Mapping Denali — Sourdough Style!

We mapped the tallest mountain in North America last weekend! This blog tells the tale of how a family of three made the best map ever of Denali, almost on a whim. The scientific side of this story can be found here. Click here to learn how you can help make more maps of Denali.

I took this photo in 2016, while mapping about 1/4 of Denali National Park and Preserve to establish a baseline of change for terrain below about 9000′. I mapped in again in 2017, and these data are being used by the Park Service’s earth scientists to understand this dynamic landscape on the spatial and temporal scales needed to observe these dynamics while in progress, rather than after catastrophes occur. So I spent a lot of time in the plane with a view like this, day dreaming about mapping the Big One itself.

This story has roots that go back nearly a decade. I’ve never had any desire to climb Denali, but I imagine my desire to map it is similar to what those climbers feel — it’s just there, daring me to test my skills against its challenges. While I’ve been an earth scientist for 25 years, my real passion has been engineering and using contraptions to allow me to make earth science measurements that no one else has made. For the past five years, that passion has manifest in fodar, a photogrammetric process for measuring the shape and color of the earth’s surface from the air. It’s basically what is driving the drone craze right now — drone-based fodar is a cheap and accurate way to measure topography and, by repeat-mapping, changes to topography. But drones have limited utility in Alaska and to me the real challenge is mapping large areas at drone resolution but at an accuracy superior to any other technique — we know our enormous State is changing, but we can only guess at how widespread those changes are without such measurements. For example, permafrost thaw and settlement, coastal erosion, glacier melt, and vegetative change are all processes that occur on the millimeter to centimeter level over millions of acres, and unless we can track these changes at this process level, our ability to understand and model these dynamics is limited to what we can deduce once the changes become massive enough to see with coarser tools. That is, Alaska is just too big and too inaccessible to casually make the observations we need to create the models we need to accurately predict how our State will change in the future, and without such models we cannot begin planning for those changes now while they may still be affordable to deal with. So five years ago, at the age of 46, I bought a plane, learned to fly, and developed this fodar technique to put a dent into that problem, and over the past 5 years I have gradually turned into a fodar cyborg: fusing myself with airplanes, cameras, GPS, and computers to map Alaska they way it needs to be done.

As part of those efforts, I spent the past two summers in Denali’s shadow mapping enormous areas of Denali National Park (eg, Project #10 in this link). It really is an amazing mountain, standing so tall above other really tall mountains, with its double peak and gobs of glaciers falling off of it. But what’s happening to those glaciers? Are they wasting away as fast as the “low” altitude glaciers down at 10,000′? Are they growing? How can we tell? A few recent field studies have shown that high-altitude snow accumulation is increasing over time. But it’s suicidal to make direct measurements over most of Denali and other tall mountains here, and even if we could there isn’t any funding for that — there are only half a dozen glaciers in all of Alaska that have long-term field measurements, and every one of those is under constant threat of failure due to funding. Satellites can do a few useful things, but the changes have to be large before they are noticeable. A different airborne technique than I use made the only other map of Denali since the 1950s in 2013 and found it’s peak to be 83 feet shorter than the published value, but a subsequent field study found that value to be wrong by 73 feet (!). That doesn’t mean those data aren’t valuable for glacier studies, just that there is a lot of noise associated with those data that limits its use. But perhaps more importantly, that mapping effort was an expensive, one-time deal, and what we really need are measurements over time to find and track change. Thus I had two compelling scientific reasons for mapping Denali: definitively answer the question of how tall Denali is and track changes in high mountain glaciers and snowfields there. But mainly, I just wanted to do it.

