Fairbanks Fodar Aids Rescue of Rare Talkeetnan Waterfoul

Turner and I spent a long weekend in Talkeetna, attending the 8th Annual Talkeetna Fly In, and used the opportunity to test some new fodar upgrades as well as participate in an opportunistic rescue in the foothills of Denali.

Technology continues to improve, and I try to keep up with the latest so that I can continue to make the best maps ever made of Alaska. This weekend I tested 3 survey-grade GPS receivers in the plane, a new camera, and a new way to link them all together, on our flights down there as well as during the competitions.

The Fly In was a great event — lot’s of pilots from around the state converging to talk about flying, participating in some friendly competitions, and exploring a cool area near Denali National Park and Preserve. The town of Talkeetna is a ten minute walk from the airport and only about a 10 minute walk from end to end. This time of year it felt like tourists outnumbered the locals, but still not all that crowded.

We arrived early on Friday, probably the first people there from out of town. The weather was pretty marginal on the way down, but thankfully not turbulent and we largely made it without issue. Once there we visited the friendly folks at Talkeetna Air Taxi, who told us after a week of bad weather they had shuttle 80 climbers onto Denali that morning in their 3 or 4 turbine otters and several beavers! Then we walked into town and just happened to eat in the restaurant that we had dinner at the night of our wedding’s rehearsal dinner, nearly 15 years ago. I guess there’s only 3 or 4 restaurants to choose from, so the odds were in that favor, but I had forgotten about that night until we sat down there. By the time we were done, I had already received a few texts from friends who had arrived, so we headed back to the airport to find a camping spot and settle in for the night.

We swung by Chena Marina as part of the Poker Run. For each airport you stop at and take a photo, you get an extra playing card (maximum 5), and the high hand gets a prize. It was a long day already for Turner, and he wasn’t sure whether what he was headed towards was worth staying awake for.

We stopped at Clear too, and saw one of the Civil Air Patrol’s gliders there. Turner wants to be a glider pilot.

We stopped at Clear too, and saw one of the Civil Air Patrol’s gliders there. Turner wants to be a glider pilot.

As far as anyone really knows, this could be the center of the Universe.

About 15 years ago, I had dinner in this very spot with a group of about 20 friends and family. The copious amounts of alcohol drank that night ultimately led to my current dinner partner.

First time in the airplane tent this year.

First time in the airplane tent this year.

The early arrivals on Friday.

Saturday was the main day for flying events. This year for the first time the main event was a gross weight STOL competition. Here everyone loads up their plane to its official maximum then tries to take-off and land in the shortest distance they can, with the winner having the lowest combined total out of two tries. So if you take-off in 300′ in one round and land in 200′ in another round, your score is 500′. The ‘normal’ version of this competition is to be as light as possible, so that means emptying out the plane and as much fuel as possible and not eating for a few days beforehand. While it’s a fun competition, it doesn’t really reflect the way most of us fly, which is stuffed with gear, and occasionally taking off from unimproved strips that are way too short. So we were all looking forward to learning something new!

A rival gang of aviators are chased off by the field marshal early in the morning.

Breakfast on the tail of the Pacer.

By mid-morning there was quite a crowd.

All of the competing planes need to get weighed to ensure they are loaded to their gross weight. Here Drew continues to get more of a workout than he hoped for while Shawn rigs the scales to lighten his load…

All of the competing planes need to get weighed to ensure they are loaded to their gross weight. Here Drew continues to get more of a workout than he hoped for while Shawn rigs the scales to lighten his load…

Me, taking off during the competition while an official tried to determine the exact spot where I lifted off. I think he was probably running faster than me at the time. I was one of four Cessna 170s in the competition, but I was the only one with a stock O-300 145hp engine, the others had 180-210 hp engines… Thanks to the photographer at Airframes Alaska for taking this great series of photos.

Me, taking off during the competition while an official tried to determine the exact spot where I lifted off. I think he was probably running faster than me at the time. I was one of four Cessna 170s in the competition, but I was the only one with a stock O-300 145hp engine, the others had 180-210 hp engines… Thanks to the photographer at Airframes Alaska for taking this great series of photos.

I had been planning to fly in the 206, but the week before this happened, when landing on gravel. I was glad to fly in the 170, but I stuck to the pavement for competition whereas everyone else used the gravel strip. One prop replacement per month is my limit…

I had been planning to fly in the 206, but the week before this happened, when landing on gravel. I was glad to fly in the 170, but I stuck to the pavement for competition whereas everyone else used the gravel strip. One prop replacement per month is my limit…

Here is a video I made by compiling all of the camera phone video I caught. Sorry I missed so many people! I think there is a lot to be learned by watching these.

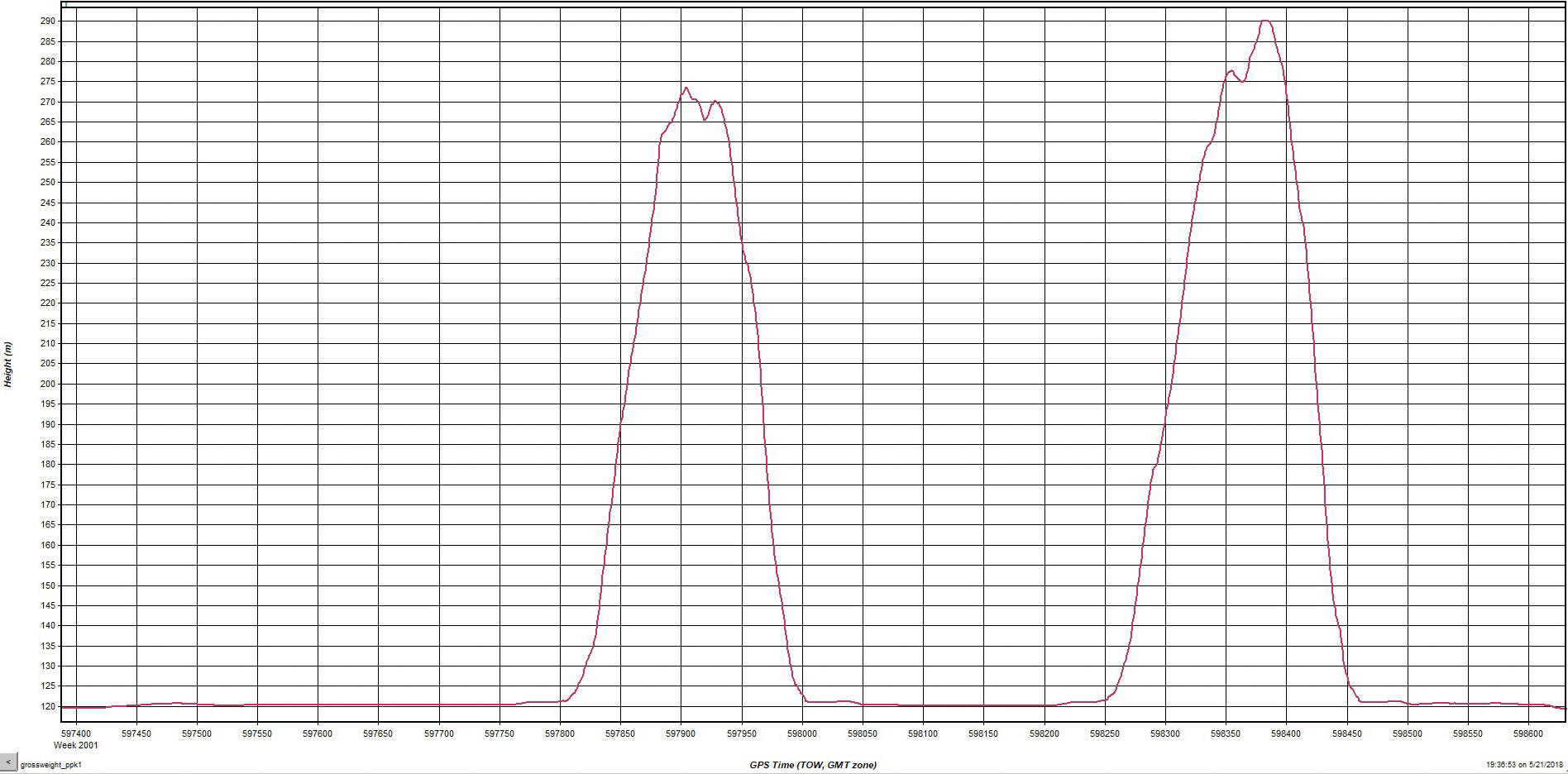

Having my mapping system installed in my plane allowed me to analyze my performance more than just a video alone can.

