50-60 Hindsight

I spent my 50th birthday documenting and measuring landscape change in the Arctic as part of projects that began 60 years ago or more, giving me occasion to reflect on where I’ve been and where I’m going.

This has been a pretty wet year in northern Alaska. Unlike last year, forest fire smoke has not been the big flying challenge but rather avoiding the rain drops and thunderstorms. I have been trying to get out to western Alaska to finish up several coastal projects all summer, but the combination of weather, work, and life has not been favorable towards that goal. The past two weeks I’ve been on heightened standby to eek out whatever weather windows I could, but it wasnt until 2 days ago that the constraints looked like they were disolving. The general plan was to head to Kotzebue and base from there for a week to knock them all out — mapping Bethel, Shaktoolik, Cape Espenberg, and the stretch between Point Hope and Point Lay. In addition a bit inland from there I had a project to map oblique photos taken at low level in the lower Noatak Valley in the early 1950s, taken when my plane was brand new and when topographic photogrammetry was a science that was really only 5-10 years old.

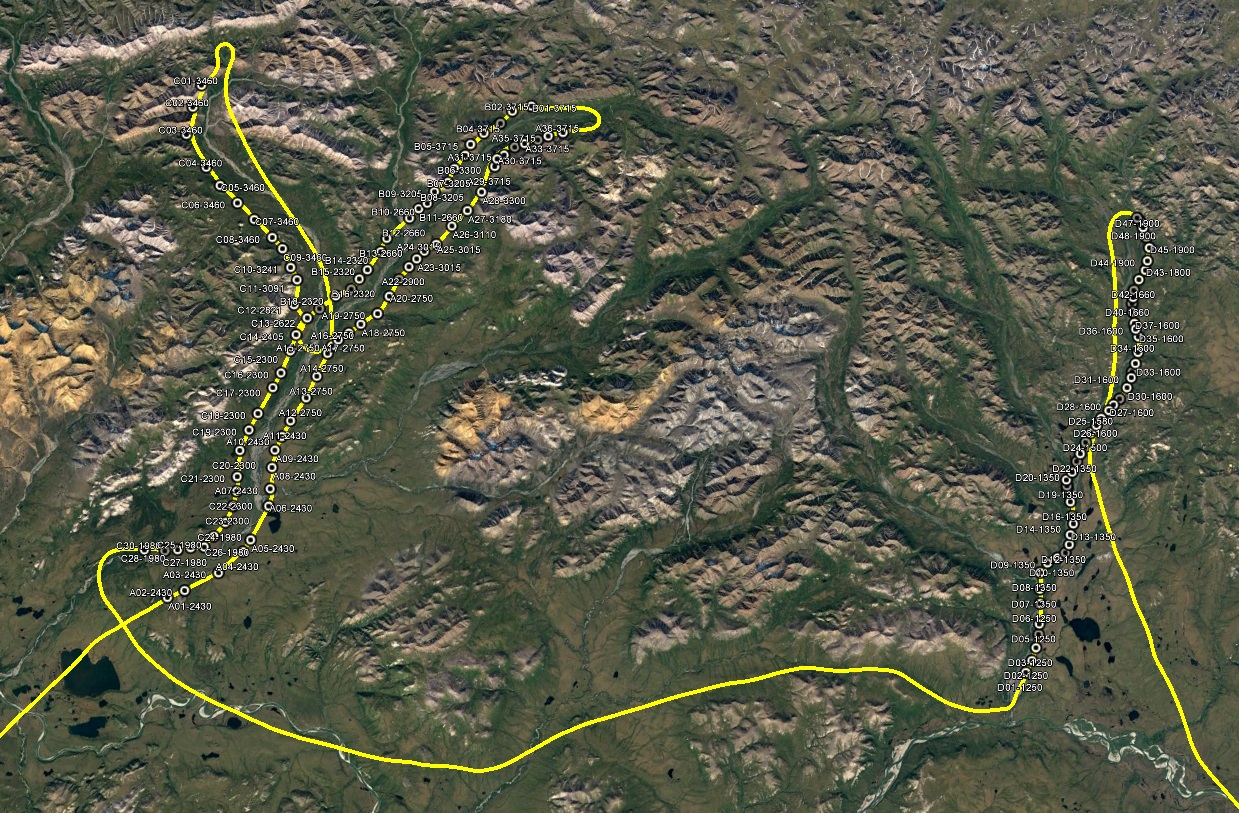

The oblique project is an especially interesting one to me. These photos were taken with 9″ film out the side of a fairly large plane, similar to the cameras used for this project that were oriented vertically. Ken Tape repeated these photos early in his career over 10 years ago and in combination with substantial field work was able to document roughly a 30% increase in biomass due to shrub expansion caused by climate change here, and his initial paper remains the most widely cited paper on the subject. That work was done before the explosion in digital