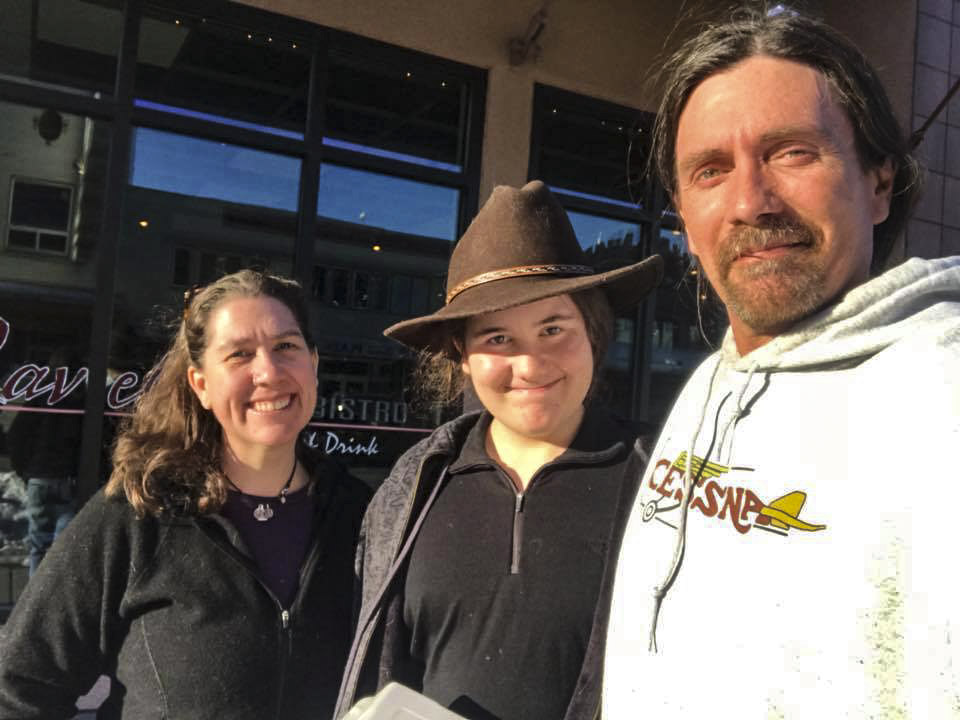

This is a good example of when it would have been better to clean the house rather than to try to map Denali with your family in the plane…

To map such a tall mountain would require a plane that I could afford that could overcome the challenges of weather and high altitude flying that the mountain posed. Having spent so much time in its shadow, I knew how violent the weather could be near there and how rarely it was surrounded by both clear and calm air. Sometimes it’s obvious when the weather is bad on top because you can see the clouds ripping over it. But sometimes those clouds aren’t there to give you a visual indication, and the clear air turbulence surrounding a mountain tall enough to poke into the Jet Stream can be strong enough to rip the wings off a light airplane. Even if the turbulence wasn’t that strong, downdrafts burbling over the mountain can be strong enough to slam a small, underpowered plane into the ground. Besides these gloomy outcomes, there are the more mundane challenges of being in thin air. Engines, like people, need oxygen to function, and oxygen is in short supply at 20,000′. So to get up and over the mountain safely, typically one would use one of the many excellent aircraft designed for high altitude operations, typically having one or two turbine or jet engines. Unfortunately I could not afford any of these types of planes. It can be done, ableit marginally, with a single piston engine like those found in most small aircraft, but the engine needs supplemental oxygen supplied by a turbocharger. There are not many of these around any more, I think because those who want to to fly high and fast can afford their own jets and those that fly low and slow don’t care about flying high. So I dont think the nice people working at Cessna in 1966 had in mind that the 206 coming off their assembly line should be used for mapping the tallest mountain in North America, but that’s exactly what I had in mind when I saw a turbocharged version come up for sale in Fairbanks in winter 2016.

Lenticular clouds like these make for pretty pictures, but they indicate the type of winds that could rip the wings off your airplane..

