I Saw Sea Ice Off the Sea Shore

Ever since we demonstrated how well fodar can map snow depths in this 2015 paper, our field seasons have been starting earlier and earlier, with 2020 being no exception. This past weekend we took on perhaps our most challenging photogrammetric project yet – mapping sea ice 150 miles northeast of Deadhorse during the ICEX 2020 project.

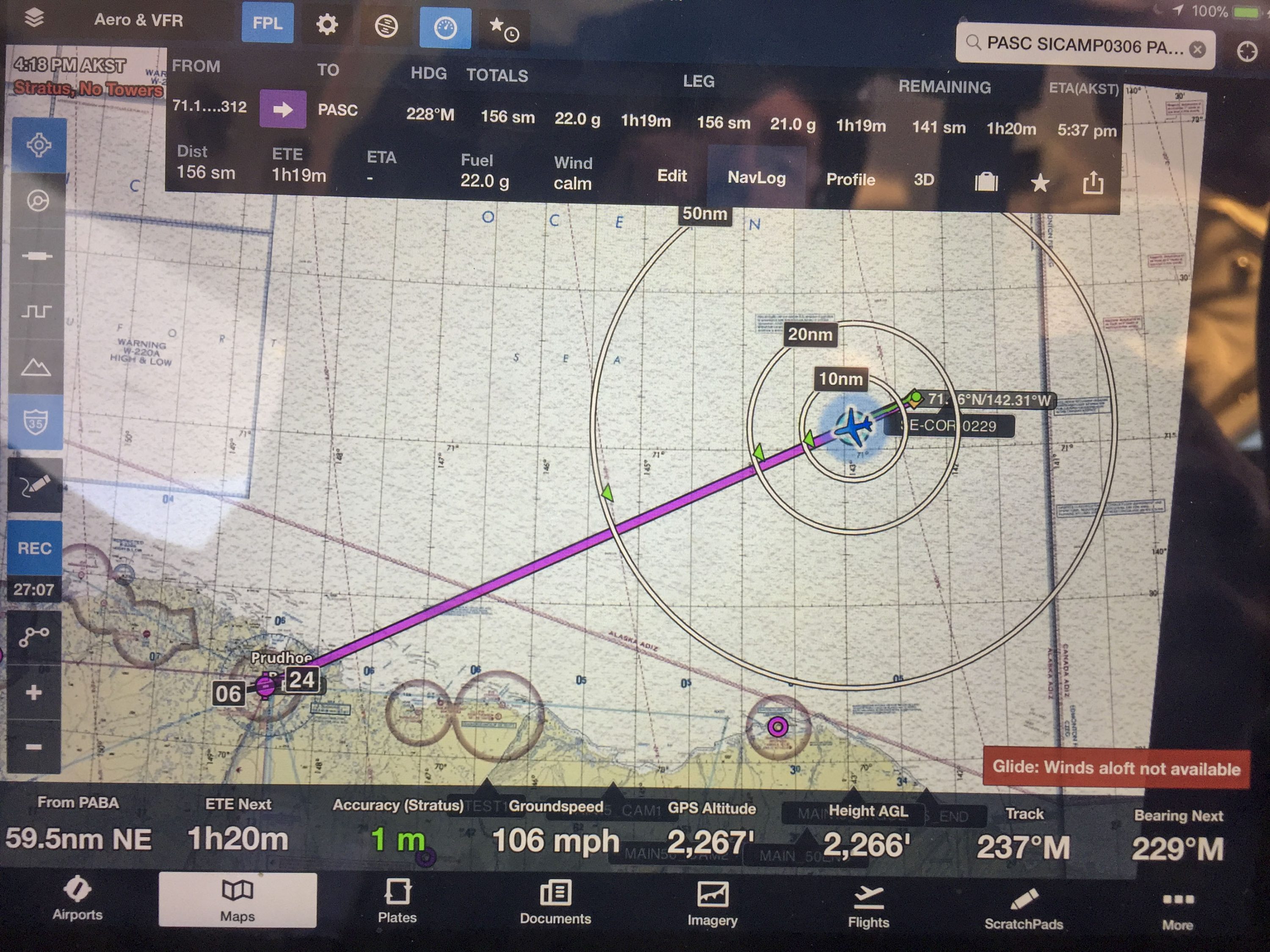

The first inklings of this project actually happening came about a month ago, followed a few weeks later by a contract to do some cool science while I was vacationing in California. So I came home early and after a frantic week of digging out the plane, fixing it up (thanks Aircom!), prepping the fodar and arctic winter survival gear I headed north to Deadhorse to catch a good weather window, arriving at sunset on Thursday March 6 and getting hangered in the fantastic DAC-West facility. The next morning, after a slow start to find work-arounds to deal with two iPads that died over night and a GPS issue that Novatel’s excellent tech support was helpful with, I was heading out over the frozen ocean on a beautiful CAVU day.