camera technology and digital photogrammetric mapping. So the idea here was to take a first pass at utilizing those new technologies. Dave Swanson is the lead physical scientist in the Noatak National Preserve where much of this work was done, so he took some painstaking efforts matching the original photos up with Google Earth views to reconstruct those flight lines and match up the perspectives and lens. My role was to take the photos from those locations.

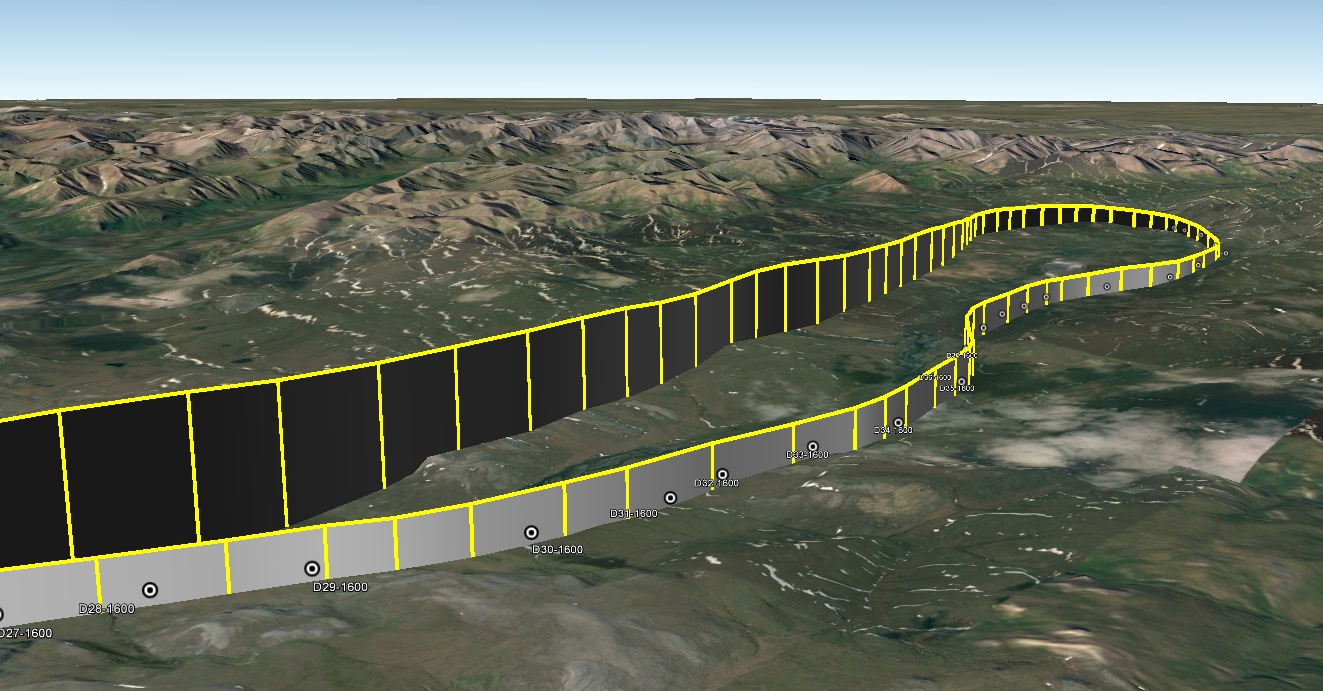

I havent shot obliques since I began shooting verticals, so it was a learning experience for me to adapt my system to the new challenge. I experimented over the summer with different configurations for arranging the camera setup. Ultimately I decided to place it behind me by extending my existing camera mount upwards and shooting out of the side window. The project came with specs on lens focal length and pointing angle. The original guys likely had the door off with the camera either suspended or on a pedestal, while they sat on the floor and shot manually. My system needed to replicate that as closely as possible — shooting out of the left side of the plane, with the top of the frame along the horizon and the forward edge of the frame perpendicular to the flight path. Ken did something similar, but without Google Earth he had to match up photo locations from the topo maps and then shoot single frames from a helicopter with old photos in hand. As I’m in a small plane on my own, I couldn’t hold up the original photos to match them up, so I would be shooting nearly continuously with substantial overlap. This overlap was not simply to pull the best replicate from the shotgun blast of imagery, but also to use them photogrammetrically to make DEMs and orthophotos that could be used quantitatively.