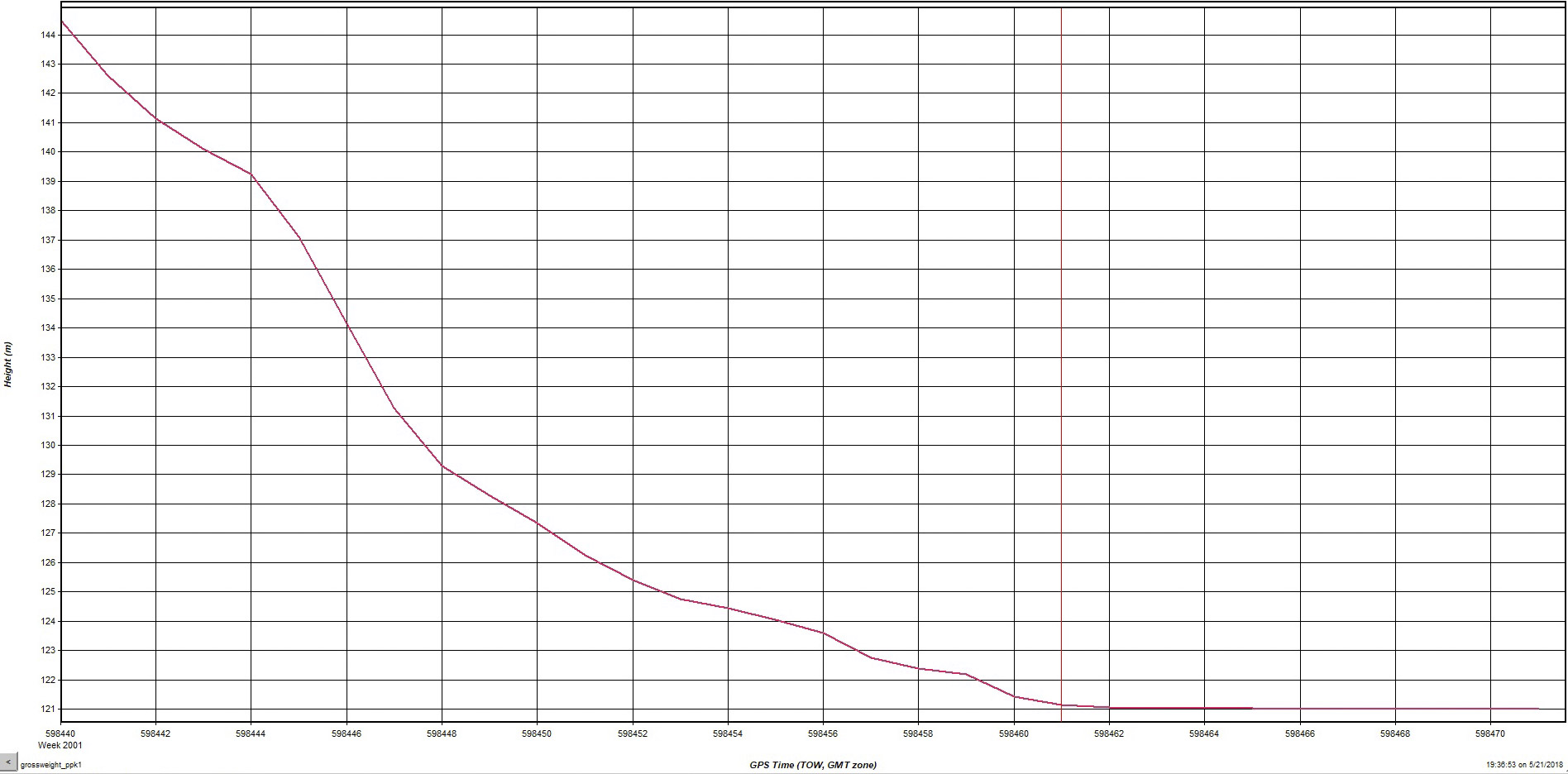

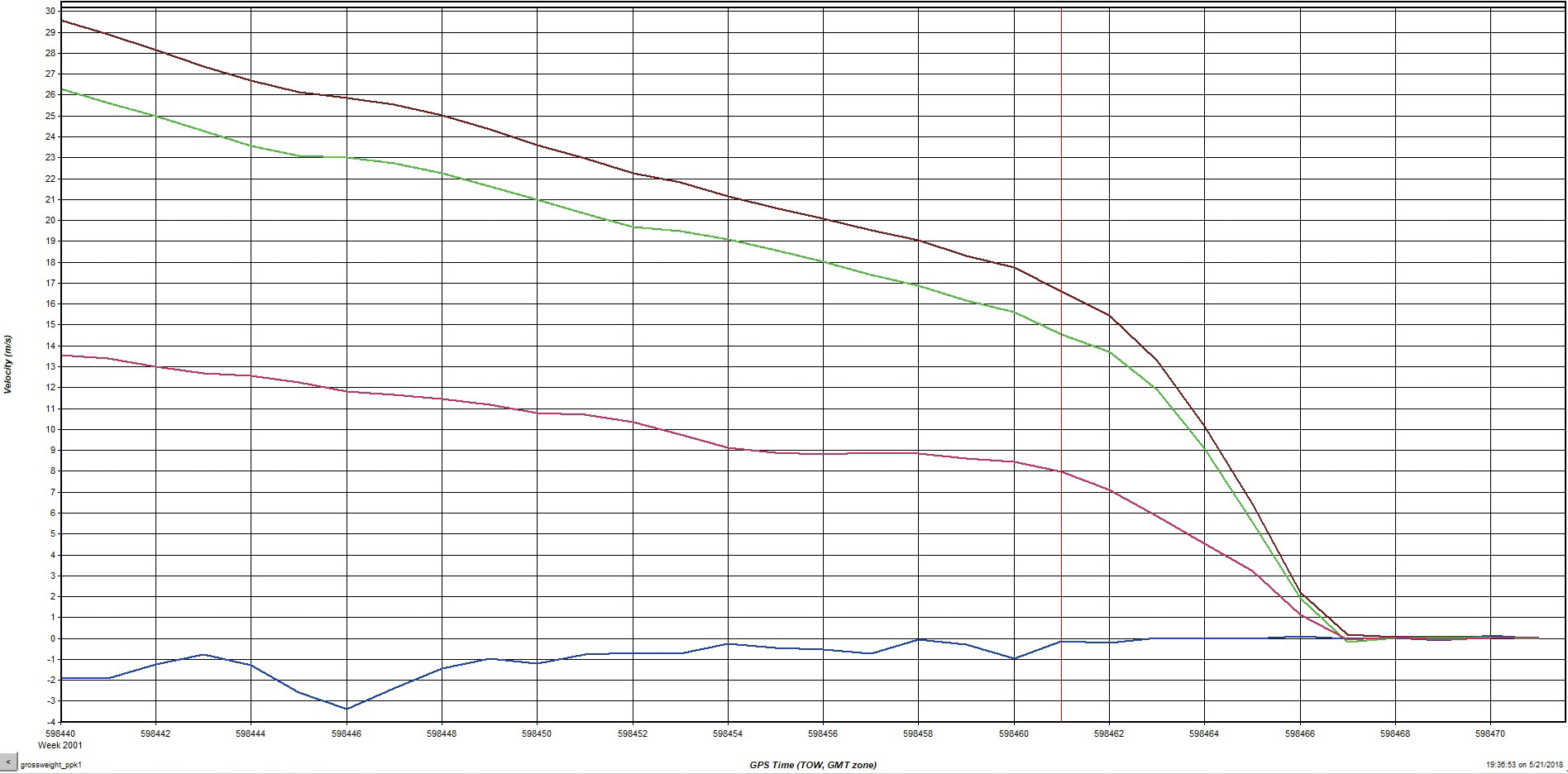

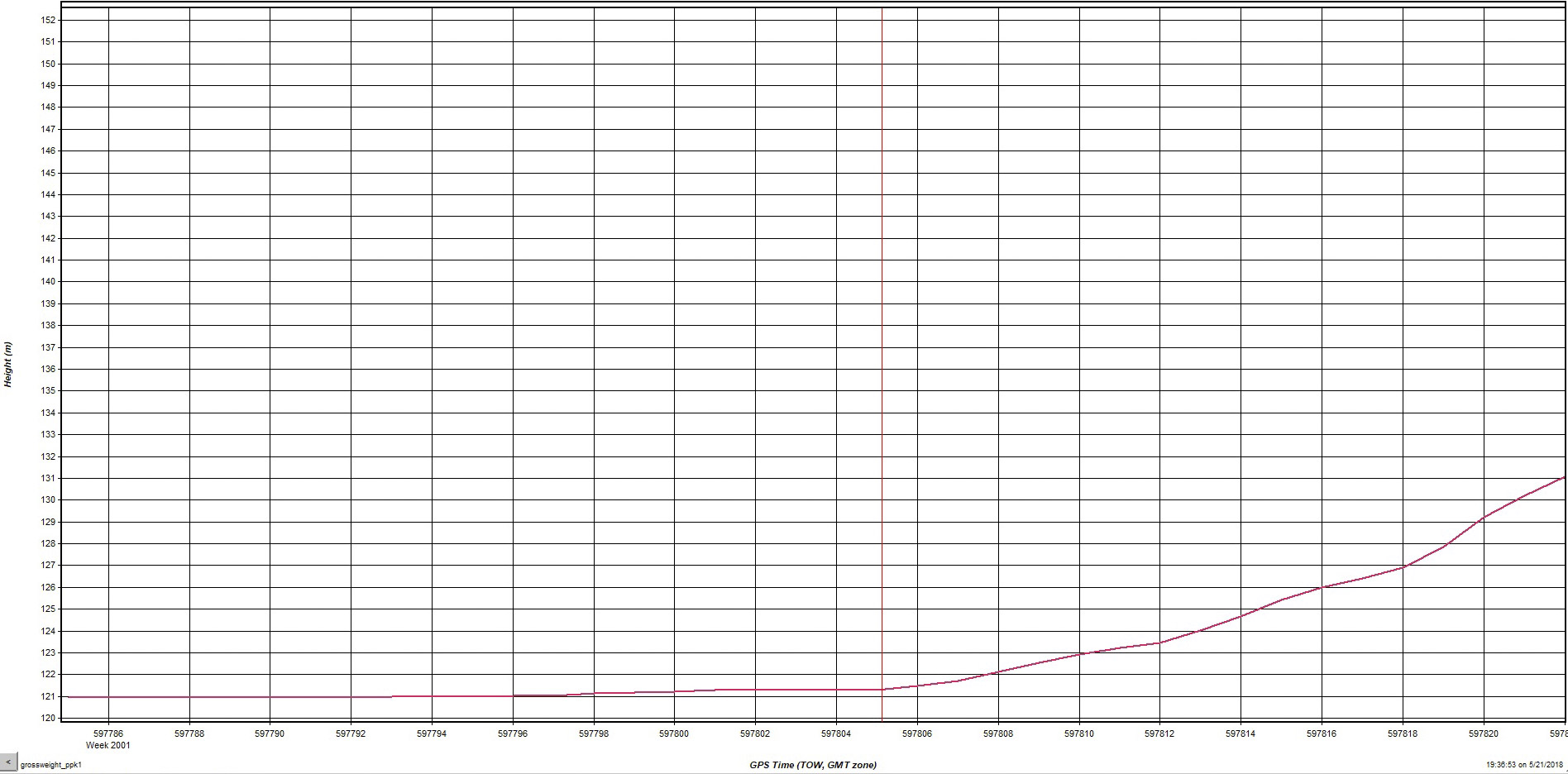

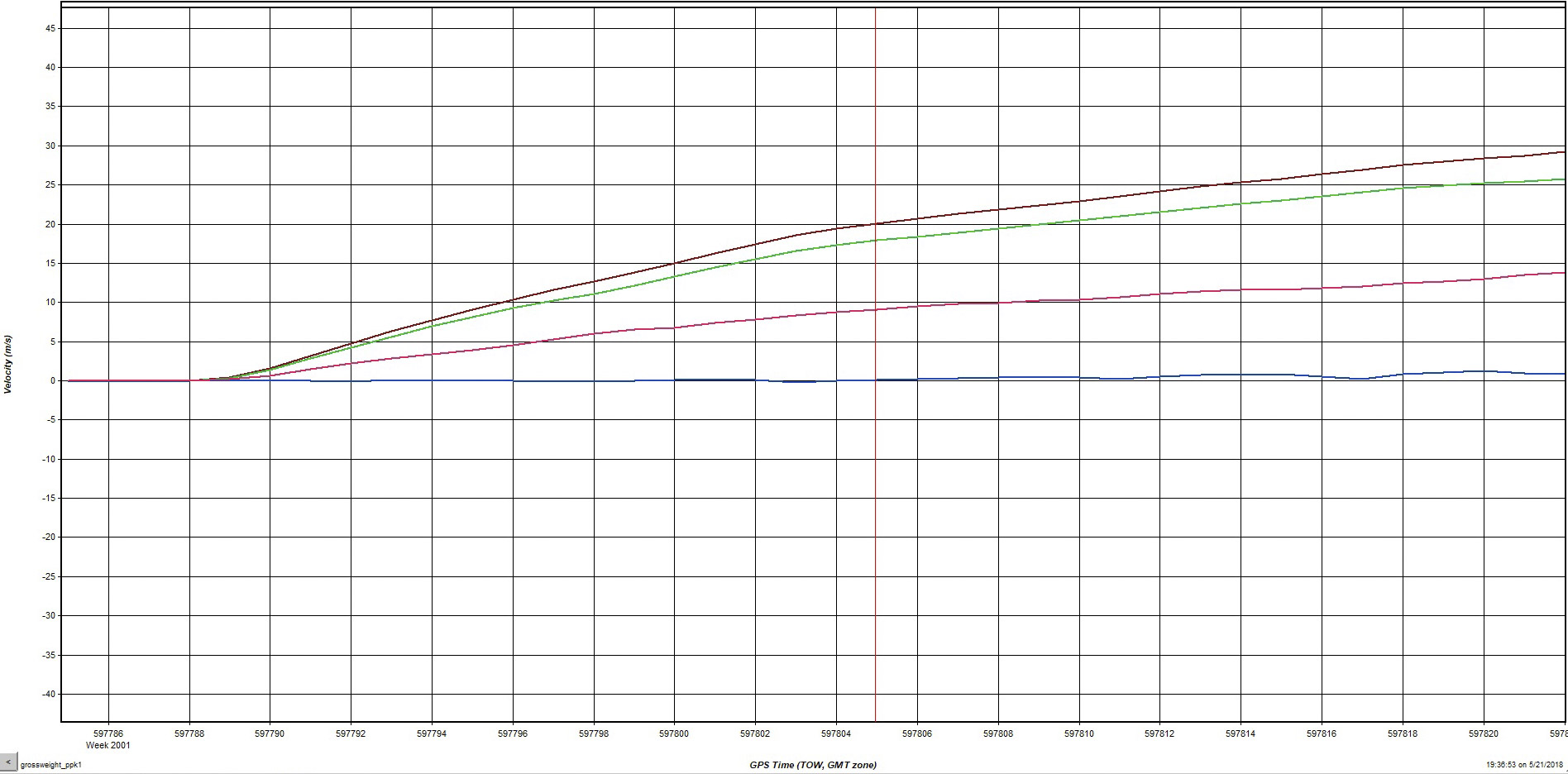

Here is some data from one of the GPS systems onboard my plane during the gross weight competition. At left is a height profile, where you can see I made two laps in the pattern. At right is my speed, broken up in into X (red), Y (green), Z (blue) and horizontal (brown) speed. For most everything I’m discussing here, the brown line (speed in the direction of flight) is the most important parameter. In these plots, the vertical grid lines are 50 seconds apart, but in the ones below I zoom in to show second-by-second details. The purpose of overlaying these two plots like this is so that you can match features at the same time, such that you can determine