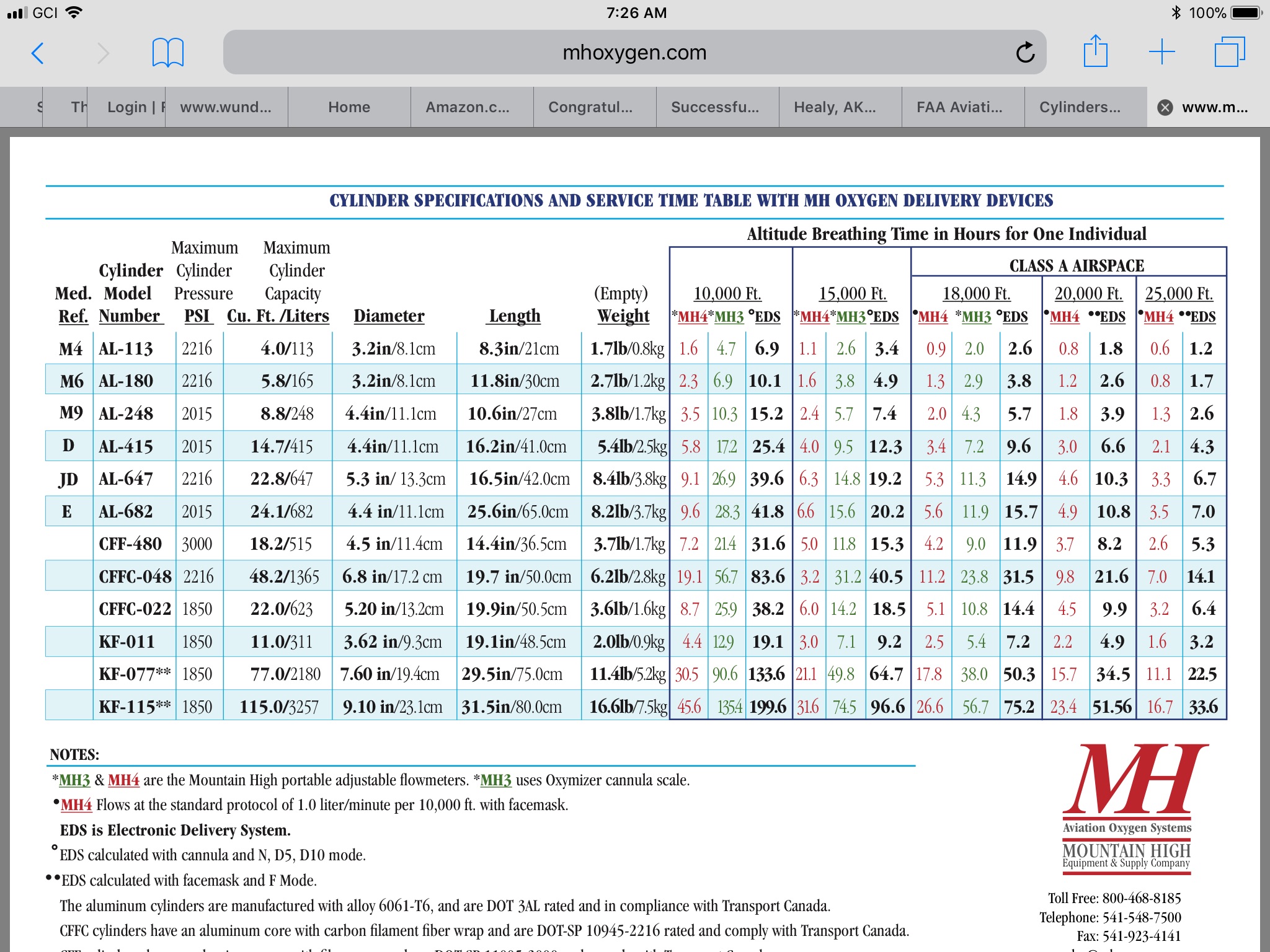

Buying a suitable aircraft was an important step along fulfilling this dream of mine, but important challenges yet remained. Just because the plane could theoretically reach 30,000′ doesn’t mean the occupants could. The turbocharger is like an oxygen mask for an airplane, but it doesn’t help the occupants — without supplemental oxygen, occupants of an unpressurized airplane operating at 25,000′ could pass out in minutes. So I had to sort out a supplemental oxygen system, which the nice folks at Mountain High helped me with. The system I purchased would theoretically give me about 4 hours of oxygen, flying alone as I normally do. Unfortunately, my license does not allow me to fly above 18,000′, as I skipped over that test in my haste to go from having never flown to getting a commercial licence so that I could complete some mapping projects with a mapping system I had yet to build. So having sorted out the oxygen system over the summer, my plan was to sort out getting an Instrument Rating over the winter so that I could legally fly over 18,000′ on my own. Fate had its own ideas, however, and my new plane spent the entire winter without an engine and I only got it back a few weeks ago. I wasn’t in a rush, however, as I knew the mountain would still be there when I was ready.

My plane spent the entire winter looking like this. You just never know what you are getting into when you buy a new plane.

