1002 Mapping Nearly Complete!

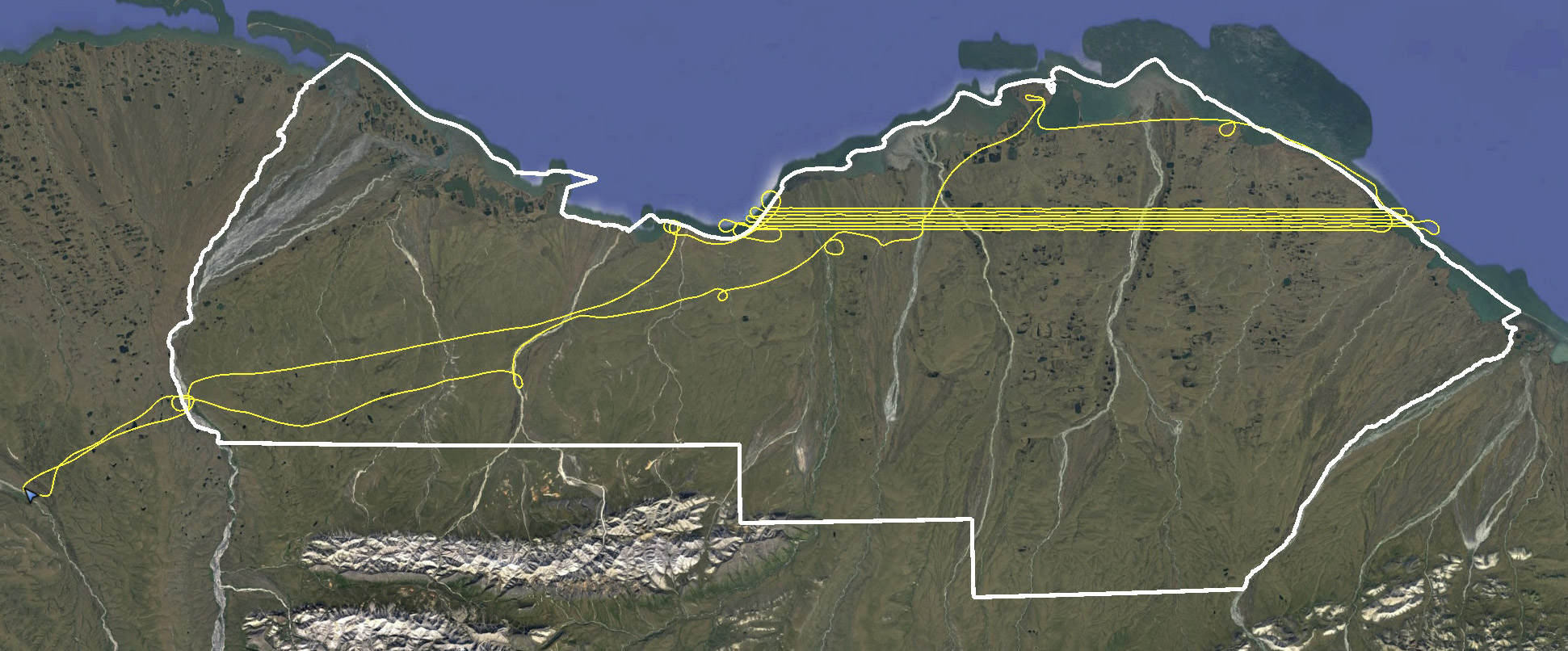

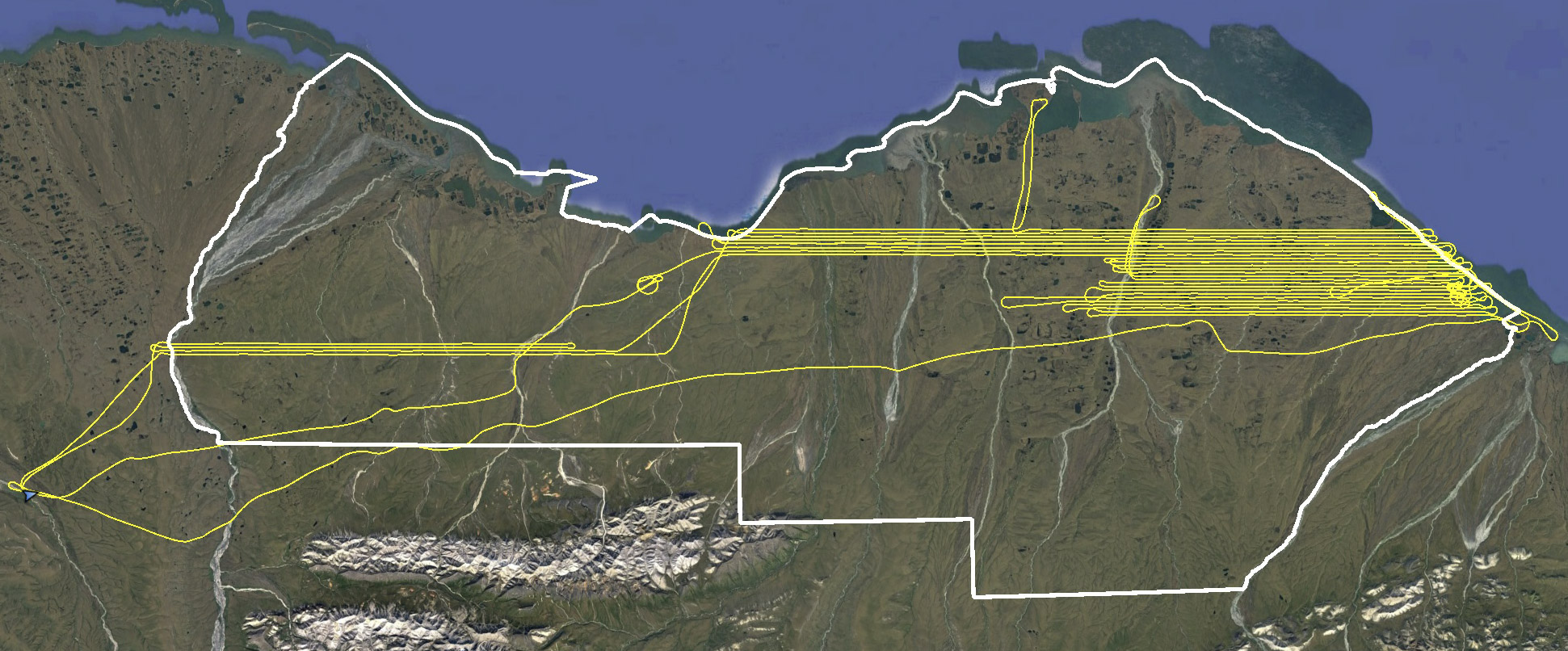

In a little over a month after my first flight, I’ve now completed about 95% of acquisitions of the best topographic map ever made of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s 1002 Area, flying over 150 hours and taking over 150,000 vertical photos.