how fast the plane was in a certain phase of flight. In the speed plot, from left to right, you can see me first taxiing to the runway (first smallish bump) then stopping (flat lines), then taxiing to the starting line on the runway (very small bump), then taking off and landing to a complete stop first really large bump), then taxiing again to the start of the runway and stopping, and then doing it all again. There’s nothing interesting about that, just help to navigate what we’re looking at.

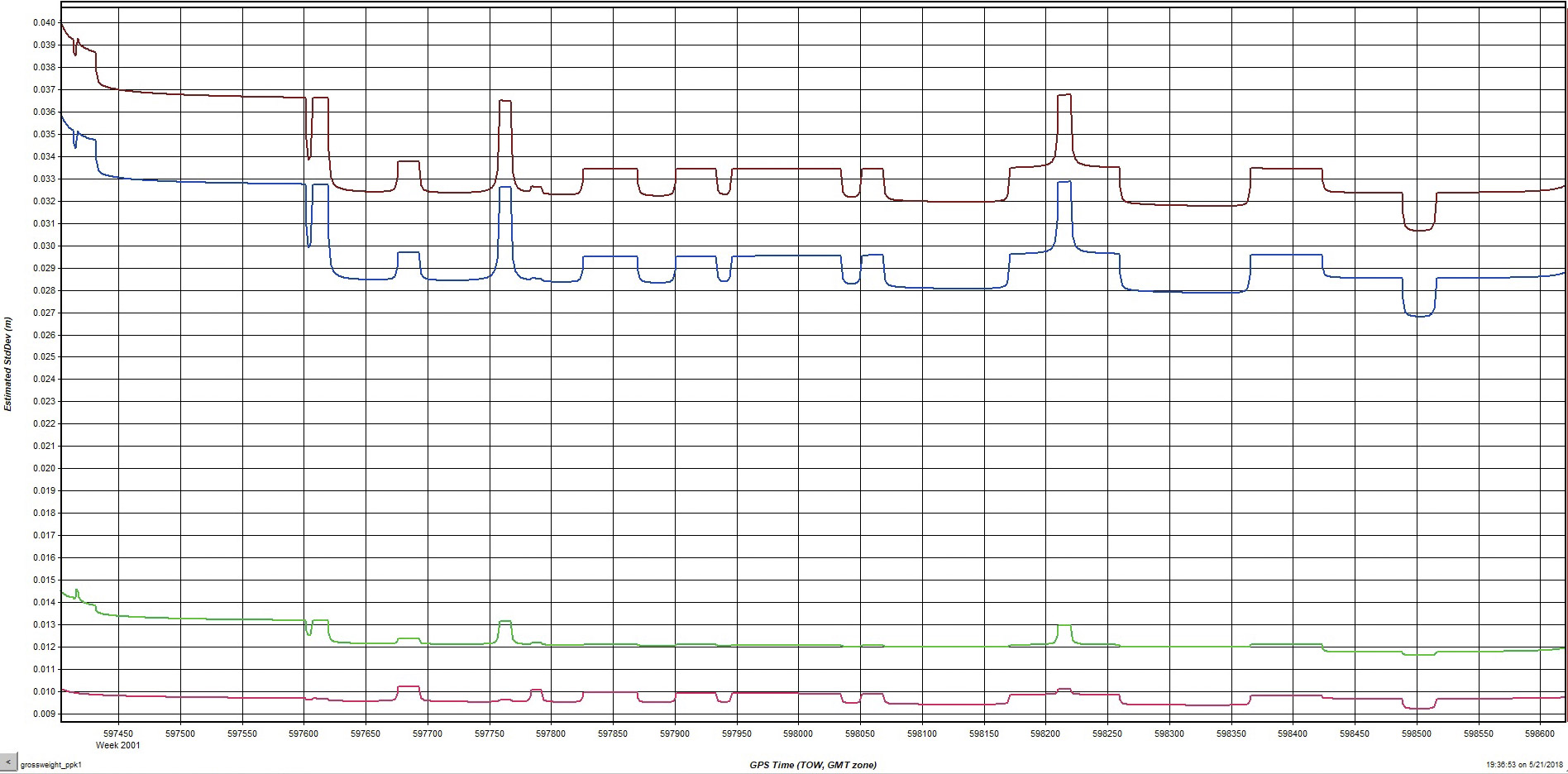

Here is a plot of accuracy, basically how well I know where I am in the sky. The red and green lines are X,Y accuracy, seen as about a 1 cm (less than half an inch). Vertical accuracy (blue) is about 3 cm. While I could do better with some care, this is pretty damn good as it is.

