida. I always chuckle when I think of mapping the east coast. Imagine being able to get fuel or find a mechanic every 50 miles rather than every 300 miles! Imagine having your pick of thousands of hotels and resorts along the way rather than four! Imagine having 1000 weather stations en route rather than 12! But then I also imagine the competition for such a job. With dozens if not hundreds of airborne remote sensing companies down there, most of which jealously defend lidar as the only legitimate means to map coastlines, it would have been impossible for a nobody like me to get a contract for such work, despite that such a lidar project is $10M minimum at coarser resolution, whereas what I’ve done with a fraction of the infrastructure cost 30 times less. We have a lot of salmon streams here, but at some point every single one of those streams was colonized by some salmon that either got lost or got fed up with being part of the crowd. Without those salmon trying something new, most of which died in the attempt, we’d only have one salmon stream. I think the country needs a place like Alaska if only for that reason, a frontier where a frontier mentality can still thrive, where new ideas can be tested, most of which will fail, but some of which can change the world. Alaska is still a place where wing nuts can largely go their own way, whether in private life or in politics or in business, but of course the trend is always towards civilization and forming a status quo, making it uncomfortable enough for those with that frontier mentality to feel compelled to seek out yet another stream. I guess it cant be any other way, as frontiers become victims of their own success — by demonstrating that something new works in a competitive environment you guarantee the crowds will follow, and with crowds come rules, and with rules the frontier is lost and those that conquered it displaced. And I guess that is the real story of how the west was won, time and time again.

From Wales to Icy Cape, that’s 4400 miles of flying in 6 days, taking some 32,000 photos. In total that’s about 25,000 miles of flying taking about 200,000 photos, covering about 2000 miles of coast to 1000-2000 meters inland at 10-20 cm resolution. And that’s how the west was won, this time.