I hung a caribiner off the wing tip to align the camera, such that I just needed to have it in the corner of the frame to meet the pointing angles.

I mounted the camera on top of my existing vertical mount, such that I can switch between them easily without having to move either.

I tested a bunch of 50 mm lens and this one is the sharpest of any lens I’ve used, and not that expensive either.

I draped some black fabric behind the camera to prevent glare on the window from getting in the shots.

So ready for anything, I woke at 4AM on the 4th to head west. The skies were generally clear, but there was a low ground fog nearly everywhere, as temps were cool and we had just finished with a lot of rain. Unfortunately it seemed a large low pressure was moving in from the south west that threatened to shut down the west coast yet again. I headed generally west, fortunately finding rivers of open ground between the fog until I got to about Tanana, where it seemed to be continuous in every direction. I almost turned around, but I decided to skirt the open hills a little further along the Yukon, where I found about 30 miles later that the fog was gone to the north, so I headed that way. My original plan was to head to Bethel first, swing up through Unalakleet and then base from Kotzebue for the remainder, but at this point I headed straight to Kotz for fuel and to make a new plan based on the latest weather, as its about 5 hours for me to get there and by the time I got there it was almost noon. It did indeed seem like today would be my only day for mapping in the area before getting shut down for the rest of the week, or spend a week of fighting marginal conditions in a remote area new to me, and so late in the day there was nothing I could finish there in a single day. The weather to the north and east was looking great though, so I made the command decision to map the obliques in lower Noatak only about 45 minutes away then head back to the eastern Arctic to make the final map for the year of the glaciers in the Peter’s Lake watershed and McCall Glacier, and then try to get home in time for my birthday. So after some camera rearrangement and refueling in Kotz, I headed north to repeat history — not just the obliques but essentially my flight route of about a month ago.

Weeping Angel wasn’t very happy about the ground fog, but we picked a route through it without too much hassle, though not exactly in the right direction.

This is about where I almost turned around.

But not much further along it opened up completely.

I had seen this sand dune in Google Earth a bunch and always wanted to map it. Today I got my chance.

I reconfigured for obliques on the ramp in Kotzebue. Note the caribiner hanging off the wingtip at upper right. Fortunately I remembered to remove it before I took off..

I reconfigured for obliques on the ramp in Kotzebue. Note the caribiner hanging off the wingtip at upper right. Fortunately I remembered to remove it before I took off..

The weather was almost perfect for the task. Another large constraint of the job was to do it with no cloud cover that would create shadows on the terrain, trying to match the conditions of 60 years ago, as well as to do it with leaf on the shrubs. Given the lack of weather reporting in this region, that was a tall order, so I was glad to capitalize on the opportunity. There had been about a 10-15 knot wind from the east out here, but it was smooth, until I got below terrain level to take the photos, mostly less than 1000′ feet above ground level in valleys within mountains that were 2000-4000′ high. Here the bumps increased substantially and the early afternoon thermals were starting to kick in. Relative humidity was low, so fortunately the thermals were not leading to buildups, so it seemed I was in the right place at about the best time I ever would be, so I went for it.