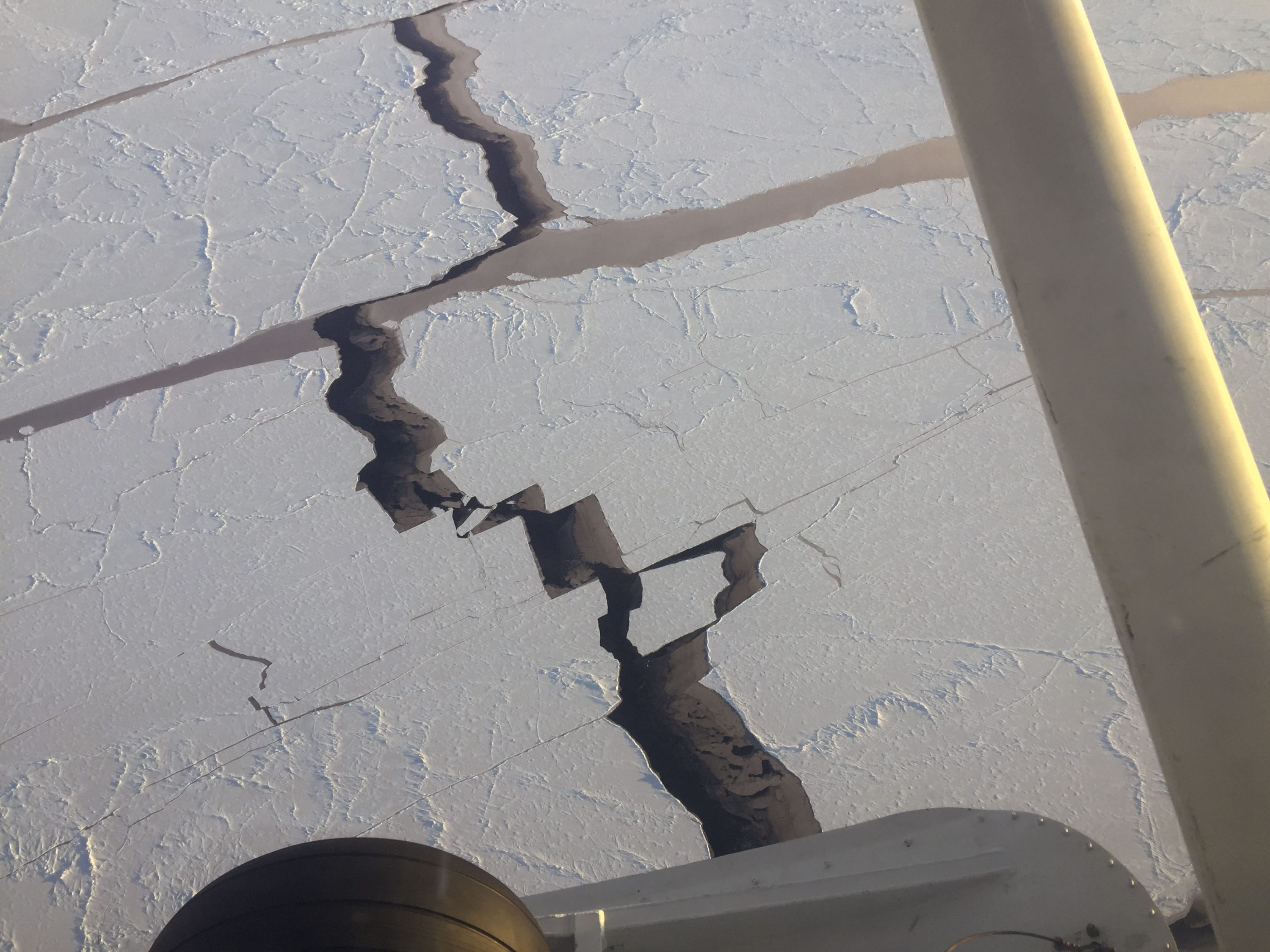

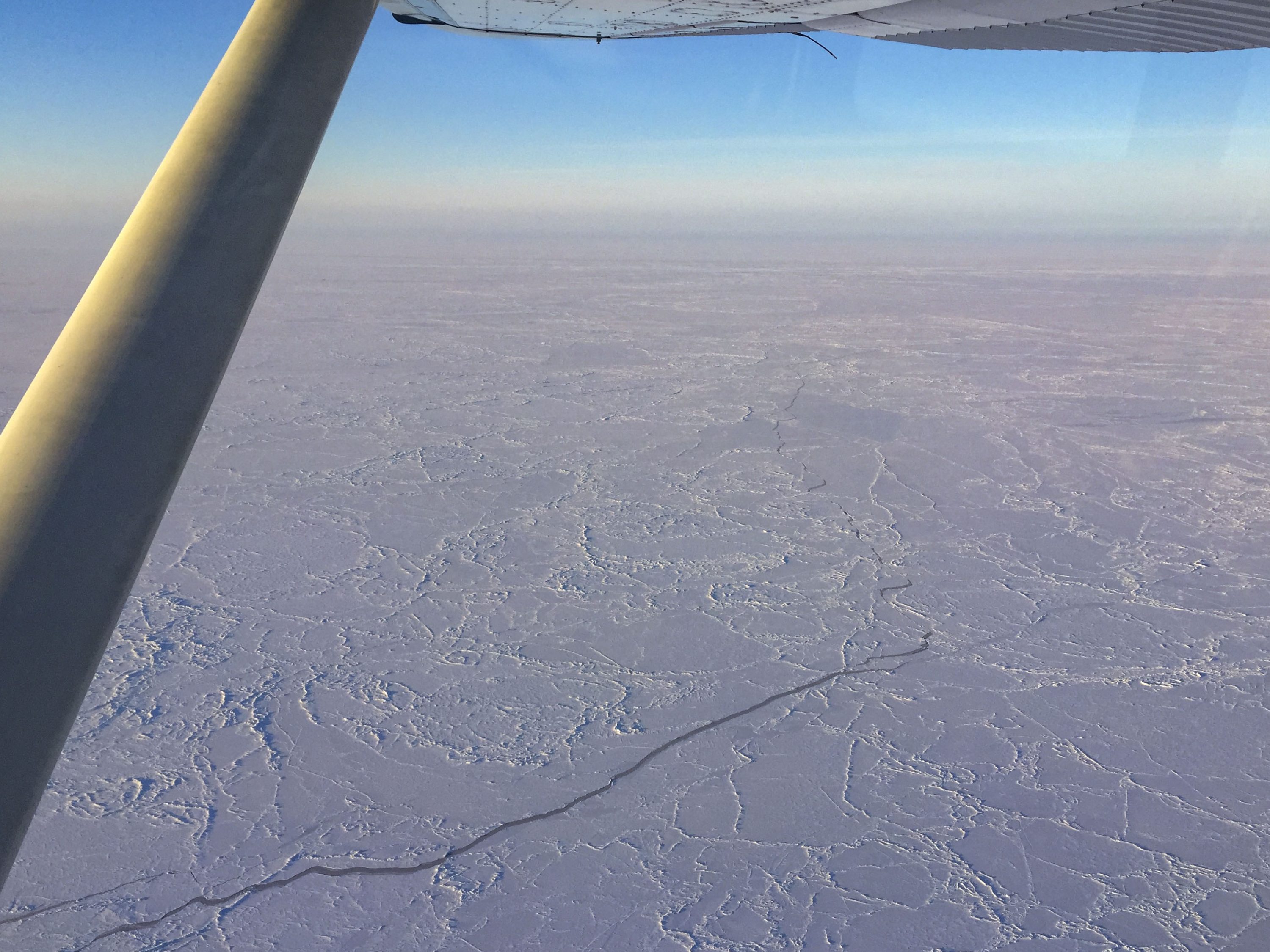

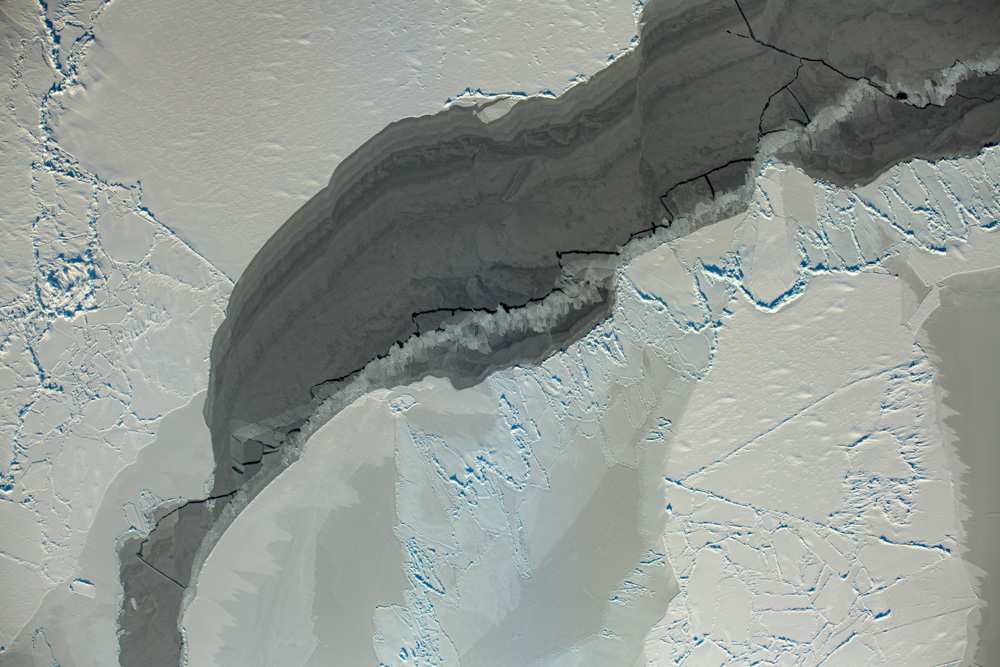

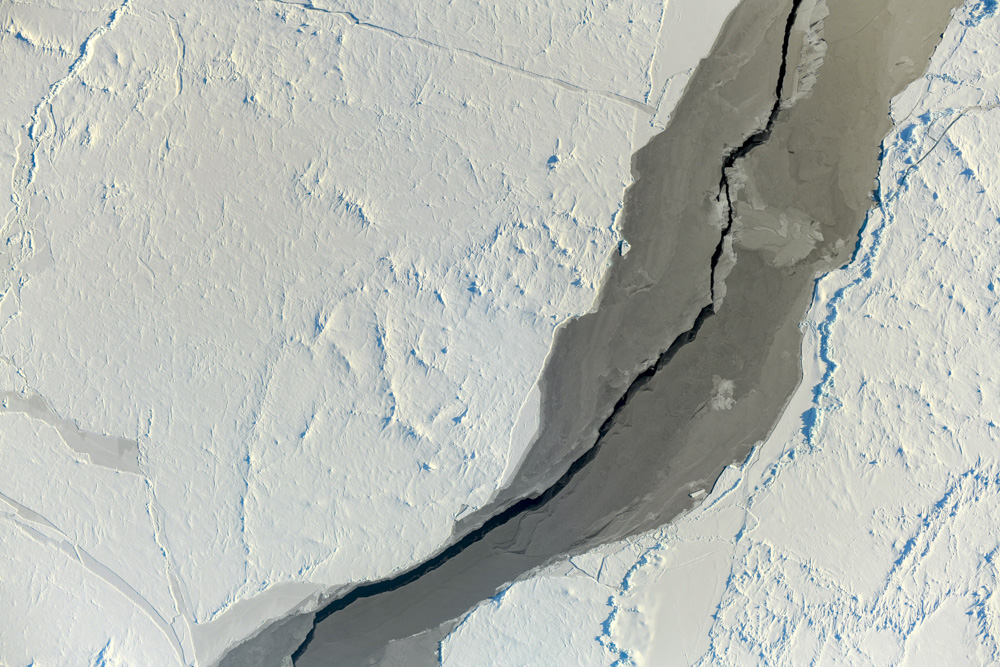

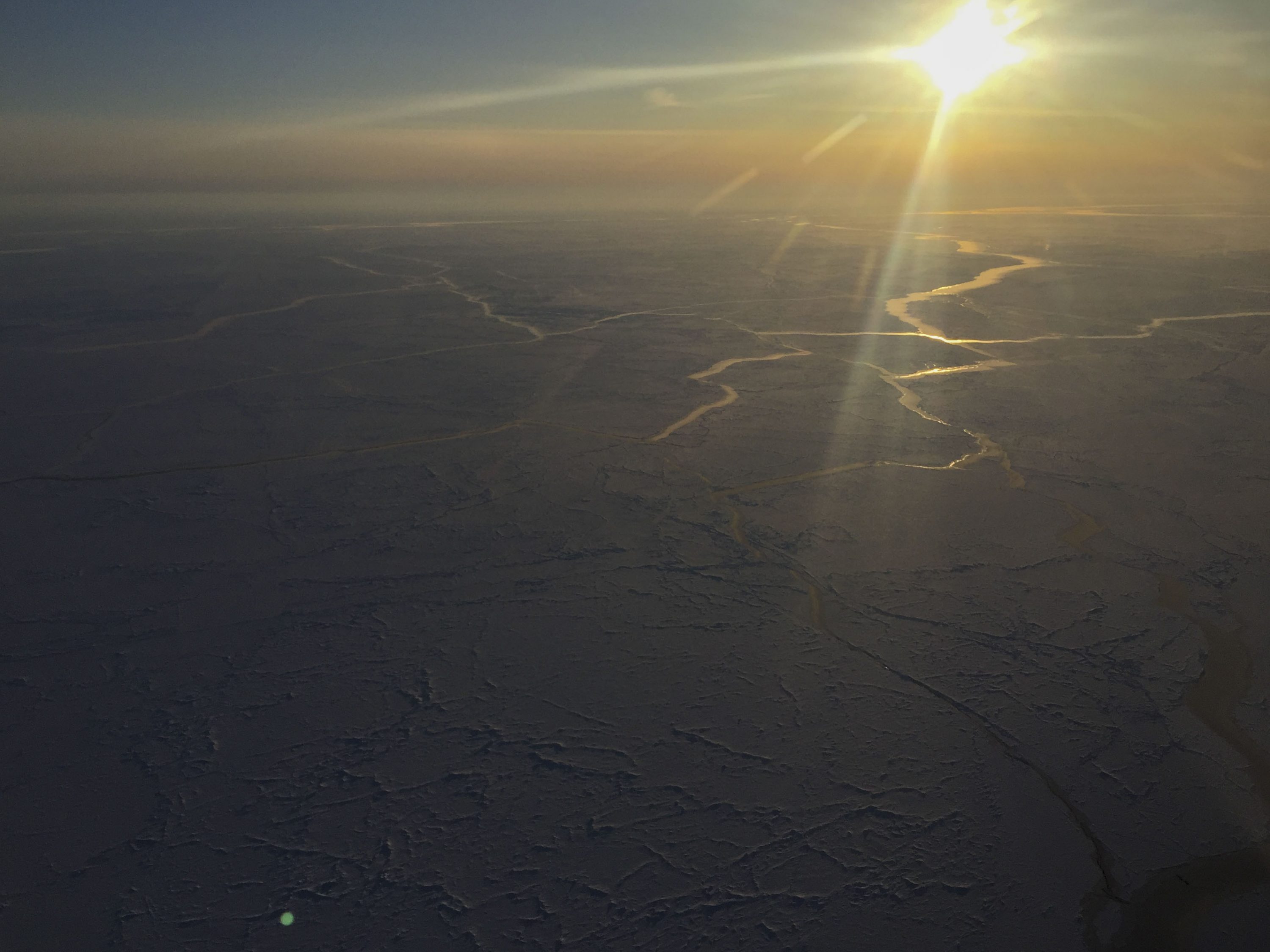

I had never flown over sea ice before, except when cutting some corners while flying along the coast and doing some test projects in sight of land, so it was a new experience for me. Logistically the challenge is of course that one is truly at the edge of nowhere – I’ve spent a lot of time in some very remote places, but this probably tops the list. In terms of flying, the sea ice is in general much smoother than ice bergs frozen into place (sea ice is frozen ocean water, unlike icebergs which are chunks of glacier ice that have calved into the ocean, so as such sea ice is more like lake ice), offering lots of possibilities for emergency landings, especially on skis. Still, it’s