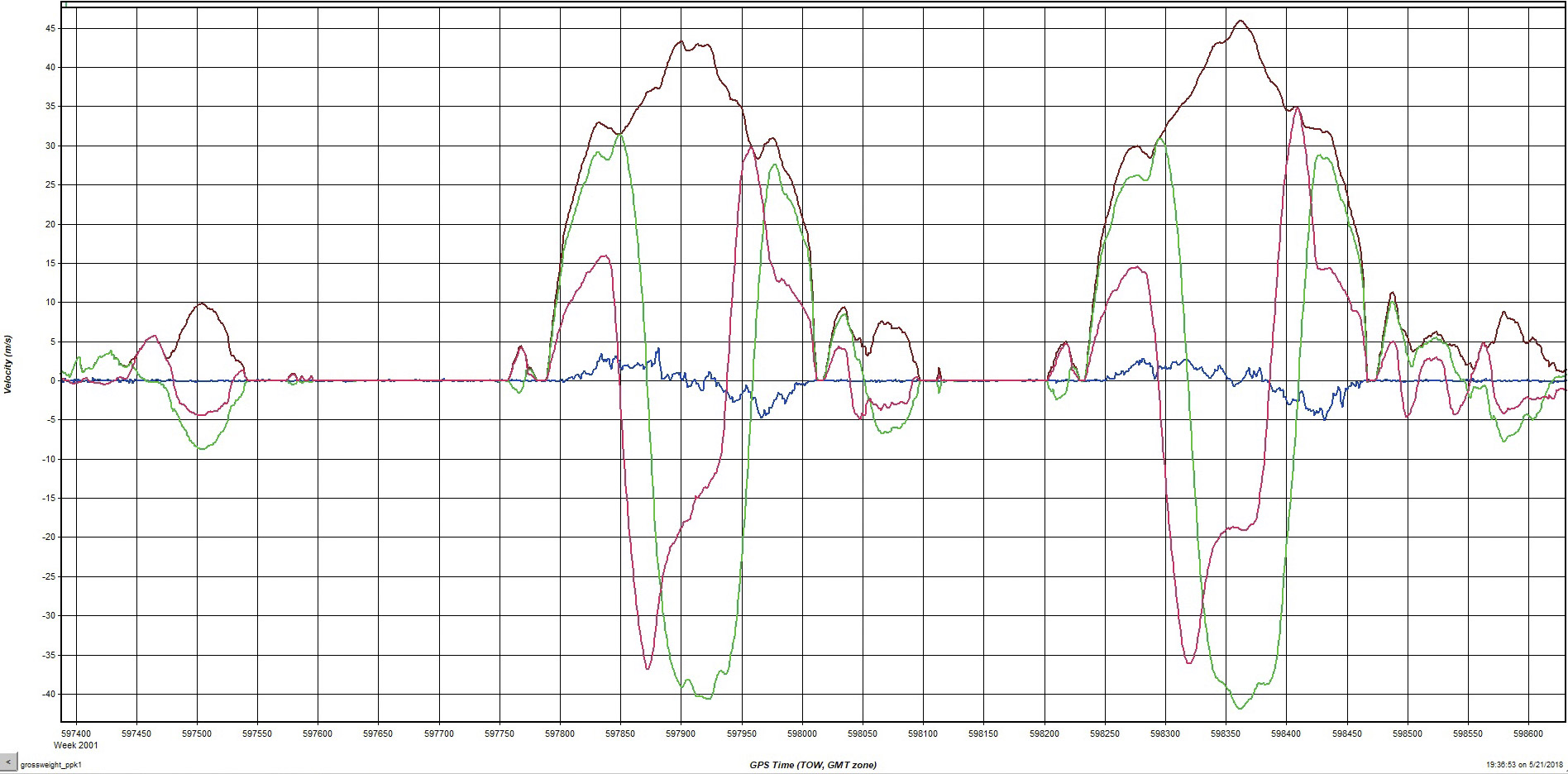

Here is my second landing, zoomed in; so this is at the end of the second large bump seen in the previous slider pair of images. The horizontal grid lines are 2 seconds apart. The vertical red line indicates where I touched down. You can see my speed (brown line) has an inflection point there, where I pulled power and wheel friction began slowing me down and about 2 seconds later I began braking (I didn’t want to smoke my bushwheels on the pavement…). At the time I landed, I was going about 17 meters per second (where the brown line intersects the vertical red line); that’s about 38 mph. I didn’t feel there was much left at that point but I had only flown this plane about 4 hours in the past two years, and 2 of those were on the way down here, so I didn’t want to get too frisky at gross weight, especially in front of a crowd… You can see in the videos below that my tail hit first and my main goal was to not DQ, as apparently I had landed about a foot short my first run. Looks like it hit just past the line, so I could have gained about 30 feet there and had I been on the gravel and braked harder I could have gained another 30 feet. Subtract that 60′ from my 220′, and you get basically what Shawn Holly and Mark Hasner got in their 170s. So ~150′ seems to be about the limit of one can expect from a 170 at gross weight, with the differences at that point purely in skill with a bit of luck. Though who knows what next year will bring! Here is one of my take-offs. Determining lift-off speed is a little trickier, but I think I’ve got it down to the second, as seen by the vertical red line. On the height graph at left, you can see my tail come up about 1-2′ for about 4 seconds after I begin moving (as seen in the speed plot at right) and stay up for about 6 seconds before I lift off. When my wheels left the ground, I was going about 20 meters per second (intersection of red vertical line with brown line), or about 45 mph. Stall speed from the book is about 52 mph. The combination of the Sportsman’s STOL cuff on the wings and ripping it off the ground a bit early explain the difference. You can see from the inflection points in the height graph that it was several seconds before I was able to leave ground effect and really begin climbing, and even that wasn’t very fast. That’s probably the most important difference between my plane’s performance and many of the others — when the others leave the ground, they can begin an aggressive climb rate quickly. For me, I’m lucky to get 100-200 feet per minute, so it’s not just runway length that matters, it’s what I need to clear at the end of that runway.

Here’s the cockpit view of the second of my second run in the gross weight competition; I cut out the downwind leg, but left the taxi back to the ramp to give a sense of the what the scene was like. This is a 360 video, but it only seems to work on a computer, not phones. I like the 360 aspect here because I can focus on my watching my technique, or focus on the runway markings, or focus on the crowd. My technique, for better or worse, was to start with one notch of flaps so that I could easily grab the handle, get the tail up as soon as I could to reduce tire drag and slice the wind better, then once I accelerated enough and felt the tail get lighter, pull in as much flap as it took to break ground without bouncing the tail, and then white knuckle it until it actually started flying. In watching others, I could see many tried to pull it off too soon and started dragging the tail again; I probably waited too long, but I knew I wasn’t actually in danger of winning anything so I was trying to find my comfort limits for the real world. The look of relief on my face once it actually started flying was priceless. And yes, I did turn the wrong way on the taxiway after landing…

Here’s an exterior view of that same landing.

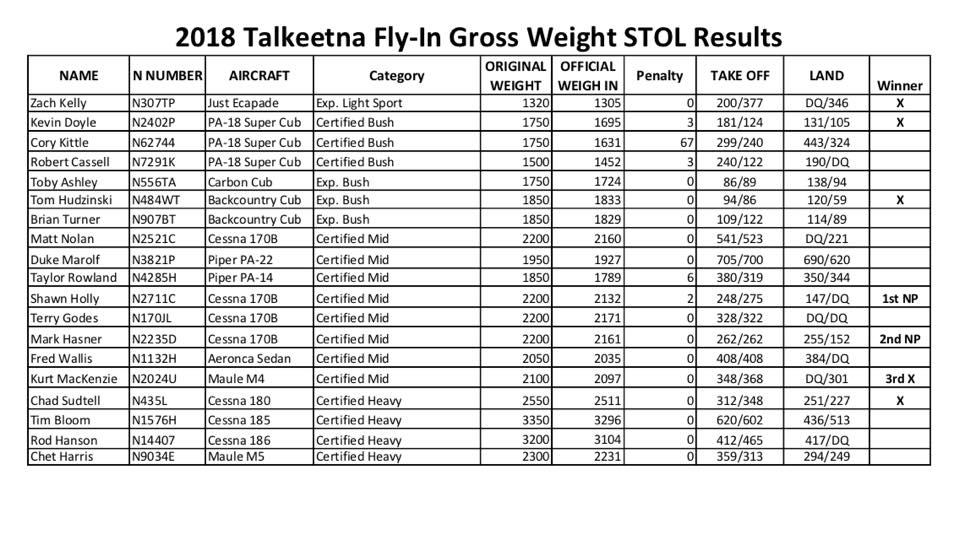

Here are the results of the first Gross Weight STOL Competition in Alaska. I think another neat way to present or rank these data would be in a Beat the Book format. That is, compare your actual STOL performance to what your airplane’s pilot handbook says your performance should be. The book value for take-off and landing rolls for my 170B are 650′ and 460′ and mine here were 523′ and 221′. So I beat my book’s numbers by 122′ and 239′ (or 80% and 48%) respectively. I guess with a little digging we could do that for the rest of the planes (though not sure about the experimentals). In future years, another variant of the presentation could be Beat Your Best, that is to compare the improvement of your own performance.

The next event after the STOL competition was the Aerial Scavenger Hunt. I had never done this before so didn’t know what to expect. The general idea was minutes before the event, the competing flight crews were given a sheet with coordinates and feature names, then everyone races to their planes, takes off, and tries to find those features and take a photo of them to prove they were found. An extra point was also given for landing at each of the four air strips on the list rather than just photographing them. But the biggest score was worth 5 points — finding and retrieving a giant rubber duckie without deflating it. Clearly locals had an advantage in terms of finding the named features, and non-locals with a passenger had an advantage because the passenger could type in the coordinates to a GPS en route. Fortunately my passenger was eager to find the duck and took to entering coordinates into the GPS like water off a duck’s back.

My navigator was eager to find the rubber duckie!

This lake was one of the targets. Behind it are the huge glaciers flowing off the flanks of Denali, tallest mountain in North America.

Peter’s Gap was one of the targets too. On the radio it sounded like some people were going through it, but this was close enough for me, having never gone through it before. Turn’s out this is the high spot, so it likely would have been OK, but we were having enough fun as it was.

Weeping Angel thanked us for not going through.

Weeping Angel thanked us for not going through.

After the Scavenger Hunt was over, we enjoyed some adult beverages at the Denali Brewery.

After the Scavenger Hunt was over, we enjoyed some adult beverages at the Denali Brewery.

As it turned out, nobody found the rubber duckie! Apparently an essential part of the hunt involved getting the organizers drunk enough to spill the beans as to where it was hidden, which we managed to do with some ease later that night…

As it turned out, nobody found the rubber duckie! Apparently an essential part of the hunt involved getting the organizers drunk enough to spill the beans as to where it was hidden, which we managed to do with some ease later that night…

With our successful fireside espionage the night before, our mission the next morning was to sneak out before any one noticed and use our new intel to rescue the waterfoul lost in the wilderness. For this mission we convinced Duke and Pamela join us in their Pacer. Apparently the reason it was lost in the first place is that the original list of targets included several air strips that were crossed off the list later that afternoon to save time, but the people crossing off the strips didnt know that the people who had put out the duckie the night before had done so at one of those strips! It was just as well, as it the strip in question was just over Peter’s Gap, which we were unable to get through yesterday. So with a vector in hand, we headed out.