The challenge here is that I’m flying a plane with a small engine heavily loaded with fuel at low level into narrow twisty valleys into ascending terrain that I’m unfamiliar with, while following waypoints on my GPS that picked from a map and trying to keep the aircraft level in 100-200′ up and downdrafts with a plane that can maybe muster 100-200′ on a good day while monitoring camera exposure and photo quality. It was all a little intimidating as there was a lot of potential for catastrophic failure by paying attention to the wrong thing at the wrong time. So I wasn’t long into flying the lines when I decided I was never doing this again, but generally speaking things went well. As the waypoints were picked from Google Earth, the elevations were the biggest challenge as they sometime rose faster than I could and as a result sometimes had me trying to fly through terrain when I could not climb quickly enough. But I hit most of the points spatially within 20 meters probably except when diverting, and even then it was only a few hundred meters off. One line had me only 200-300′ off the ground at times and these I flew a little higher, as between the turbulence and ascending terrain taking me around corners I couldn’t see past, I thought there was no merit in finishing the job on foot. My only moment of near-panic came when I realized that we would be getting a lot more data if the camera was arranged vertically, as in landscape mode we weren’t picking up the whole river flood plain as it was getting cropped, and then I realized that if I’m realizing this now maybe Dave had already realized it and that I was supposed to be doing it this way in the first place. There was no way for me to reach back, change the camera orientation, re-level the camera to the correct specs, and try again, and at this point it was too late in the day to back to Kotz to do it, and I was pretty sure I set things up the way the contract read, but it was a month or more since I read it so I was starting to have second thoughts. In any case, all of the other planets were aligned so no sense stopping now, though all the while I was dreading having to do this again.