not a particularly forgiving place to be stuck. And because the wind pushes the ice around, it crumples into each other creating ridges or splits apart creating open water leads, thus flat light is also an issue as such an overcast makes it impossible to see the surface roughness on landing, and even in the air it can easily get disorienting to not have a horizon to follow. So for single-engine VFR hippies like me, good weather is essential. The good news logistically is that the ICEX base has it’s own helicopter, there are several military submarines lurking beneath it, and there are at 3 larger aircraft zipping back and forth each day ferrying supplies or people — so as things go on sea ice I couldn’t ask for a better safety net!

Photogrammetrically there are several challenges with this project. Snow can be difficult to photograph in such a way to provide sufficient photogrammetric contrast; all that’s really needed is some good sunshine, but sunshine isn’t something one can schedule. I wasn’t planning to start this trip until Sunday, but given that Friday was forecast to be a perfect day for both flying and photogrammetry, I pushed hard to get here by Thursday. The major new challenge to deal with is that sea ice is moving all the time. The technique I developed to make such awesome maps without using any ground control relies on my ability to determine the position of the camera to within a few centimeters at the time the photos were taken. Well, if the ground is actually moving, all that goes out the window, it’s like I no longer know where my photos were taken. In this case, the sea ice is moving about 5-10 cm/s – so despite knowing where my photos are in 3D space to within 5 cm, by the time I take the next photo the landscape has moved