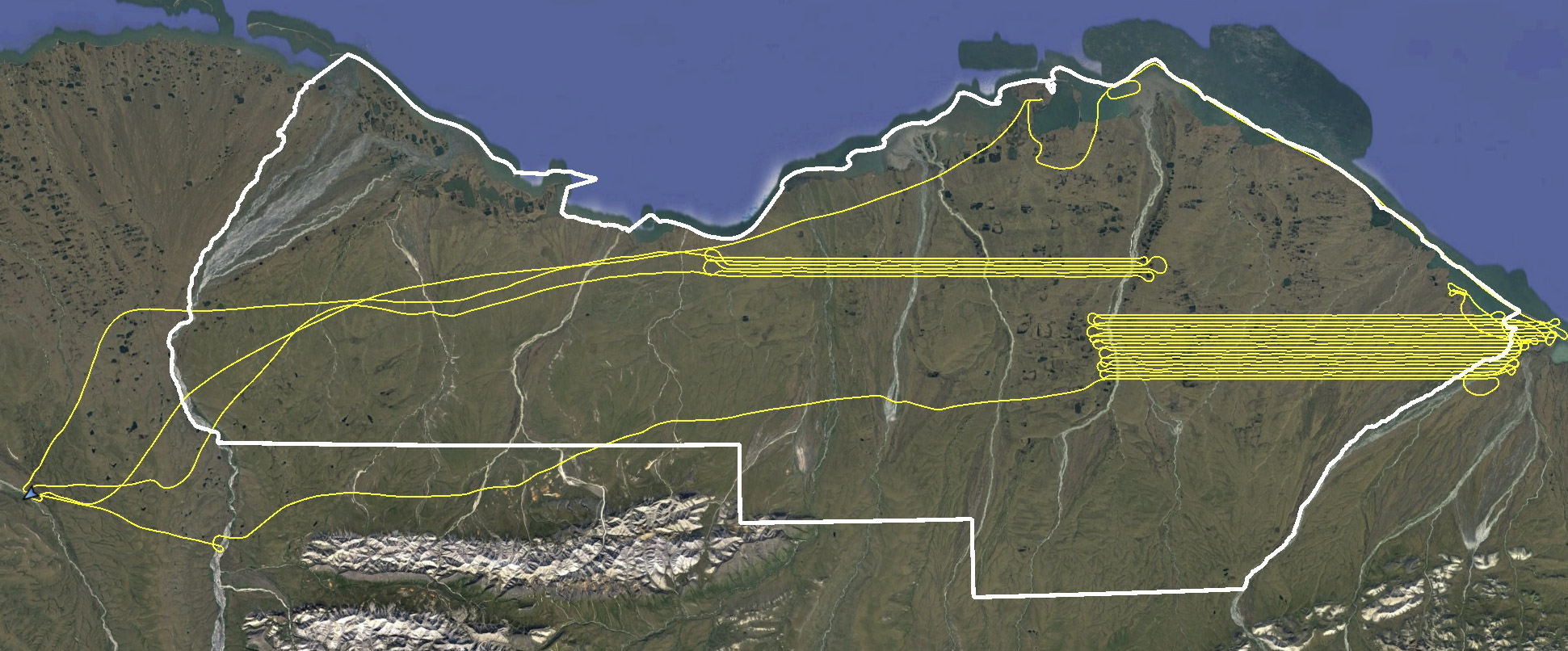

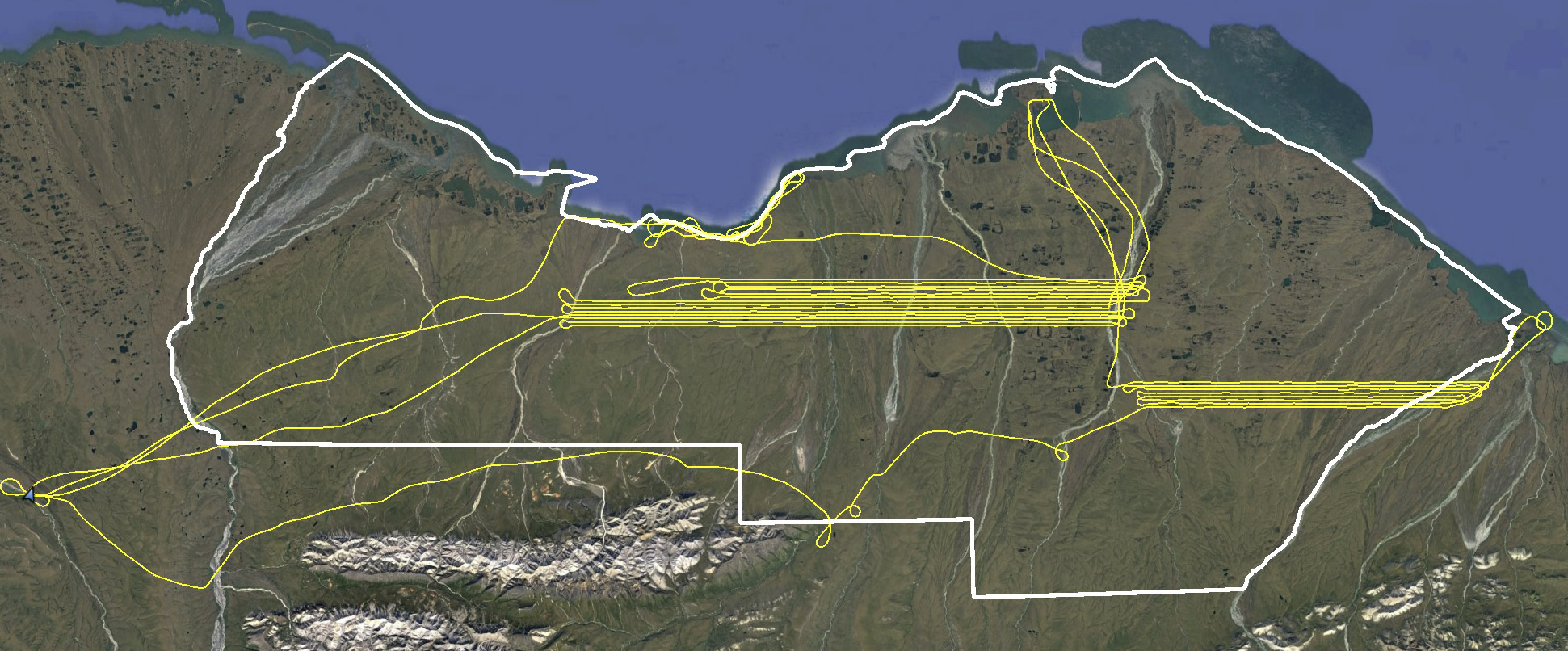

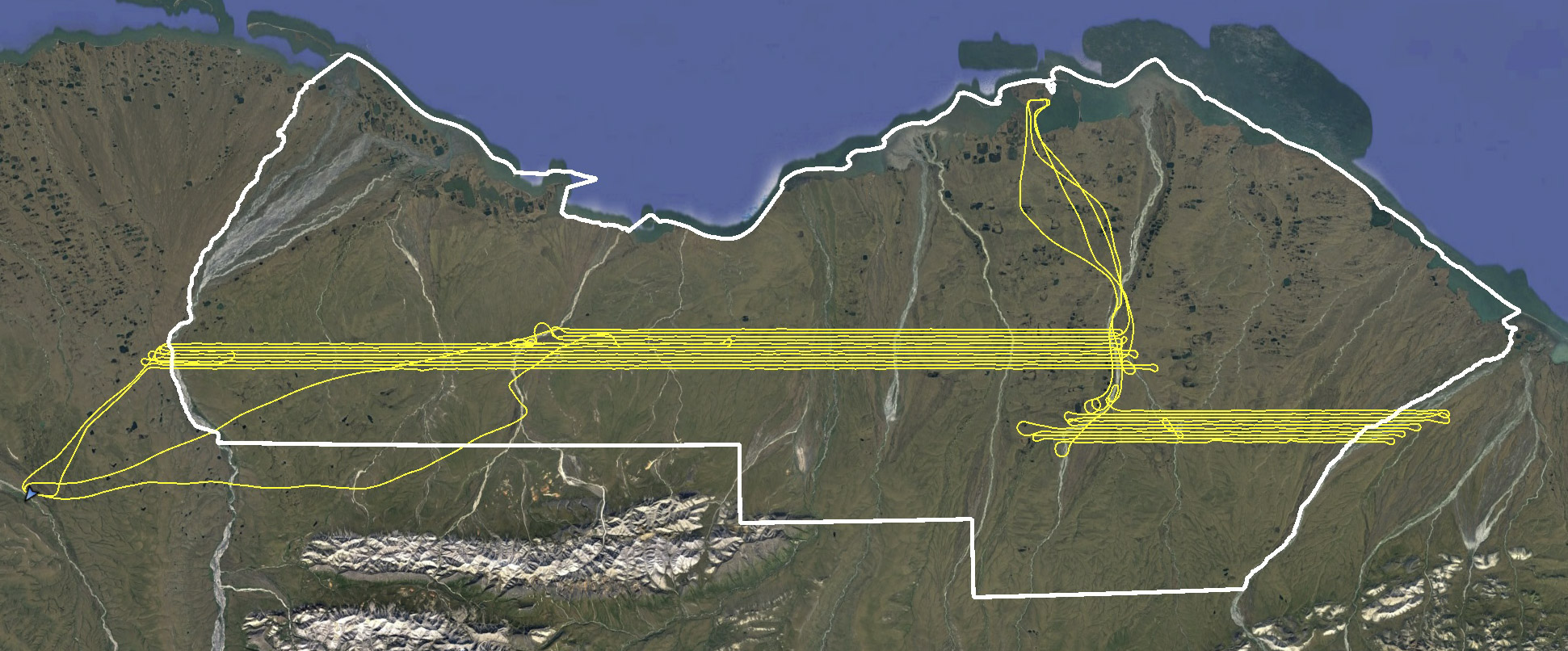

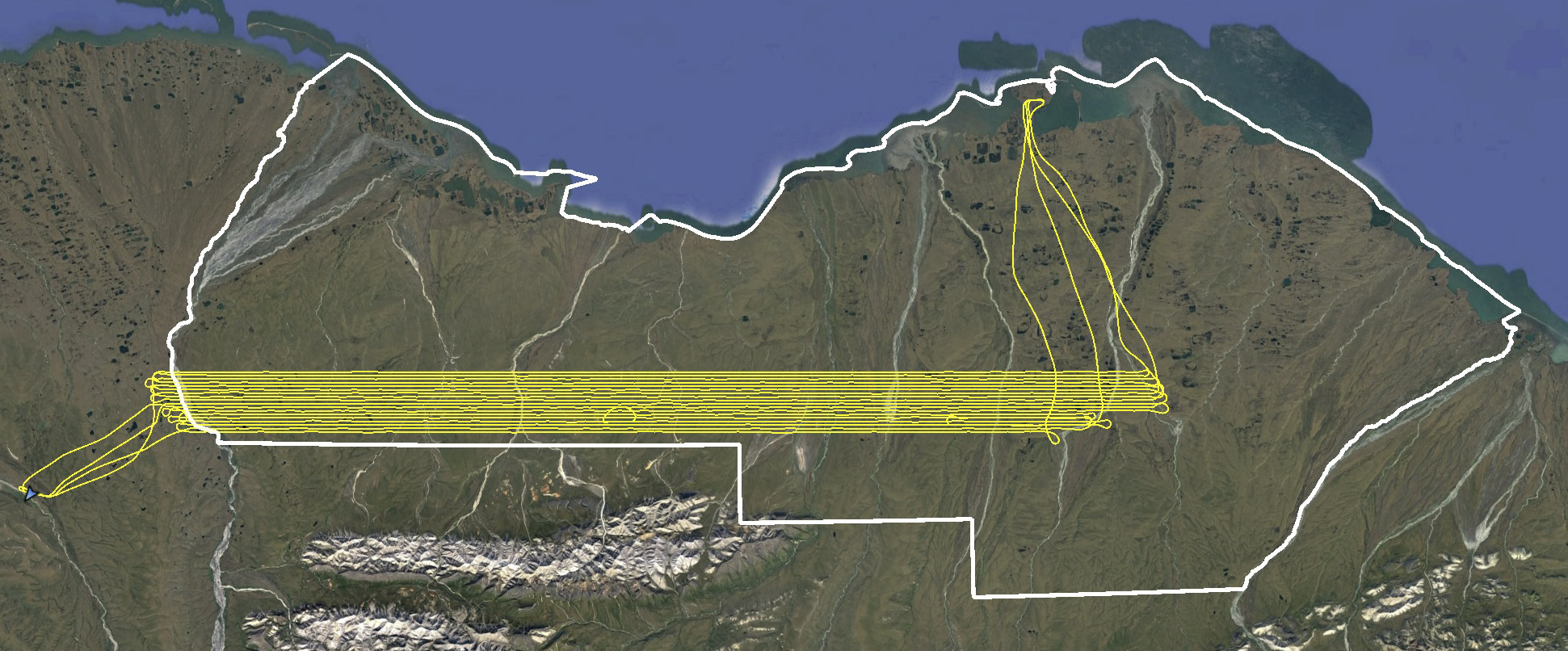

The yellow lines are my flight lines, the white outline is what I’m trying to fill. I’ve already mapped the islands in the north in previous years, so I’m saving those until the end in case I run out of time. The area to the south and a few fill-in lines should take less than a day to complete.

My first acquisitions began on 24 June, and I described the first two weeks of acquisitions here. During all this time I stayed at Kavik River Camp, due to it’s proximity to the 1002, fuel availability, and good company. I returned to Fairbanks twice during this time to see my son act in plays he participated in with the Fairbanks Shakespeare Theater, but on my return I was committed to staying in Kavik until I was nearly complete with acquisitions. The weather here is notoriously poor and this summer was no exception. It was a late spring, I had been prepared to start several weeks earlier, and summer was largely a mixture of rain, snow and fog with a smattering of hot days. So my main goal was to finish before winter set in.