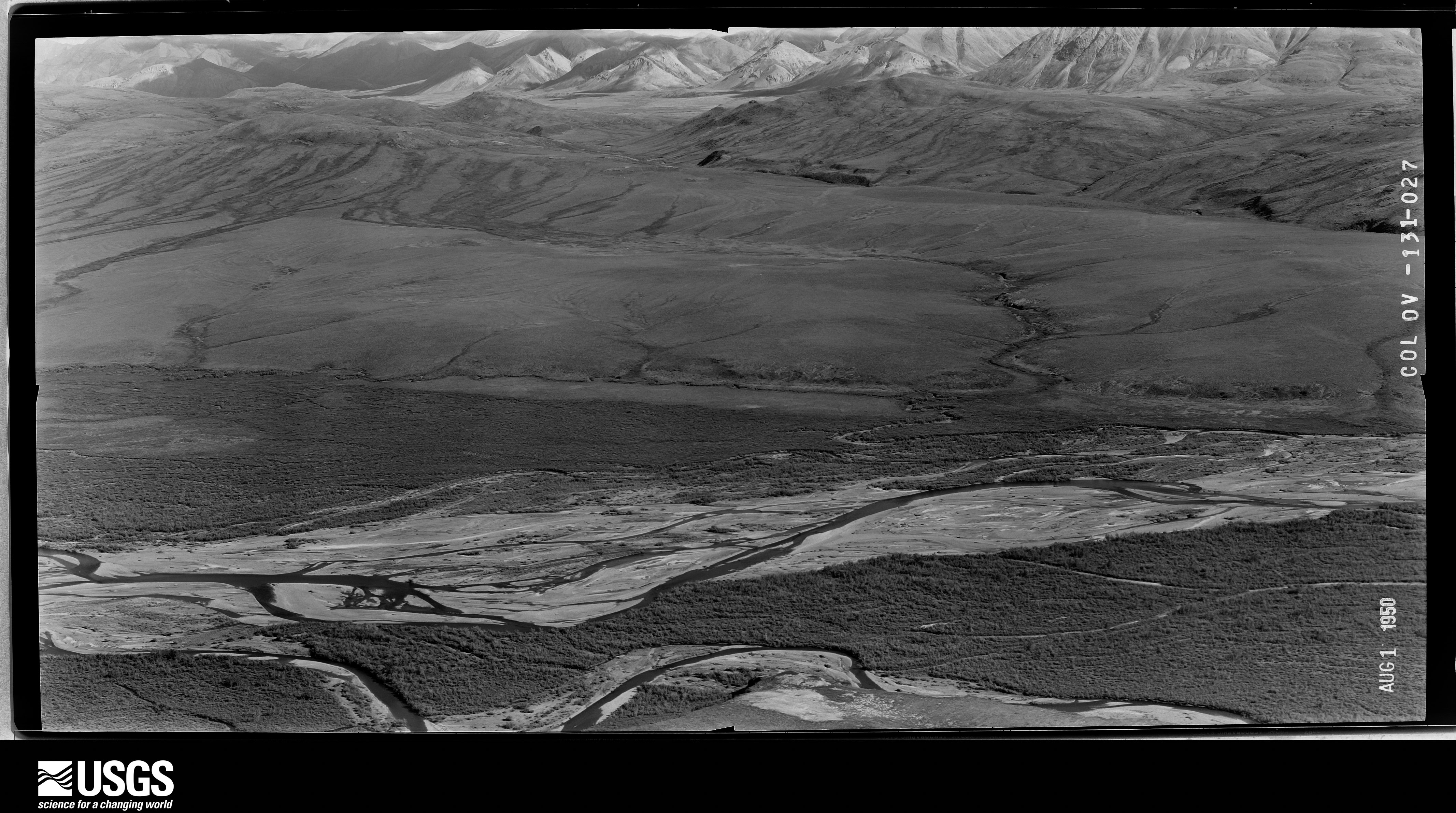

Here are a few of the original photographs. I have forgotten the whole story since Ken told it to me way back when, but I believe they had rigged the camera to take double-wide exposures at 9″x18″. These were taken Aug 1st, mine on August 4th 66 years later.

These are the oblique lines. It was quite the challenge to nail them.

This line had me almost at ground level. I cheated a little higher, and climbed up on the way out of the valley.

Here are a few of the several thousand photos I took. I haven’t yet spent the time to match up repeat pairs with the originals, but I think you’ll get the idea.

Once I had finished the lines I turned south and had another decision to make. Like last time I was here, I had the choice to head to Kotz or Bettles for fuel. I was afraid of getting stuck in Kotzebue for a week doing nothing, and Bettles would get me in range for Peter Lake the next morning which was forecast to be clear, calm, and low relative humidity. Plus the field team was now there and could give me local weather reports. The challenge was that if I headed to Bettles and could not get in, I likely would not have enough fuel to get back to Kotzebue, as I had flying nearly full throttle in the valleys to fight the thermals, but I could land back at Dahl Creek at that point and just wait for someone to bring me more. So I headed to Dahl Creek to refuel from my jugs and make the call there. Though there are two villages with much bigger runways only 10-15 miles away, I like Dahl Creek because its much more secluded and if I have a problem I can just sleep under the wing without worrying about what the locals might think of that, as there dont seem to be any locals there. It’s also in cell range of those villages, so I checked in with weather and headed to Bettles for the night. The first thing I did once there was open my laptop and check the specs on the camera orientation, and was relieved to find that I had it right. I also processed part of a line photogrammetrically and was relieved to see that there were no issues doing this from an oblique view rather than my normal vertical one. I think these photos will be a great check-in on the state of shrub expansion, but I think they are probably just the first step towards putting modern tools to full use, as making such maps using my normal methods of overlapping vertical flight lines will not only yield a more comprehensive and quantitative result, but will be a lot safer, easier and cheaper to repeat in the future, whether by me or someone else, as that really is a job for a helicopter.

On the way back to Bettles I fooled with taking some oblique scenery shots.

There was some scuz, but it didn’t get in the way and made for good backdrops.

Lot’s of fires in the area, still a bit active. In the foreground is an oxbow lake that I think formed only this year, or maybe just gets reactivated as a river during high water.

I like Dahl Creek. Not sure what all goes one here, but I’ve never seen anyone around.

I like being able to park the plane and walk to the bar, like in McGrath and here in Bettles too. Food is good, staff are friendly, and the beer is cold.