that much so my error is at least that high. During a two hour mission, the landscape has moved over 500 meters, so my camera position errors are effectively about that high too.

Given this landscape movement and the photogrammetric challenges it causes, this project is a bit of shakedown on new methods in preparation for larger projects next year studying the changes causes by crumpling as the ice gets pushed around. The good news is that despite the motion, I capture 36 million measurements per photograph, and I know that each of those 36 million pixels is undistorted with spatially-correct orientations between pixels. The situation is quite different from lidar, where each measurement is essentially independent of the other. That is, I’ve got a bunch of photographs capturing the landscape, and all I need to do is shift the photographs in such a way to simulate the case in which the landscape was not moving as the photogrammetric equations don’t know the difference, and this is something that cannot be done with independent laser shots. So on the ground we had several survey-grade GPS running continuously to track ice motion and we had several strain meters measuring distance between targets, run by Andy Monahan of UAF and Chris Polashenski of CRREL who are leading the sea ice science that will utilize the topographic maps I’m making, which among other things will help improve our understanding of wind pushes against pressure ridges to move the ice and create even more crumpling. I also employed several tricks in the air that I believe will yield a solution on par with what I get on land, but all this remains to be tested as I only got back from the field yesterday. So we have options in terms of processing, and that’s where the next challenge lies.