I returned on 12 July 18, flying direct to Kavik in only 3 hours. I decided to fly over the top of the clouds on the way in over the mountains, as they were pretty broken and had a good ceiling underneath, until I reached the north side where they coalesced and began raining underneath. Fortunately I knew that Kavik was in the clear, and before long I was descending from 12,000′ nearly directly over it… Once on the ground I dumped out my extraneous gear, fueled up, and headed out to map!

I’m on the hippy plan at kavik — sleeping in my own tent and mostly eating my own food.

I’m on the hippy plan at kavik — sleeping in my own tent and mostly eating my own food.

My goal in the short term was to finish as much as I could near the coast whenever the weather was good there, so that I would have the inland areas to work on the rest of the time. I also tried as much as possible not to skip over any areas, to minimize the temporal changes between adjacent flight lines, and generally speaking that worked pretty well up until the last day, in the southernmost region.

The weather held the next day and I launched at 5:30AM for a great day of flying over 13 hours. I was able to finish from the bottom of Camden Bay all the way to the west coast, with my lines almost reaching the Aichillik River, which forms the eastern boundary of the Refuge. A few more lines there and I would be done with the entire coast!

I love this spot, an old DEW line site just north of the Aichillik River.

You can easily walk to the beach here, or bring a small boat and float across the lagoons to visit the barrier islands.

Lot’s stuff like this growing around too.

The weather held one more day, giving me a chance to fly another 10 hours, completing the eastern boundary up and away from the coast — I was now finished with the coastal regions!

The weather next three days, 15-17 July, were pretty marginal for mapping. It gave me the chance, however, to spend some time analyzing my photos and system. I had noticed that my photos were not as sharp as they normally were earlier, but was too busy flying to fully troubleshoot. But it was driving me nuts trying to sort it out. They were fine for mapping, but not as sharp as they should be, and after spending all this time and money acquiring them I of course wanted them to be as good as possible. One possibility was that it was my propeller. Taxiing around on soft, loose rocks around Kavik had beat the hell out of my prop the past two weeks. Fortunately a file and a rebalance solved the issue, twice, or so I thought. I stopped taxiing on the ramp and back taxiing on the runway to keep it from happening a third time, so I knew at this point it was not my prop. I tested and retested the camera on the ground and all was fine. During the bad weather days I took some local test flights trying all combinations of cameras and lenses I had with no luck, it all looked fine. I was getting a little extra oil on the camera glass due to changing the oil last time, but this was gone by now. I also changed the camera port glass thinking it had perhaps worn out with scratches. But the problem was intermittent. So I began playing with power settings in the engine to see if it was a vibration or harmonic, using an app on my phone to measure it while I flew. But nothing seemed to work and I was coming to the conclusion that it was an intermittent clusterfuck, the most difficult to solve. And trying to do all this while flying 10 or more hours a day, backing up data, working in a tent, etc was quite a chore. So after a week of throwing the best of my brain against this problem I was still stumped.

I come out to the letters to do system testing because they make a nice target and are close to camp. They’re also fun to think about. Someone put a lot of care into making them.

The weather improved on the 18th and soon enough the problem reappeared again. I had launched at 5AM, and spent quite a bit of time flying around along the coast trying to sort it out. The coast was the only place I could do this because that’s the only place there are sharp, linear features to test focus against– driftwood. I finally determined that my lens was fucked, somehow it wasn’t holding focus in the air. When I stopped down I could get it to sharpen up a bit, but at my normal aperture it was no longer fully sharp. So I landed at Barter and swapped lenses and all was fine after that. I flew another 11 hours back and forth that day, filling in the infield considerably and happy once again to have my brain back so that I could focus more on the landscape.