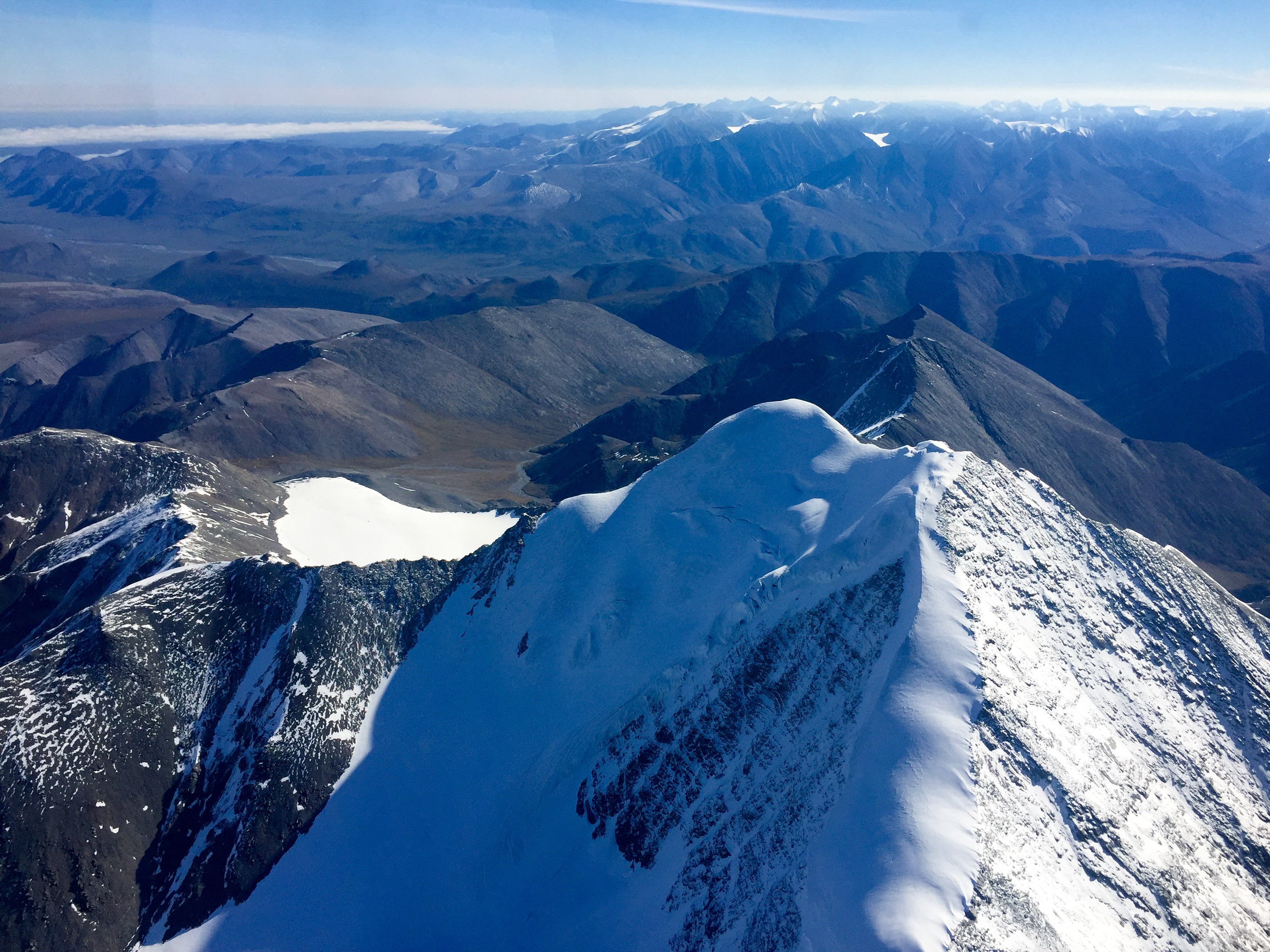

The next morning I checked weather to learn I had made the right call heading this way. The west was getting pounded and the east calm and clear. The Arctic Village weather cameras were down again, but Darrell texted in a 5AM that conditions seemed perfect. So I was airborne before 7AM and hoping for a successful birthday flight. There was some skuz and strong winds right around Bettles, but soon I was above it all and getting a tremendous view of the the central and eastern Brooks Range without fighting anything. Flying almost becomes pleasant in such circumstances.

I was looking forward also to seeing McCall Glacier again and this flight had by now become special in many ways, not the least of which was that it was on my 50th birthday. I couldn’t map it when I was in the area in July due to weather and fuel. And I was feeling a bit sad and guilty that the overall project has fallen into such disrepair and needed a pick-me-up to know that at least I was continuing the volume change measurement time-series. My major goal from the beginning of my efforts there in 2003 was to create a sustainable research project. One of the key parts of my plan for doing that was to install weather stations that could record for several years, in case of gaps in funding or anything else prevented us from getting out there. These worked great in general, up until the point where the gaps in our visits started. I had installed some poor solar charge controllers and these had shortened the battery life. For the past two years I’ve been trying to get fresh batteries in there, but in the end I guess those efforts have been half-hearted due to the other key component of my sustainability plan, which was to control our own logistics by using our own aircraft. Since 2008 this has been a major part of my life, but the complications associated with doing that essentially unraveled all my plans for the project and my life. After a decade of trying to move and build mountains towards these ends, the unmitigatable impacts of various once-trusted humans randomly pulling out foundational roots of those mountains led to them being reduced to rubble repeatedly, causing me to essentially to start from scratch yet again in 2012. Standing on this rubble I decided that the only way to rebuild it was to do it completely on my own, and this has taken some time. The first part of that plan was learning to fly and buying a plane, then developing fodar and turning it into something that could I use to fund my science by helping others, then making that money, then paying off the massive debts of my past attempts, then getting ahead, and then renewing the McCall program out of my own pocket and under my own control. So 2013 is when I learned to fly and bought my plane and within a year had both figured out fodar and landed on the glacier on my own. My plane, however, was never one really meant for that purpose, and is marginal at best even when empty, but in the end was all I had to work with. Last year I got to the paying off debt stage and now, if everyone actually pays their bills, I will be at the ahead of the game stage, and then hopefully I can refocus on the glacier. So it has all of course taken longer than I hoped and been a lot more work finding the circuitous pathways to get me there, but with this flight I felt like I had finally arrived where I had hoped I would have been almost 7 years ago now.