This video shows our route into Duckie Gulch. In the first few shots you can see Duke and Pamela’s Pacer, then we go through the Peter’s Gap and around downhill into the gulch, with the final frames showing the ‘runway’. Despite it being late May, there was still a ton of snow out there and it was basically still winter just outside of town. In addition to testing a bunch of science gear, I also had two new video cameras I was trying out just for fun. My skill at using them and editing still leaves much to be desired, unlike my mapping skills…

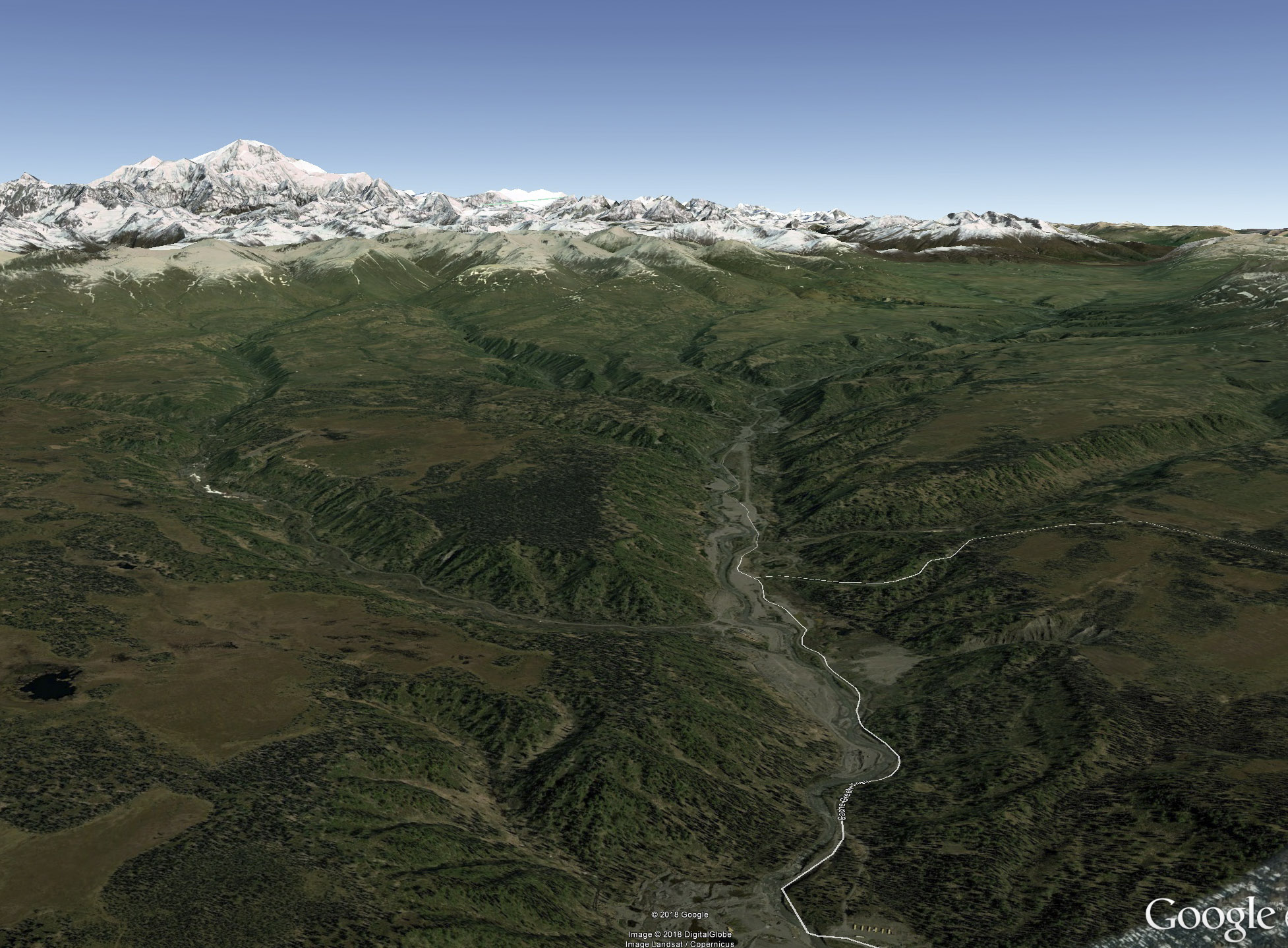

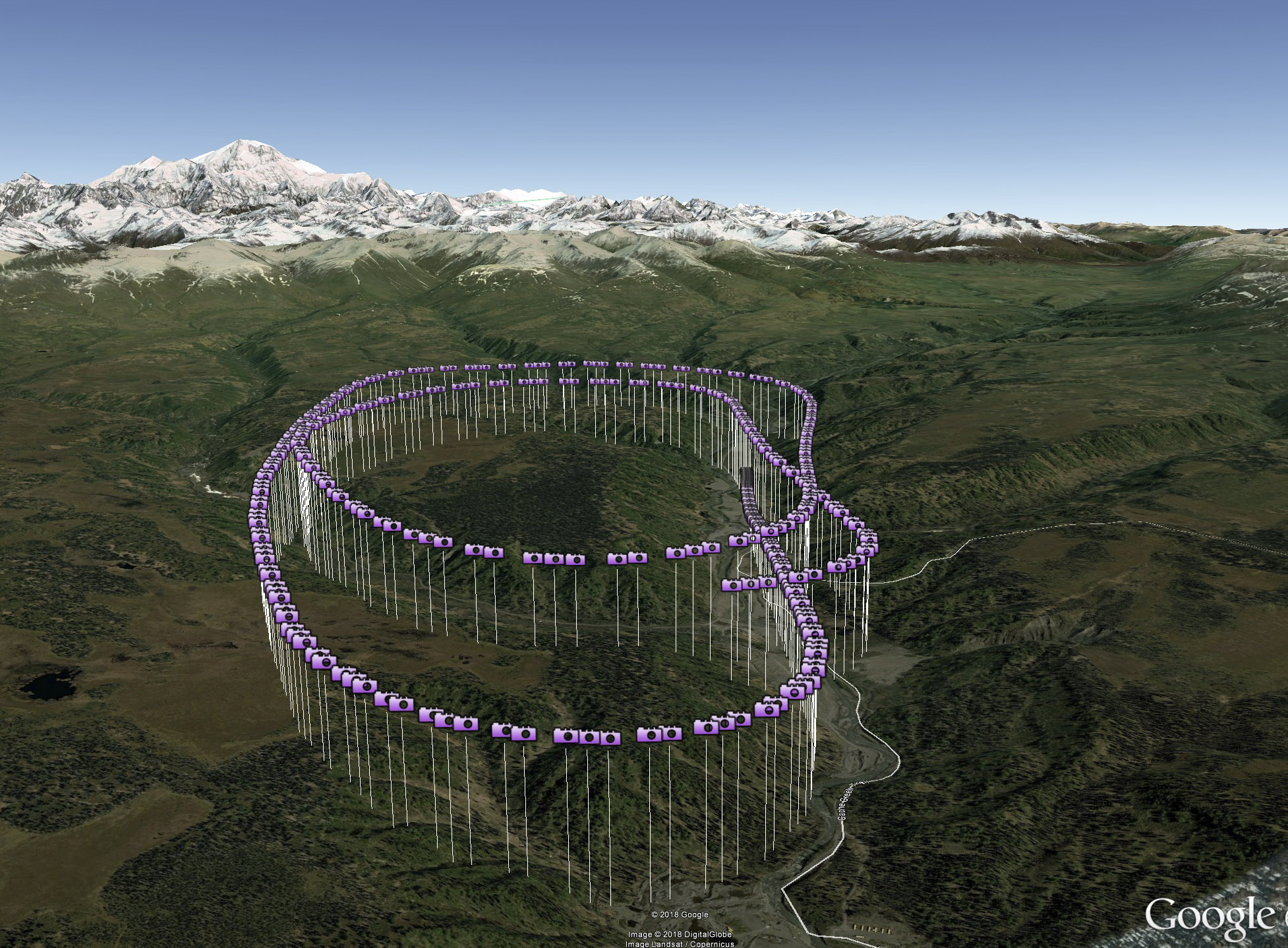

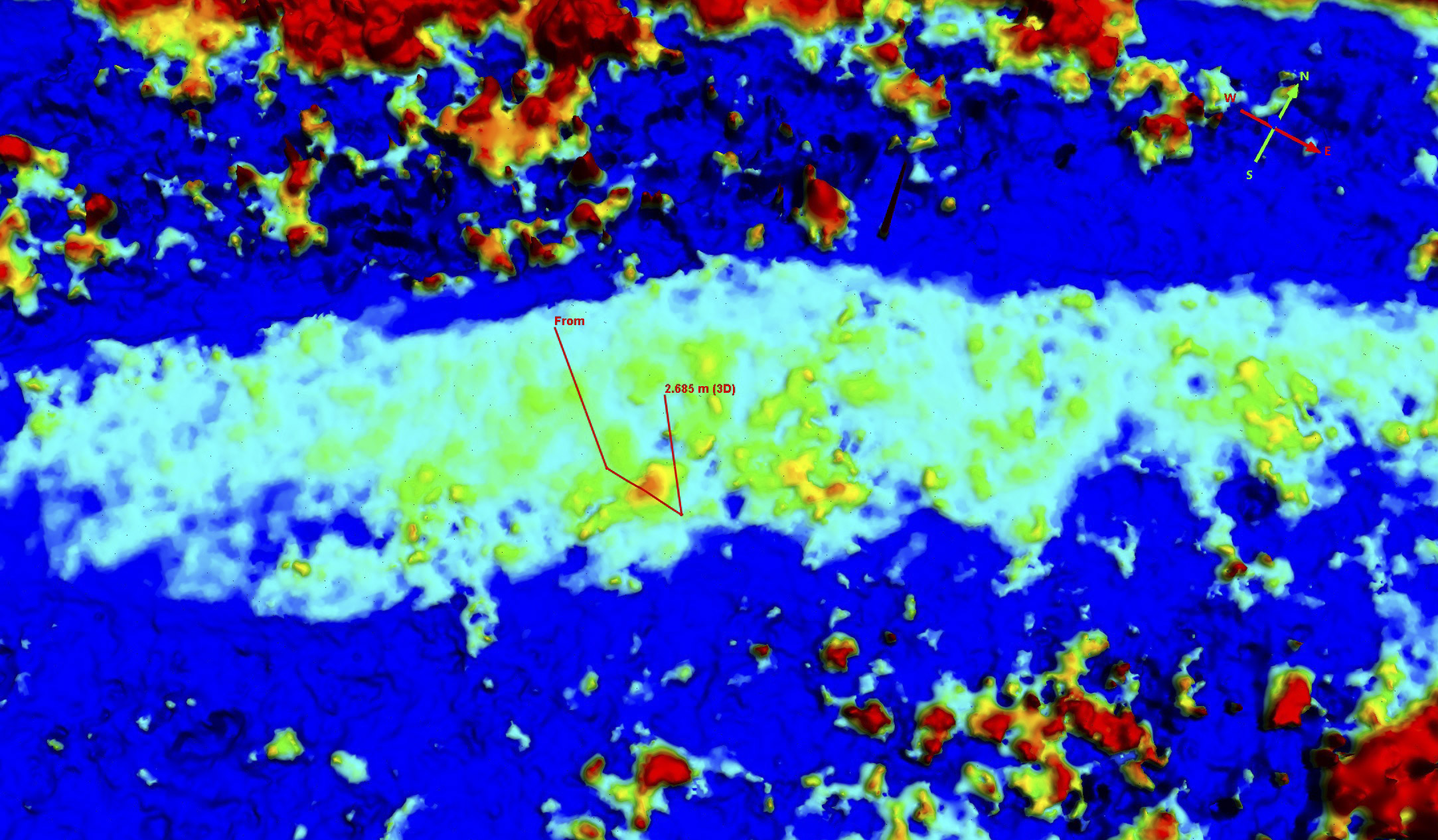