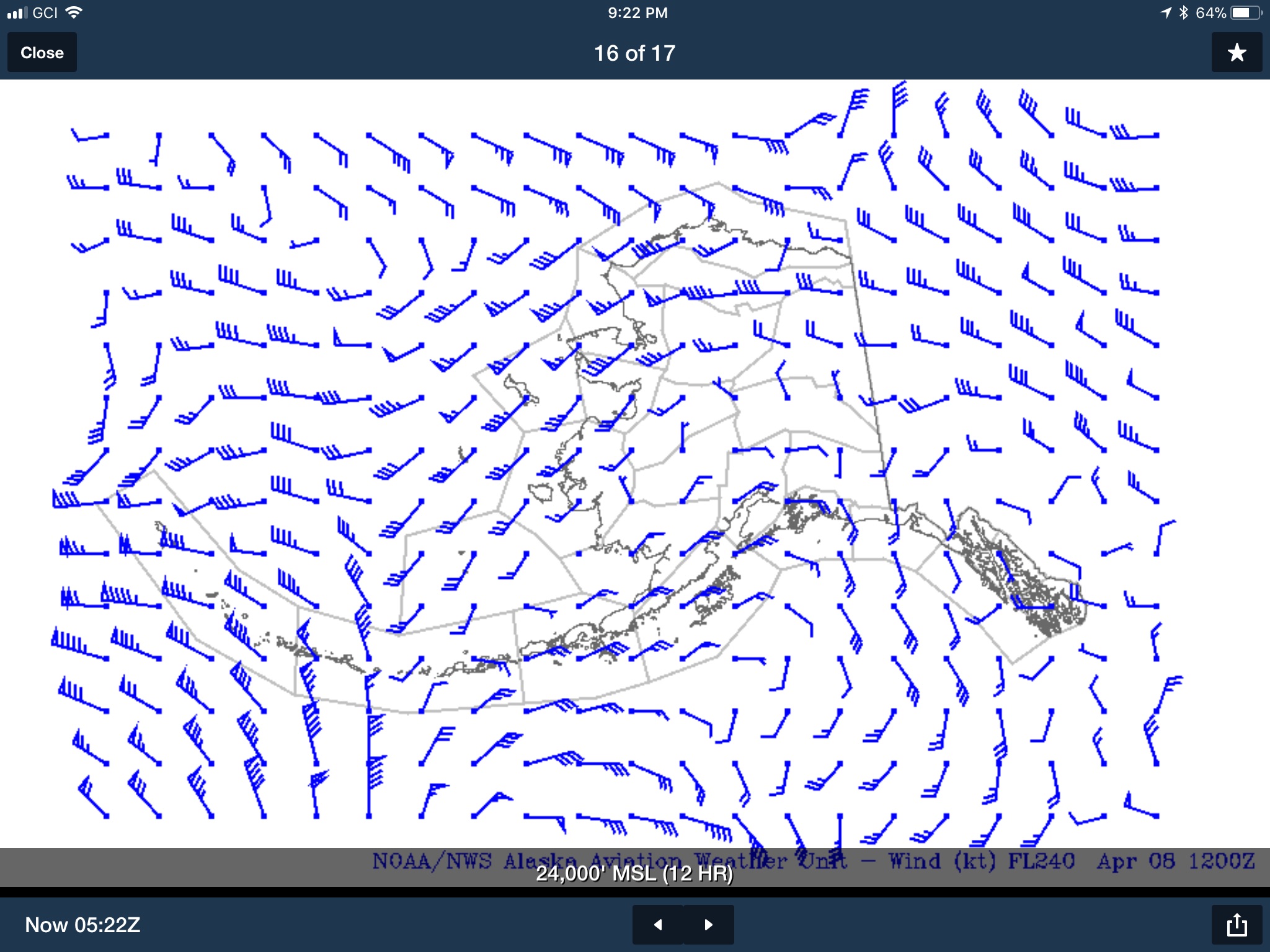

So with that context in hand, I wish this weekend’s story could have begun with a dare made while telling fish stories around an ice-fishing hole in sight of Denali and ended with the best map ever made of it the next day, kind of like the story of the Sourdough’s first ascent of the scenic north summit of Denali. But really, it was idle pilot chatter about Denali-flying while trying not to catch more fish that led to that map. Last Saturday I spent an hour flying in full view of Denali to that lake without a trace of wind, then a few hours talking about flying over Denali, and then another hour back to Fairbanks in view of it, and it all really got me thinking. It would still be months before I got my own license and the best weather for mapping it is in spring. All I really needed was someone with the right license to tag along with me, or some meat-in-the-seat as its known around fishing holes. But coordinating with other people is always a challenge. Plus I hadn’t worked out an oxygen system that could handle multiple people for very long, and for that matter I had never flown above about 12,000′ before, except for a brief test, so I really had no idea how well the plane would actually perform at 24,000′. But when I got home I checked the weather forecast, which predicted nearly calm winds all around Denali from 18,000′ to 25,000′, perfect for mapping, and given that happens so rarely and given how much Denali was on my mind I felt I could not pass up the opportunity. Normally Kristin’s schedule is opposite to mine so we rarely can fly together, but this Sunday was different. So I asked whether she and Turner would rather clean the house tomorrow or map the tallest mountain in North America…

The last weekend I was here, I found 10 other planes already fishing, too crowded by Alaskan standards. The word apparently got out, so this Saturday nobody showed up except my friends and I.

None of us wanted more than one fish, so we spent a lot of that time talking about flying around Denali while pretending to fish — it was just too beautiful of a day to leave early.

When I got home, this was the forecast at 24,000′, about the altitude we would map at. Imagine the blue things are arrows, they get fired in the direction the wind is going and the number of feathers denote wind speed. Around Denali, wind speeds were predicted to only be 5-10 mph, which is as good as it gets there.

Just because the trip was on a whim doesn’t mean we dont take safety seriously. Kristin has more than 10,000 hours flying in Alaskan IFR conditions and we both have spent most of our adult lives involved with field work in polar regions. So, while our goal was to map Denali, really we headed off for a systems shakedown. The main goal was to see how high the airplane could comfortably fly, fly around like that to make sure it was happy about being there, check our oxygen system to ensure it worked and see how long it lasted, make sure the fodar system didn’t get altitude sickness, and give me some training for my next license. But… a comfortable climb to 23,000′ would take a hundred miles and it just so happened that Denali is about 100 miles away, so… we also planned this as a shakedown of flying over Denali as well. Of course I preplanned a number of lines for this part of the test so we could map a few square miles around the peak so that we could determine it’s height. So the plane was an unknown, I was an unknown at this altitude, the oxygen system was an unknown, the mapping system was an unknown, and there were possibly other unknowns as yet unknown. For example, I had planned the oxygen system for me to spend about 4 hours at 23,000′, but now there were three of us and I was just guessing at the 4 hours anyway, so we set our limits on variables like these and made our contingency plans, then headed out for what we hoped was a very successful shakedown.

Charts like these are useful when comparing systems to each other, but whether those numbers could actually be trusted in flight was something we needed to explore.

Fortunately the trip to the mountain went more or less as planned. It was past noon by the time we were loaded and ready, despite a busy morning of preparations. Once loaded and fueled, we stumped our briefer for a while with our unusual flight plan, then headed off. A few hundred feet above the ground, we could see that our target was out in its full glory. We made a beeline for it, climbing a steady 500 feet per minute most of the way. The engine seem to be quite comfortable carrying three passengers and full fuel up, up, and away at that rate. It also gave us time to test our oxygen supply. I brought along a pulse-oximeter too, a small electronic device that measures your heart rate and blood’s oxygen saturation, all through your fingertip. By the time we hit 14,000′ we were all breathing this supplemental oxygen and every few thousand feet up we checked to make its flow rate was correct by clamping this little unit to our fingertips. Soon enough we were up to 23,000′ and within the airspace we given to play with around the mountain. And it wasn’t long after that I was starting to line up with my first mapping line over the peak! Years of day dreaming were about to come true!

It was clear and a million on Sunday.

I was a little tense — flying IFR for the first time, managing oxygen for three for the first time, flying over 12,000′ feet for the first time, flying over the most inhospitable terrain in the country at 23,000′ for the first time, and trying to manage a mapping system created a high mental workload and high diamond-making potential.

That first pass was the scariest. There was almost no wind at our level, but there was a breeze below us, and with a mountain this size you really have no idea what kind of turbulence you can expect, especially since there was prediction of turbulence 3000′ above us. I don’t know what’s really possible, but in my mind what was possible was the wings getting ripped off without warning. In any case, that first pass extended about 5 miles on either side of the peak without so much as a burble, so once some blood returned to my knuckles I began focusing on the mapping.