Fortunately the weather held. I flew slow and leaned the mixture hard direct to the glaciers, conserving fuel to maximize my glacier-mapping time. After finishing the Perers Lake glaciers, I flew a line over Esetuk Glacier. A single line isn’t nearly as good as a block, but its a whole lot better than no information, and with some careful flying I can get the whole thing in one line. Then I mapped a block over McCall Glacier and its nearest neighbors. It had snowed in the past few days, so all of the glacier ice was hidden beneath a thin opaque layer white, but for volume change measurements this is inconsequential. My nostalgia for the place hit hard as I flew over the Krisscott Glacier and then up McCall, where I could see my weather stations sitting idle and recall the hundreds of trips I’ve taken up and down that valley. Even in the past two years I can visually see the changes, dwarfed by those since 2003. Though it would still be clearly recognized by the scientific pioneers here from the 1957, over the 60 years of research here we have a record of the largest landscape changes in the US Arctic second to none. Now 50 and my scientific career cresting its peak, my goal is to leave this project in a sustainable shape for the next 60 years, by which time the glacier will have largely disappeared, if not disappeared completely, if current trends continue. So I tried to soak in as much of it as I could now, both personally and scientifically.

Mt Chamberlin. It may not be the biggest in the Arctic, but its still pretty.

Peters Lake. The field team is out there somewhere.

Gooseneck, McCall and Krisscott Glaciers, left to right.

After wrapping up McCall, I hit another target that had been on my list for a while. Though only 20 miles away, I had never mapped Okpilak Glacier before despite having been mapping nearby a dozen or more times. It’s all just on the edge of my fuel capacity, where even minutes matter, and I never made the time for a dedicate mapping block here. But I figured just like with Esetuk Glacier, I could run one line up its length on my way out, and having done so I think I should make this a regular part of the mission based on what I saw.

Next to McCall, Okpilak Glacier is probably my favorite. In large part this is due to my several trips there in 2004-2007 when I was able to repeat a set of photos taken about 1907 by Ernest Leffingwell, my favorite Arctic scientist. He schlepped a large format camera in there by dog team and foot, as part of a 5 year solo scientific effort in the area that culminated in a manuscript he published later documenting landscape change that is still referenced today. It’s hard to describe what I felt when I first found the cairn he left behind at his primary photo site in 2004 and later discovered several other photos he had taken there but not published and realized he had taken panorama, but it was an addictively good feeling. I repeated this panorama in gigapixel format in 2007, before gigapixel photos were even a thing, and Ken Tape used this photo pair in a travelling exhibition that has now been to 10 or more museums around the country. When Ken and I went back for that photo in 2007, we found that the leading edge of the wierd outcrop it was on had crumbled off, taking the cairn with it; you can find a photo of the new camera set up near the top of this page. Yesterday when I flew over I discovered that whole outcrop (!) had slid down hill. This was area almost large enough to land a cub on (another secret desire I had for the future). I dont really understand how it formed, but it almost looked like a glacial end moraine, but not really. It might have been part of an earlier slide which somehow anchored itself and formed the bench, but it had a pretty meadow on it. In any case, it’s gone now, and the only way to repeat that perspective in the future will be with a technique like fodar that allows us to synthetically recreate it. The glacier itself has drastically retreated, probably the biggest retreat of all glaciers up here. In large part this is due to the large terminus being cut off from the upper ice by a steep bedrock outcrop, which was an icefall in 1907 and partially exposed in 2007 that we skied around but is now just rock. In 2008 I paid a commercial company to map all of the glaciers in this area, and though those data have some issues and those issues led to a four-year ordeal in which we got them to make similar maps for the next 3 years until they got it right, these maps combined with our twice-annual surface elevation mapping of McCall since 2003 and all of the maps I’ve made since 2013 form the most comprehensive full-glacier mapping time-series of any valley glaciers in Alaska and probably any outside the Alps, and seeing this change yesterday served only to reinvigorate my desires to put those data to good use to document what will certainly be the accelerated loss of glacier ice over the past 150 years.