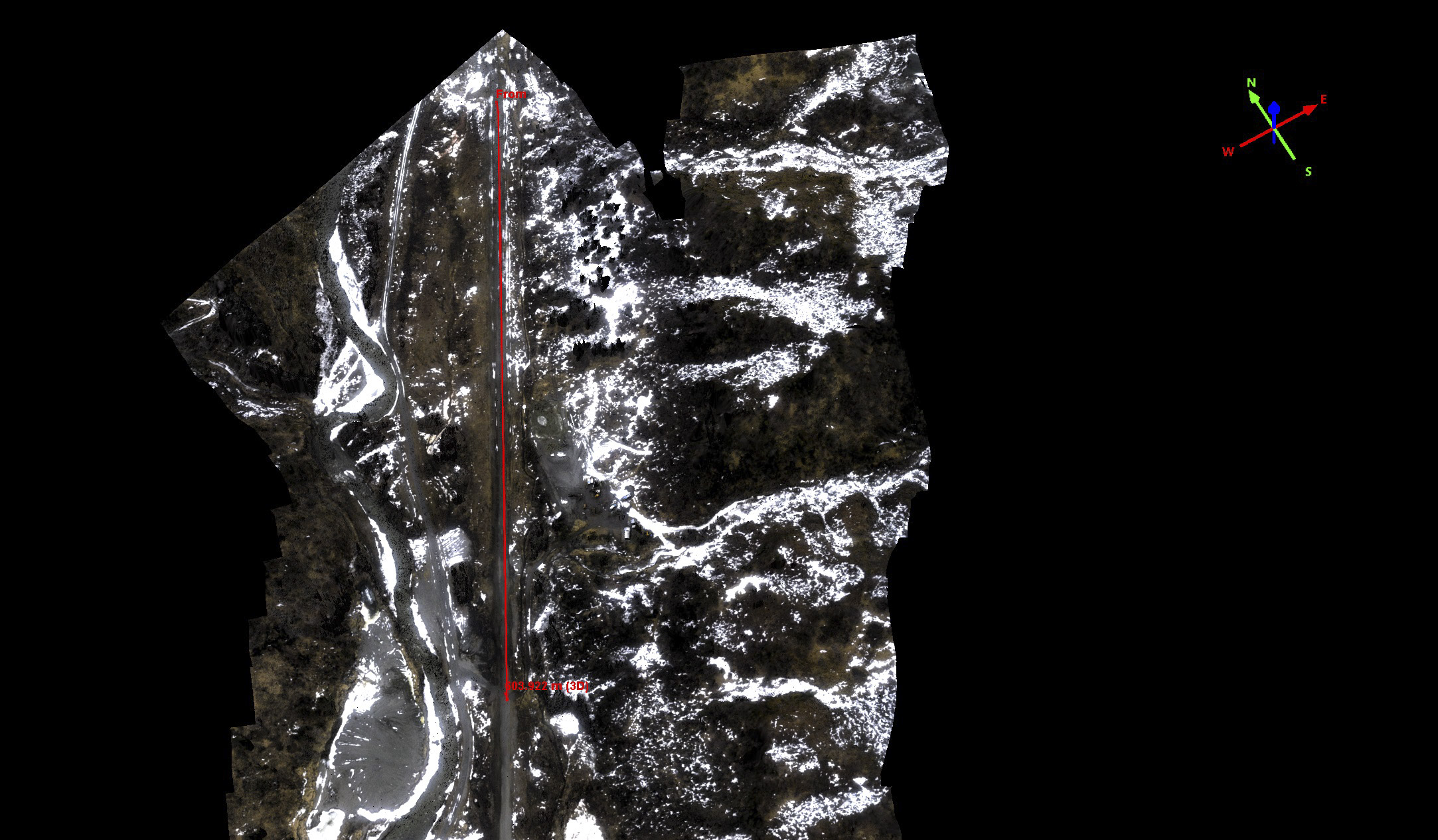

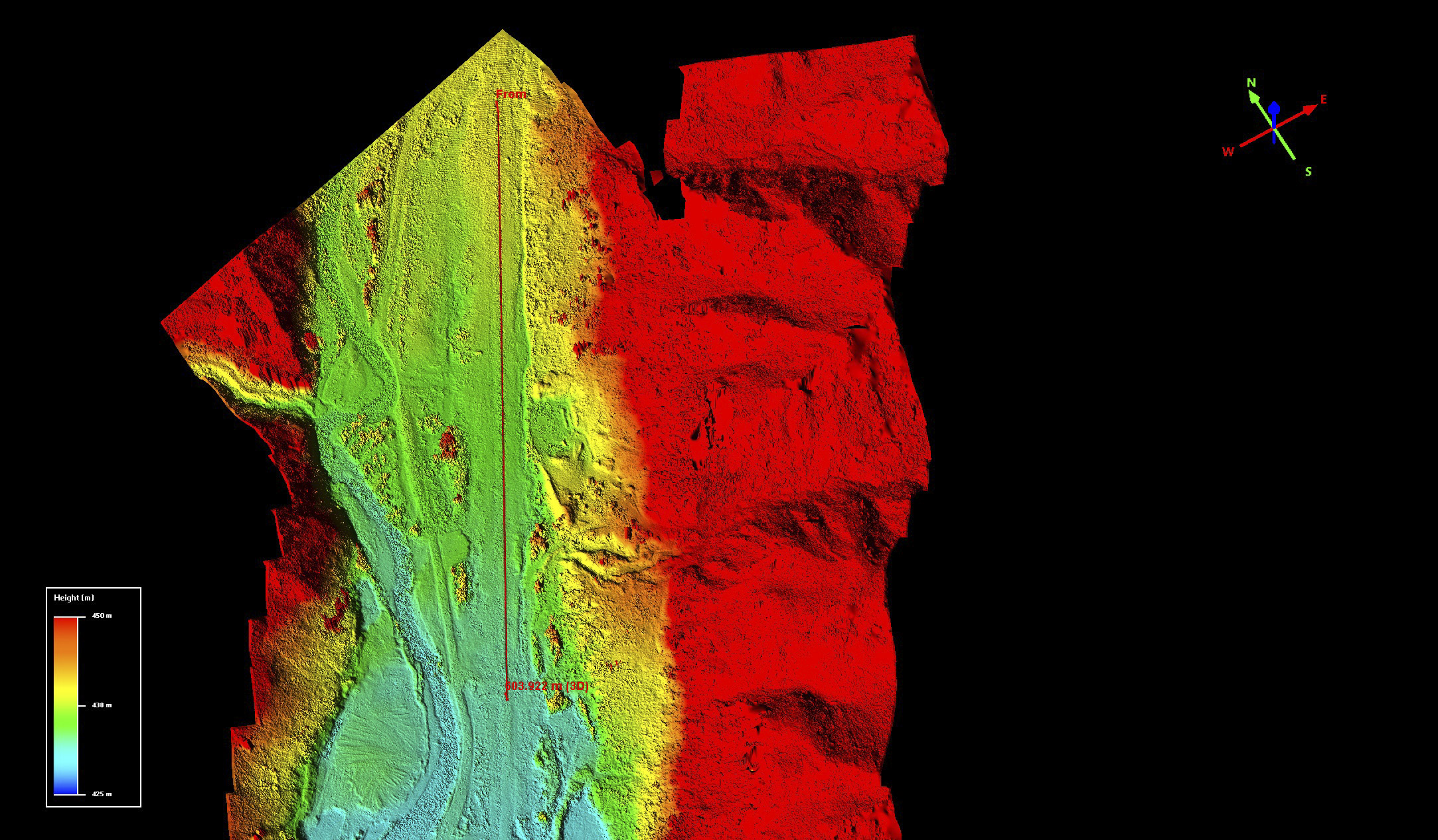

Of course having the world’s best mapping system installed in my plane I couldn’t help but to make a quick map while scoping out the landing spot. At right are the photos I took through the vertical camera port. With my system, I know the locations of where those photos where taken in the air to within about an inch. That extreme accuracy allows me to make maps accurate to not much more than that without needing any survey points on the ground. That’s what allowed us to make the most accurate map of Denali ever made last month; that’s Denali in the background and Peter’s Gap on the right.

