An Alien in the Okavango

Text and photos by Turner Nolan

After my first mission to Earth my superiors thought that it was so interesting and successful that I was asked to return! And this time to the opposite side of the planet from the Arctic! My objective this time was to learn about ecology on a continent called Africa — to gain an understanding of how the human and non-human creatures here relate to their habitat. So once again I was transported into the body of a 13 year old earth human, this time accompanying the Papa to a land called Botswana.

On this assignment I learned numerous things but the most interesting to me is what the humans call an ecosystem. On the first few days I kept hearing the human adults use the word “ecosystem” but couldn’t quite understand what it meant. I asked the Papa to explain it to me, but even after he explained to me it still took me sometime to exactly understand what an ecosystem was, but now I think I understand. I believe ecosystems are the connections that bind everything in a natural area to each other, like how carnivores, herbivores, and vegetation coexist but altering that balance can create new ecosystems, new landscapes, and even change the climate of the planet.

One thing I learned about all ecosystems is that they each have keystone species. Now I believe a keystone species to be an animal that has an irreplaceable importance on it’s ecosystem, like our gifkins on the white beaches of Fey. If you still don’t understand, think of it like this: our Gifkins only eat flim trees, not letting grow above Gifkin mouth height, such that the Notrey birds can’t safely nest there because they might get eaten by the Zergos, which leaves the beaches full of Tiphems to burrow in the trees safe from the notreys, all because of the Gifkins, making the Gifkins a keystone species. After I arrived in the savanna just north of the Okavango Delta in Botswana (Earth Date: November 3, 2018), I started looking out for ecological connections between species that might indicate which was the keystone species.

After a few days I realized the keystone species in this region is the elephant, because of their control on the forests and grasslands and thus the population of other species. Elephant habitat in northern Botswana is primarily swamps and savanna. This report is mostly about savanna. Savannas are like grasslands, but grasslands don’t have trees like savannas do. Savannas are like forests, but forests have closed canopies whereas savannas mostly do not. Elephants keep the savanna from becoming forests by eating lots of the trees, knocking them over, and pulling out their seedlings. But they don’t do this to all the trees, so a stable population of elephants will maintain a stable mixture of grass and trees in the savanna.

Thinking about all the things elephant do to affect the ecosystem, I started to wonder what would happen if there were no more elephants…

If there were no more elephants… I think trees like these mopane would find it easier to survive because they would be able to grow into taller trees and become a closed canopied forest. They’d also be able to expand into new areas because there would be no elephants to eat the tasty saplings, and therefore start to shrink the grassland areas.

If there were no more elephants… I think grazing animals that eat the grasslands would find it harder to survive as their grassy habitat was displaced by forests.

If there were no more elephants… I think predators like these lions, cheetahs, and wild dogs would find it harder to survive because their prey, grass-grazing antelope, would be fewer in number and harder to find.

If there were no more elephants… I think scavengers like these hyenas, vultures and jackals would find it harder to survive because there would be less carrion created by predators.

If there were no more elephants… I think insects like termites and harvester ants would find it harder to survive because they have less grass to eat, and they could no longer reshape the land and recycle nutrients into the land as much as they do today.

If there were no more elephants… I think insectivores like these ground hornbills and cattle egrets would find it harder to survive because the habitat of the grass-dwelling insects they eat would be smaller.

If there were no more elephants, not all animals would find it harder to survive. The shrinking numbers of grass-loving animals, insects, and birds might be balanced by increasing numbers of forest-dwelling animals, insects and birds. So along with the changing habitats of the ecosystem, the biodiversity of the ecosystem would change too.