Esetuk Glacier terminus. Last I was there the ice extended over the mound near center. We have some ground panoramas here from the 1980s which have yet to be repeated.

Krisscott Glacier terminus. The large outcrop in the center of the terminus was covered by glacier ice when Kris Scott and I skied over it 2003 while mapping the surface elevations. In many respects this would have been a better glacier for long term observation, as it is straight with no tributaries and facing directly north. But an important constraint in the 1950s was having a glacier large enough to drop parachutes loads of supplies onto, as well as close proximity to the best mountain climbing in the area.

At top is Leffingwell’s 1907 photos that I made into a panorama and at middle the photo that I took with Ken in 2007. I made this print for an art show for Tom and Susan’s Calypso Farm and Ecology Center in 2011. The theme was sheep and wool, thus the sheep at left for the 200 year repeat. I based the vegetation distribution for 2107 image on Ken’s work on shrub expansion using the photos I just made the oblique repeats of.

Okpilak Glacier terminus. To the left of center you can see the dirt outcrop that the original 1907 photo was taken from has slid down into the valley floor. It may have been created when Okpilak Glacier was much larger and hung up debris falling from the glacier at right, kind of like a kame but not really. With Okpilak Glacier no longer buttressing it, it was apparently unable to resist gravity after 150+ years. When we mapped Okpilak in 2004 we were able to ski down either side of the bedrock outcrop almost all the way to the dirt one that fell. One hundred years ago, the glacier extended all the way in the bottom left corner of the photo.

McCall Glacier terminus. It’s tongue is not retreating as fast as Esetuk or Okpilak, but the bedrock topography is different here. What matters most is volume change, and these are roughly equal, and why its dangerous to put too much weight into terminus position fluctuations in terms of climate change.

The confluence on McCall Glacier. Our camp is on the outcrop at bottom.

The trip home was largely uneventful, except for getting sung Happy Birthday by Susan from Kavik over the radio which was definitely a first. With an accurate fuel computer and the rare fortune of accurate dial gages on the tanks, I was able to coast all the way to Ft Yukon to refuel and still have minimum reserves, which doesn’t take much when you’re burning less than 6 gallons per hour. Upon landing in Fairbanks I sat under the wing for a while and reflected over the history of this project and what I felt was the latest milestone in it. Now, on step with Plan #16, I hope I’m finally entering that era of the project I’ve struggled to reach for so long. Over these years I’ve learned that I’m a lousy academic scientist and a lousy businessman, I just don’t have the personality that’s expected for those roles. My natural approach towards science is much more along the lines of the way this guy approaches plumbing, and my current plan largely follows his philosophy. There’s a hundred and one ways to go about being a scientist, but at some point there was only one, and it was only through the successful efforts of another hundred renegades that the rest became established. So I guess only time will tell whether there’s really one hundred and two ways to go about it, but in the meantime all I can do is keeping putting one foot in front of the other while keeping the goal in sight.

The White Mountains just north of Fairbanks seem to be scuz magnets. Here is Victoria Mountain near Beaver Creek.

My version of sky writing I guess.

After I landed I checked weather to gage my calls. I’d still be sitting in the rain in wind had I not headed east.

My least favorite part about getting back home.

For my birthday, Kristin and Turner took me to the fair so that I could get my turkey leg.

Coincidentally to the Okpilak Glacier sheep show print, we found this photo of Tom and Susan and the girls in an old display in the vegetable section of the fair shortly after bumping into them all there. I remember when that photo was taken like it was yesterday, yet somehow the girls are now 15 and 17.

I’ve made a lot of mistakes in the past 50 years, but I got one thing right…