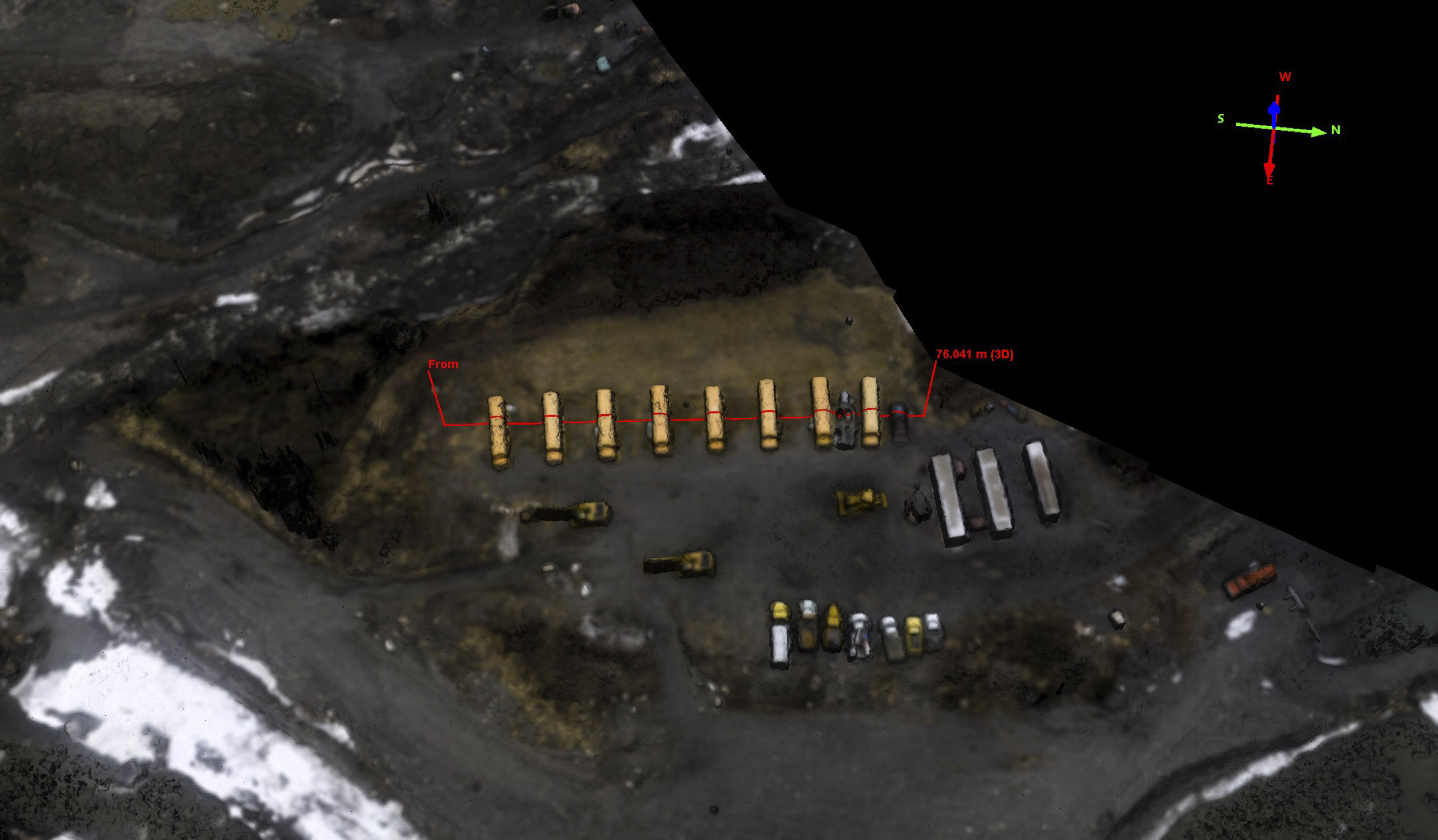

Here from one of my vertical photos you can see about where a road sort of turns into a runway, and just to the left on an island we found the giant rubber duckie.

Here from one of my vertical photos you can see about where a road sort of turns into a runway, and just to the left on an island we found the giant rubber duckie.

Here is a close-up of the island. No points for photos! Stage 2 was landing and rescue!

Here is a close-up of the island. No points for photos! Stage 2 was landing and rescue!

I was glad Duke and Pamela landed first. If I had to go around on short final, it would have been a white knuckle climb out to avoid the terrain, given the climb rate of a fully loaded 170B with O-300… They also scoped out and warned me about the especially rough terrain just past their plane, which I was quite thankful for as I taxied over it to park next to them. I like the two-circles view for some shots, but I don’t have a video editor that can handle them like this, so you get everything. It’s funny seeing yourself in high-attention situations; when Duke told me there were some potholes just past his plane, I really had no idea what to expect. If you look close, you’ll see me landing just over the top of their plane and how bouncy it is taxiing up to them afterwards.

Not sure really if this is a runway or a road, but I guess beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Now that we were on the ground, the fun really started… Thanks to Duke for braving the chilly waters and capturing some of the footage here.

Success! Now to get it home intact!

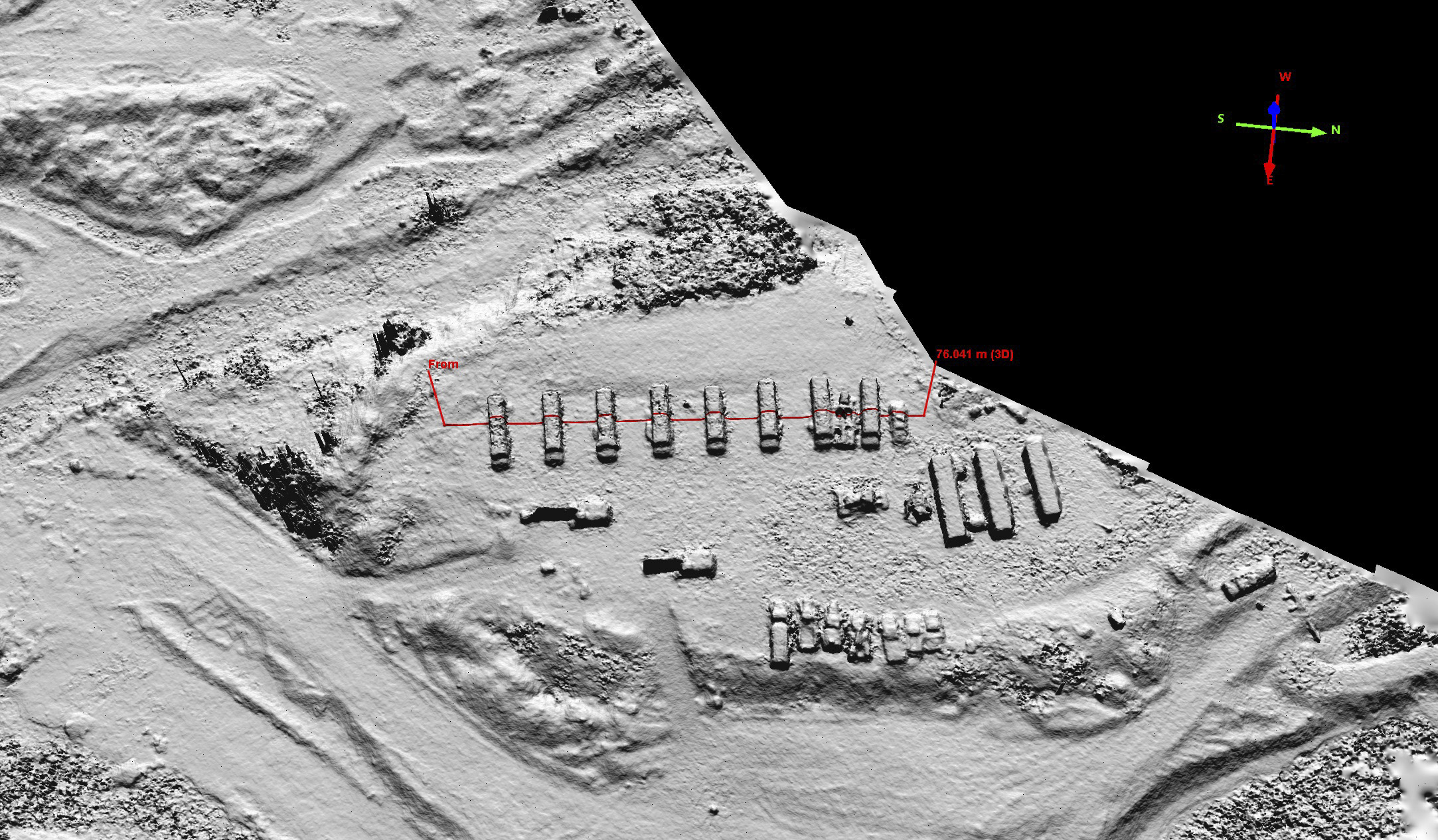

Here is school bus topography. Each bus is about 9 feet tall.

Here is school bus topography. Each bus is about 9 feet tall.

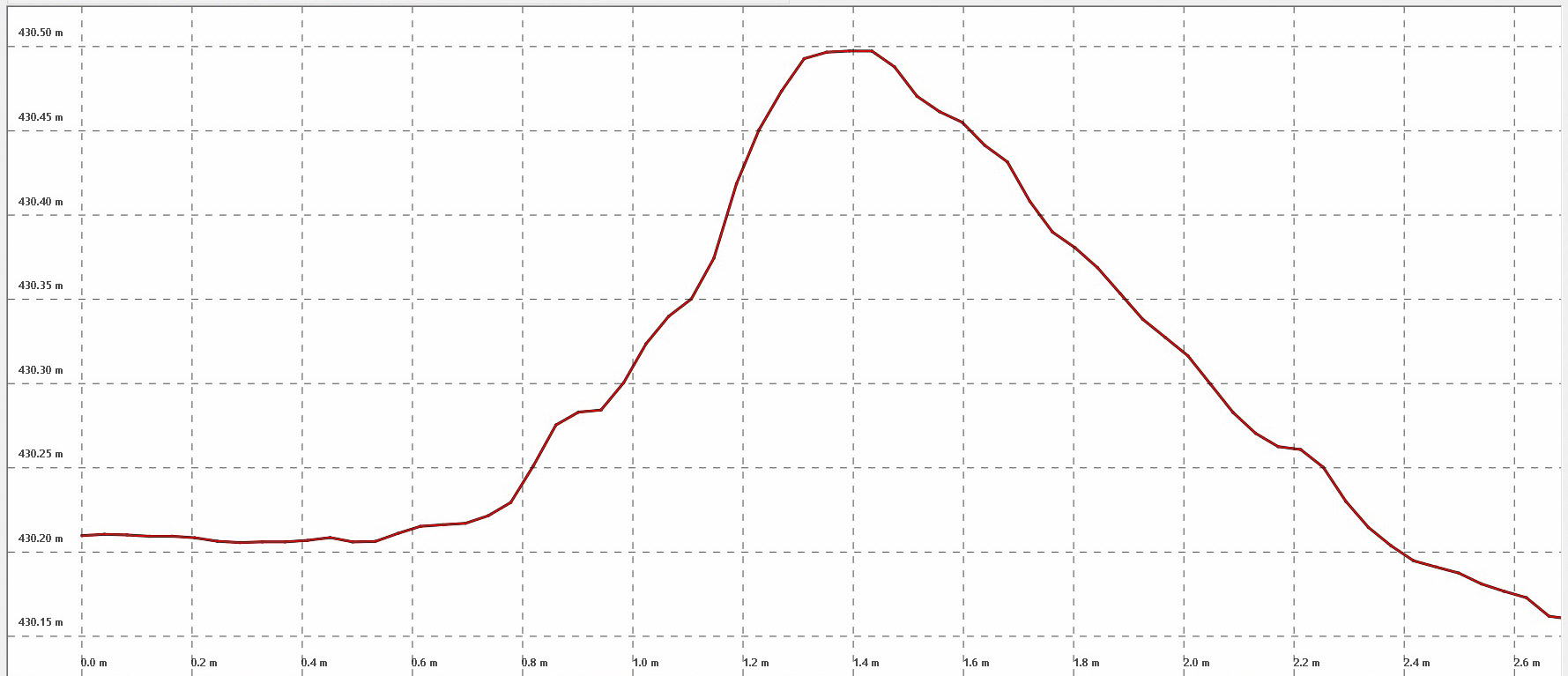

Here is rubber duckie topography. The horizontal grid lines here are 5 cm (about 2″) apart. The duckie’s butt was about 30 cm high, both as measured here and in the field. Not sure if we bank extra points for next year by measuring duckie topography this year, so just covering my bases. Reminds me of the work we did measuring the heights of actual giraffes and elephants in Botswana last fall.