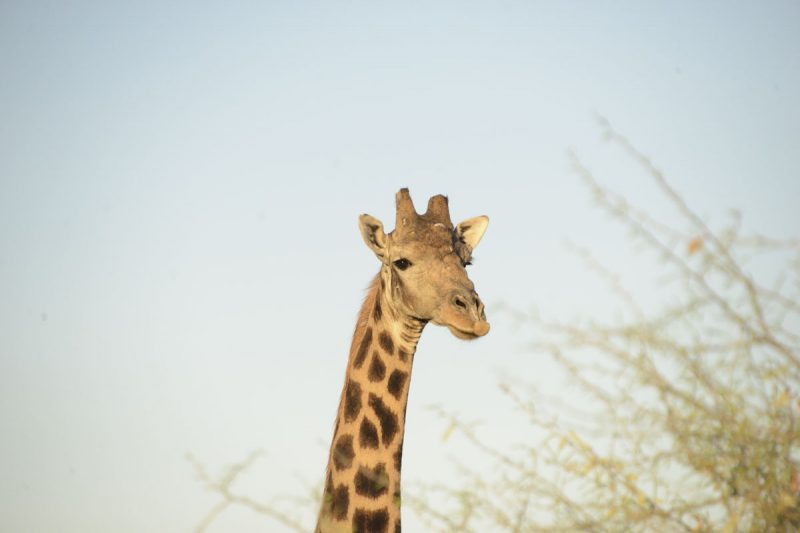

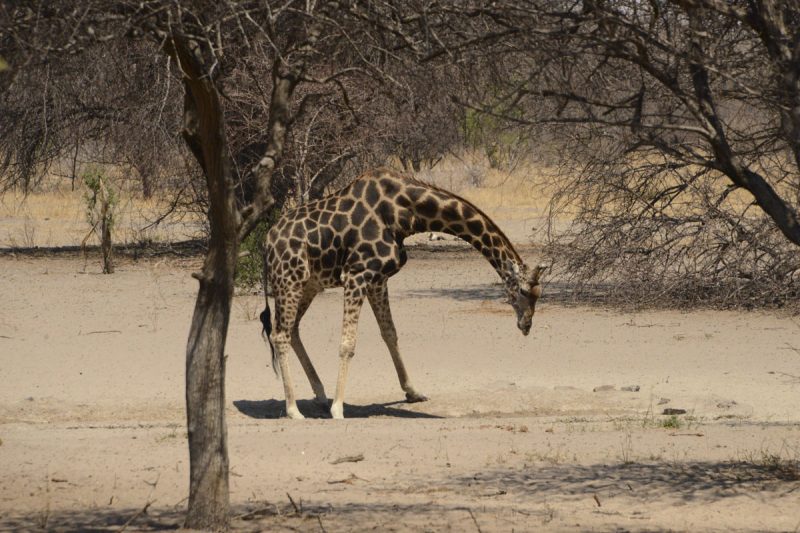

If there were no more elephants… I think browsers like these giraffe would find it easier to survive because there would be more tall trees creating the leaves that they eat.

If there were no more elephants… I think forest-dwelling birds would find it easier to survive because there would be more forest habitat providing branches for nests and forest insects for food.

If there were no more elephants… I think forest-dwelling creatures like these monkeys and baboons would have more forest habitat to live in, giving them more food and protection from predators so they could grow in numbers.

If there were no more elephants… I think ambush predators like these leopards would find it easier to survive because forests would provide them with more ambush opportunities.

If there were no more elephants… it would probably be due to humans. Some humans kill elephants to get their ivory tusks and other humans build cities and fences that destroy elephant habitat. Thus humans are also a keystone species here.

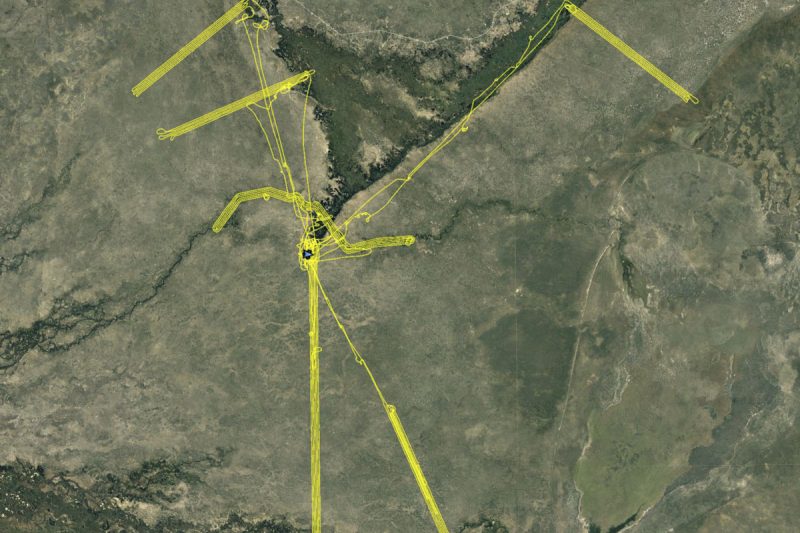

Fortunately there are still elephants. Lots of them. Maybe even too many. Too many can have the opposite affect on biodiversity – turning the savanna into mostly grassland. Unfortunately we do not know whether there are too many or too few elephants, but that’s what the Papa and I spent a month in Botswana studying. By tracking the changes to their habitats, we can learn how the biodiversity is changing. But’s that’s a story for another report…

Yet again my mission to earth is over, and yet again I’m amazed. This time I believe I learned more, like what ecosystems are, keystone species, and lots of different non-human organisms. But thing I take away the most is how important humans are to this planet, and how they as a keystone species of their planet can either destroy their natural world and it’s ecosystems or protect them. My final message to my people is to not make the same mistakes the humans have and to learn from their successes.

The End

PS. Click here to learn more about the research the Papa was doing.