For mapping I planned four blocks of five lines each, with each block rotated by 45 degree to cover the cardinal compass directions. My idea here was that if the wind or turbulence was giving us issues on any one side of the mountain, we could chose the flight lines that avoided that area while still getting us over the peak. Given that the first North-South flight line gave us no grief, we kept on with those. The oxygen bottle was already half empty, so it was time to focus and get efficient. Things went well until the 4th line of the first block, when the GPS I use for following my lines freaked out. The plane wasn’t fully set up for mapping yet as it spent most of the winter without an engine, and I only got it back a few weeks ago and was still getting to the list of minor improvements from last fall. In this case, I had moved one of my portable GPS to a new location, but hadn’t yet run the line for the external antenna, so it was relying on a stub antenna that was easily shaded from satellite reception by the airplane itself. And for whatever reason on that last line, it lost track of itself and I no longer had a flight line to follow as I was still in the turn. Then the whole fodar system freaked out. Then weather started deteriorating. Then the oxygen was getting close to the descend-immediately limit. So it all went to hell at once. But we were so close and up until then things were working so well, I wanted to eek out as much data as I could as who knows when I would be back again. The fodar system sorted itself out quickly once it got untangled from the oxygen lines, we confirmed we were all still oxygenated, and eventually the GPS located itself again, but this burned up probably 10 valuable minutes of air. I was able to get two more orthogonal lines again before the turbulence above us sank into our level, and about this same time we were nearly out of oxygen so we called it a wrap and let Center know we were headed home. The trip home was uneventful, though I do remember as we turned towards Fairbanks still at altitude shouting something to Kristin to the effect of “Fuck what the controller wants, we need to descend NOW!” as I watched the oxygen needle move into the red. It remained to be seen how the mapping results would turn out, but the shakedown itself was a tremendous success and once we began our descent towards home I felt the tension leave my body as the realization of what we had just accomplish began to sink in — we just mapped the tallest mountain in North America! On a whim! And lived to tell the tale!

Even looking down on it, it is still an impressive mountain. I got yelled out for deviating off my course to take that photo, but it was worth it I think.

A pinnacle of achievement for many climbers is standing on that peak. For me, it was sitting 2000′ above it, operating a camera…

This is no place for field work.

Glaciers are cool.

Note the blue ice, where wind scours the snow pack away.

We operated in between the peak and that cloud in the upper right. Eventually that cloud came down and scared us away, just about when we were out of oxygen anyway.

I felt like I knew exactly how this guy felt… Even now, a few days later, I catch myself looking at the data and going “Holy Fuck! I’m looking at the best map of Denali ever made! And I made it!”

Twenty-two thousand feet in the air in a Cessna bush plane?! Who’s idea was THAT?

Not just meat-in-the-seat.

Slightly less tense…

Once we returned to Fairbanks, I immediately downloaded the data and found that it indeed all recorded correctly and would be suitable for processing. Then we went out for dinner to celebrate. And we all had something to celebrate. For Turner, there are no other 12 year old homeschooled kids on the planet that can say for their Geography class they were part of an expedition to definitively measure the height and shape of the tallest mountain in North America. For Kristin, there are likely no other women alive that can say they survived flying back and forth over the tallest mountain in North America with her cranky ex-husband in a 50 year old plane that didn’t even have an engine three weeks ago. For me, I may not live in a house that has running water or even bedrooms, I may not drive a car that has been cleaned in 20 years, but I do have a family that puts up with my quirks and supports my dreams. And Holy Shit, we just mapped Denali!

Shakedown successful — the digital equivalent of a 14′ spruce pole in Denali’s north peak. I don’t care what anybody says, the sourdough crew will always be the first to have climbed Denali in my book. You can learn more about what we’ve learned so far from these data here.

Shakedown successful — the digital equivalent of a 14′ spruce pole in Denali’s north peak. I don’t care what anybody says, the sourdough crew will always be the first to have climbed Denali in my book. You can learn more about what we’ve learned so far from these data here.

Toasting ourselves and the 1910 sourdoughs almost exactly 108 years later.

I just created a Facebook page for Fairbanks Fodar. Please like it to keep up on the latest news!