The 19th was another down weather day but on the 20th I was able to slog out another 12 hour day of lines spanning the full width of the 1002. Now with the system working at 100% I was able to have a really good look at how the landscape varies across its width. Each watershed here is unique. To the west, where the Sadlerochit Mountains push to within 20 miles of the coast, the watersheds are steep, lumpy and rocky. The east, here it really struck me how little the rivers I’m most familiar with have to do with the main part of the landscape. The main rivers drain water from the mountains, not the 1002 Area. Part of the reason for this is that the landscape here is not shaped by river, but rather by tectonics — what we think of as a coastal plain is more properly thought of as a carpet that’s been pushed forward, creating sine waves of hills and rills which trap water and push rivers around them. Google Earth really doesn’t have the resolution to see this clearly, but anyone who has been on either side of the Jago River has seen the large hills south of the mountains and must have wondered how they got there, as it certainly is not deposits from the rivers far below them. The reason those lakes are there is because of this tectonic folding, otherwise it would likely look just like the area in front of the Sadlerochit Mountains with no lakes at all, just steep watersheds. The lakes themselves sit in what seem to be little perches, with one draining into another. I also noticed very few pingos in the drained lake basins, and wondering if it’s due to with the proximity of rock below the surface (or conversely the lack of waterlogged dirt beneath it). Such an interesting area, and I know my map will add tremendous value to anyone trying to sort out how this place came to be and what makes it tick.

Though the 1002 Area is often referred to as a coastal plain, I don’t think that’s an accurate description.

Though the 1002 Area is often referred to as a coastal plain, I don’t think that’s an accurate description.

Does this look like a coastal plain? Each small watershed here is unique, and they can hardly be lumped into the same functional description.

Does this look like a coastal plain? Each small watershed here is unique, and they can hardly be lumped into the same functional description.

Here the landscape is shaping the rivers more than the rivers are shaping the landscape.

The big rivers are the most obvious feature of the 1002 landscape, but my feeling is now that they are just tourists passing through, as these rivers drain the mountain watersheds not the tundra watersheds.

The big rivers are the most obvious feature of the 1002 landscape, but my feeling is now that they are just tourists passing through, as these rivers drain the mountain watersheds not the tundra watersheds.

I’d really like to explore more around here.

My favorite glacier is peaking out near the center of the frame. I’ve spent many, many nights camped on that glacier…

I had been living in the same clothes for the past week, so I made the mistake of trying to wash them. I had never washed clothes in the field before, but being around a roomful of geologists taking showers almost every day was making me feel uncharacteristically self-conscious. I didnt really have a change of clothes, so I put on my sweat pants and nomex sweater and threw everything else into the washer. Then I made the bold move of taking a shower. At just about the time I soaped up my hair, the generator failed. The water pressure held long enough for me to get the soap out of my hair, but my flying clothes were still in the soak cycle. Apparently it was a major engine failure and my clothes were at risk of never getting dry in this wet, cold Arctic summer. So I went to bed wondering about how I could build a solar oven.

Fortunately by morning a backup generator had been brought online and my clothes were ready by about 9 AM. I had written off the day already thinking I’d be spending it arranging visquene and sheet metal in parabolic shapes, so I decided to spend the day mapping to the west on some commercial projects I had lined up.

I think when most people think of the 1002 Area or the coastal plain they are thinking of something that looks like this — super flat and covered by lakes. The 1002 Area looks nothing like this, anywhere.

I think when most people think of the 1002 Area or the coastal plain they are thinking of something that looks like this — super flat and covered by lakes. The 1002 Area looks nothing like this, anywhere.

I think also when people think of drilling within the Refuge they are imaging something that looks like this will be built. I’m no expert in these things, but there’s no need for another Deadhorse. Barter Island might get built up a bit, but it’s already so trashed from 50 years of neglect that the oil industry moving in would be an improvement, literally.

The fun really started the next day, on the 22nd. The weather was good enough, so I launched at 5:30AM and flew a total of 14 hours, nearly all of it mapping as my lines were now only 10 minutes from Kavik. It felt like such a great opportunity, travelling back and forth between the Canning and Jago Rivers all day long, imaging how the landscape formed, what processes were at work that continued to shape it, and of course getting closer and closer to my glaciers in the mountains. I had never seen them from some of the angles along my flight lines and it was such a treat to get know them better and look forward to my visit in the not too distant future.

The view from the cheap seats.