Here is rubber duckie topography. The horizontal grid lines here are 5 cm (about 2″) apart. The duckie’s butt was about 30 cm high, both as measured here and in the field. Not sure if we bank extra points for next year by measuring duckie topography this year, so just covering my bases. Reminds me of the work we did measuring the heights of actual giraffes and elephants in Botswana last fall.

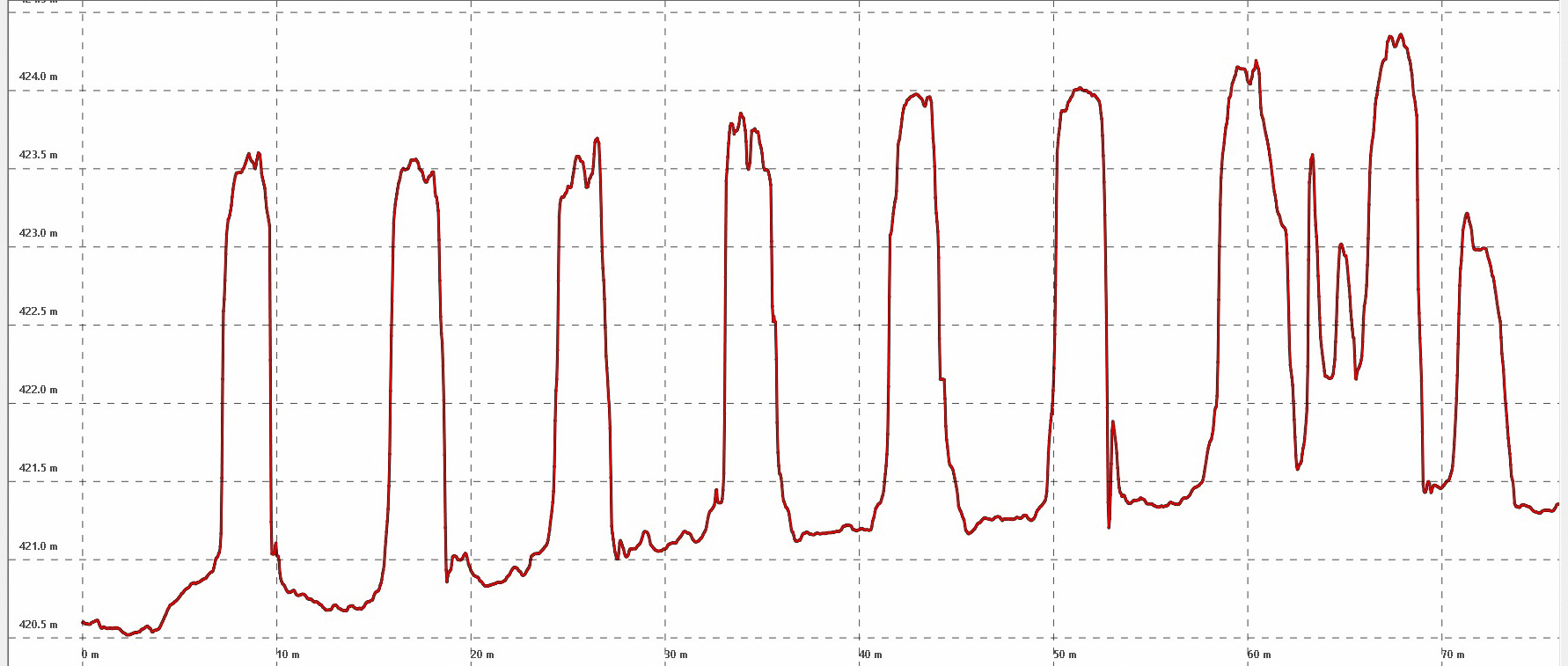

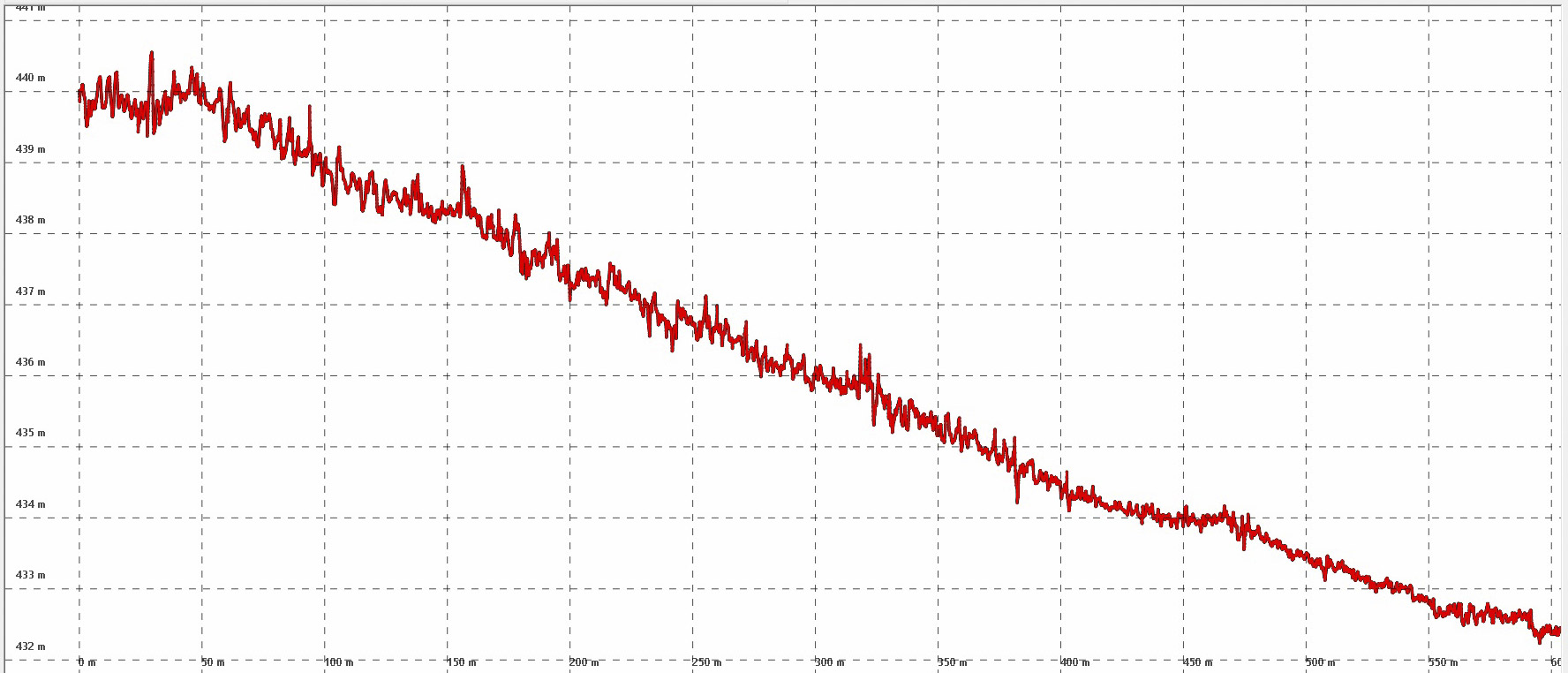

Here is an elevation transect of the runway, dropping about 30 feet in 1500 feet. I know from prior studies (and from taking off there) that the wiggles seen here are largely real. Each horizontal grid line is 1 meter apart, so those wiggles are in the 10-40 cm range, yuck!

Here is an elevation transect of the runway, dropping about 30 feet in 1500 feet. I know from prior studies (and from taking off there) that the wiggles seen here are largely real. Each horizontal grid line is 1 meter apart, so those wiggles are in the 10-40 cm range, yuck!

That’s one happy 12 year old! And one big duck in a small plane!

That’s one happy 12 year old! And one big duck in a small plane!

Here is a 360 video of our take off from Duckie Gulch. It seems the 360 part only works from a computer, not a phone.

Here is the extended version of our departure with our new passenger, who apparently had trouble digesting that morning’s non-vegan pancakes at the airport… I think the full version and the side-by-side video give a good sense of what dealing with a place like this is like, including the perils of making a u-turn on such a tight, bumpy strip. Note also that I wasn’t flying below terrain so long for the better view, that was me trying to climb; taking off uphill likely would have been disastrous. But the real reason you get it all is because I cant figure out how to edit it…

Here is some of the trip back to Talkeetna. You can see Duke and Pamela come into view on the left, then the landing in Talkeetna, and taxiing through the event. It’s spherical on a computer, so you can drag the view around with your mouse.

Turner is ready to claim his prize!

Turner is ready to claim his prize!

Victory!

The last event of the Fly In was an aircraft judging competition, like who’s plane is prettiest. At this point we were packing up and ready to get home to get some sleep. The judges idly walked by while I was loading the plane, and I joked about this plane having inner beauty as my flying office, with 8 different GPS installed and connected by a tanglefuck of wiring in addition to the 5 different wifi signals I use to share the data between devices. I’m not sure if was that or the mud I managed to get on top of the wings rescuing the duckie, but at the awards ceremony I was surprised to learn that 2521C won the Most Alaskan Airplane award!

This was the second biggest surprise for me at the Fly In.

This was the second biggest surprise for me at the Fly In.

I think this may have had something to do with it.

I think this may have had something to do with it.

Or this, the cluster of wiring I’m removing here that was splayed out all over the floor.

The flight home was uneventful, but another opportunity to acquire data testing different GPS and camera to keep my fodar one step ahead of the competition.

That day I learned a new article had come out in the papers about our Denali mapping work, and this led to a TV interview the next morning. Then it’s been two days studying the new data, learning how to do some basic editing of my new fun cameras, and putting this blog together. Overall it was a great mixture of fun and work and we’re both looking forward to the next Talkeetna Fly In, and maybe even hosting one in Fairbanks in early October this year!

This was the biggest surprise for me at the Fly In — neither of us was expecting to do anything remotely like this when we flew to Talkeetna last Friday, but I don’t think either of us will ever forget it!