Though the weather was predicted to be poor for mapping the next day, I poked my nose into the area to find it beautiful. I was now focused on the southern notch to the east of the Sadlerochits. A small puffball was forming over the Sadlerochits, which I watch grow throughout the morning into a small cumulonimbus cell. I didn’t think much of it, as it was beautiful where I was to the east and it seemed contained to the mountains. I flew back past it to Kavik about noon to refuel, then headed back to continue mapping. A few hours later it had grown considerably and started to rain there, so I left my beautiful sunny skies to the east to head back before it closed me off. I took a few photos as I flew by and even started up my 360 dash camera to capture its beauty, only to discover that hidden behind it was a wall of nastiness. The ceiling dropped down to under 500 feet and a ground fog was creeping up from the coast. I continued through the narrowing wedge of clear visibility, keeping an eye on the escape routes behind me. Fortunately there was no lightening, but I’m really glad I spent some time in good weather checking out all of the gravel strips I knew about en route for eventualities like these. Fortunately the Canning River was relatively open and I could see the light at the end of my tunnel. As I passed into it and up over the moraine, the ceiling came down again and it began raining heavily. Dave the helicopter pilot asked me how things were back in the direction I had come as he had some geologists out there and I gave him the bad news, as I attempted to land at Kavik by feel. Those guys didnt get back until after 10PM I think, and already set up a tent hours before. All in all it was a productive 9 hour day that ended at 3PM for me, but it gave me the chance to spend the rest of day downloading camera cards, gps units, backing up data, and chatting with geologists.

Such a pretty cloud. It was his buddies that were the problem…

Over the course of the month I learned a lot about the geology of the 1002 Area, thanks to some great conversations with the geologists living there and overhearing tons more.

I was the odd man out, in many ways… It also might seem ironic that here I am trying to map the Refuge to deter damage from 3D seismic data collection while living with a bunch of geologists using 3D seismic data to understand the geology out here. But in the end we’re all just scientists studying one thing or another, how others use that data is their problem not ours.

At this point I had calculated that I was almost within range of finishing in one long day. Unfortunately with the dynamics of the day before I didnt get to bed until nearly midnight and needed to catch up on some sleep and the weather was still a bit unsettled, so it was nearly 11AM by the time I launched. I was able to sneak in an 8 hour day of flying, but it was not quite enough finish. The fog had not quite receded from the night before, so I skipped some lines to work further inland until it flushed out, then picked up where I left off. I have a rule that the second time I forget to turn the camera on while flying it’s time to go home so even though there was enough daylight to squeeze in another hour or two and connect with the lines I did in the morning, I decided to bail and head back for some sleep.

I had to work my way around the fog until it burned off after noon.

Fortunately the next day was marginal weather and I spent it backing up data and sorting gear. I decided to head back to Fairbanks on the next day, unless we got some perfect weather. I had just put 100 hours on the airplane in less than 2 weeks and it needed a little TLC that was much easier to give in Fairbanks, as did I. And I head amazingly reach my goal of getting within a day’s work. To truly complete the project, I needed to do a more in depth processing of the data to figure out whether there were any gaps I missed, and that is a process much easier to do in an office than a tent. So I sorted and packed and prepped and chatted and caught up on sleep.

Thursday the 26th did not turn out to be a perfect day, but it seemed like I might be able to sneak a few hours of mapping in before heading home by launching before 6AM. I tested the system just after take-off like I normally do and all seemed fine, but by the time I reached the Canning River my photos were just a ball of blur. I’m not sure if it was the small squall I flew through or some condensation inside the belly, but I had to turn around and land and clean the glass. By the time I got going again and avoided the squalls this time, it appeared that my area was under some dark clouds that threatened rain. Plus it was starting to get late in the morning and I had a serious case of get-home-itis at this point. So since I was down near the coast anyway I swung over the Pt Thompson to see how the seismic lines looked that I mapped about a month earlier. Unfortunately they were still there, so I tried to map them by eye. But you can read all about that here.

The coast was clear enough to do some mapping over the 2018 seismic survey lines, but the mountains weren’t as conducive — time to head home!

So overall it’s been a great month for this project. I’ve got to switch gears for a while get my glacier field work in the mountains behind the 1002 done, but then I’ll be back to finish it off! Below are some sample vertical photos, pulled somewhat at random, to give a sense of what the final result will look like; each non-cropped photo is about 1 km wide. Everything feature you see in these photos will appear in the topography.

This is a 100% crop of the previous image.

This is a 100% crop of the previous image.

This is a 100% crop of the previous image.

This is a 300% crop from the original.

This is a 100% crop of the previous image. The resulting map will include tussock topography here.