The flying and photogrammetry acquisition moved forward without a hitch. It was a beautiful day, with clear skies and light winds. I fortunately timed my flying inadvertently during a lull in other air traffic simplifying things further. I found the sea ice itself fascinating to look at – the shapes, patterns, textures, and complexity were mesmerizing in a way. And to consider the enormity of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean – my view in any direction for probably 50 miles was sea ice, but this extended for 1000s of miles beyond my sight. With that in mind, it’s not hard to imagine the impact of sea ice on the earth’s energy budget – it’s like covering the entire Arctic Ocean with a shiny mirror which reflects sunshine back into space rather than absorbing it. Over the past several decades, the late summer extent of this sea ice has dropped to cover only about half as much as it used to, and we may soon see a completely ice free Arctic Ocean in summers. Such conditions allow the entire Arctic region to warm faster than than the rest of the planet (this is where most of the planet’s recovered greenhouse energy is going) and the lack of a protective ice cover allows storms to create much large waves which leads to increasing rates of coastal erosion in northern Alaska, tens of meters per year! We’ve been tracking the rates of this erosion caused by this process using fodar, and we recently published this paper on it, so it was interesting to me to get so far from shore to better understand the sea ice aspect of these dynamics.

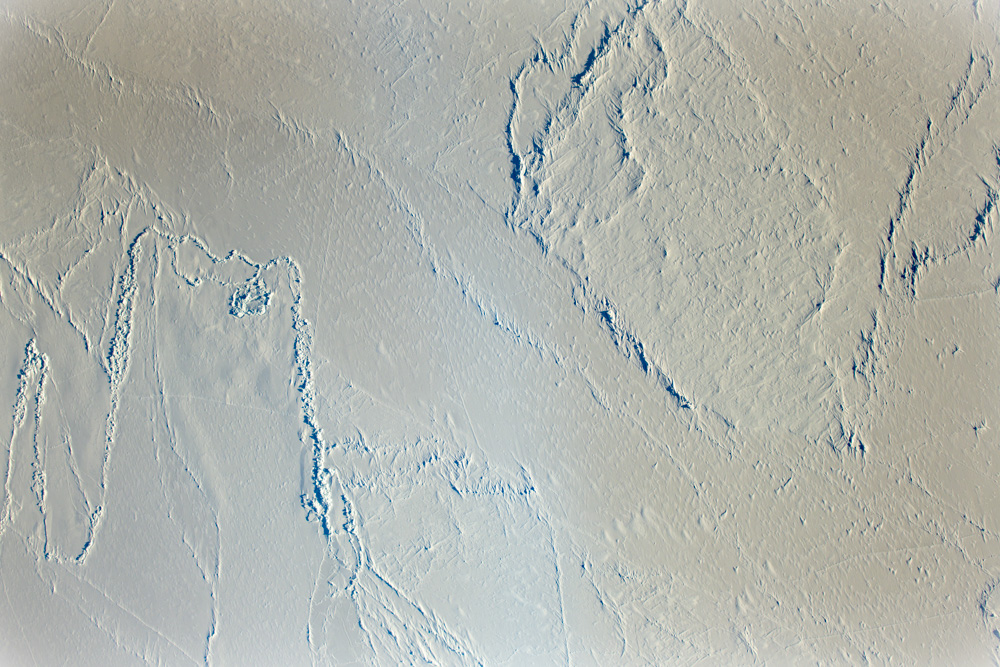

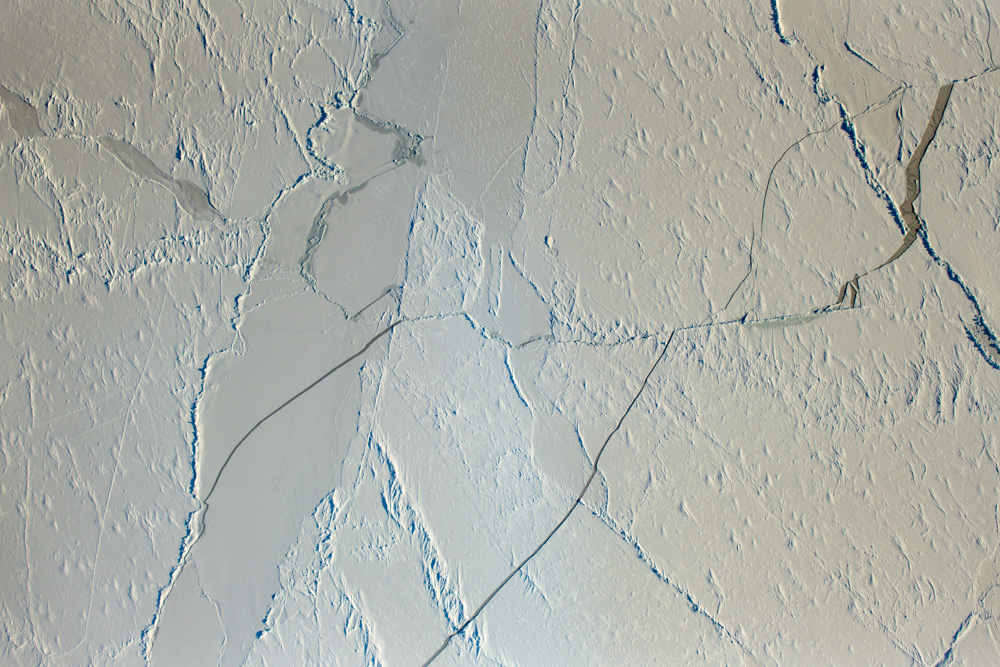

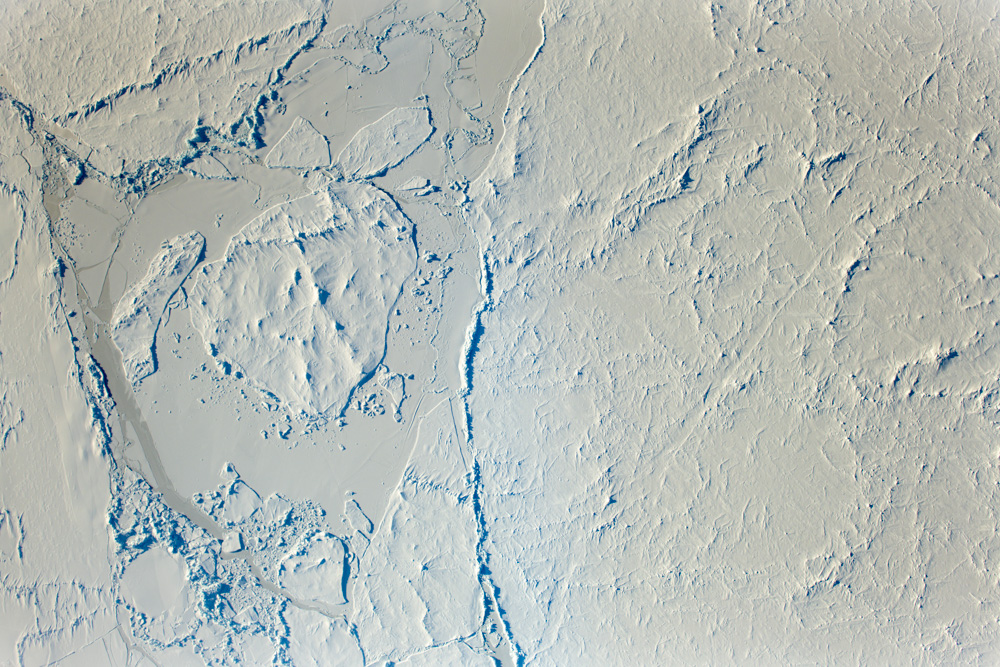

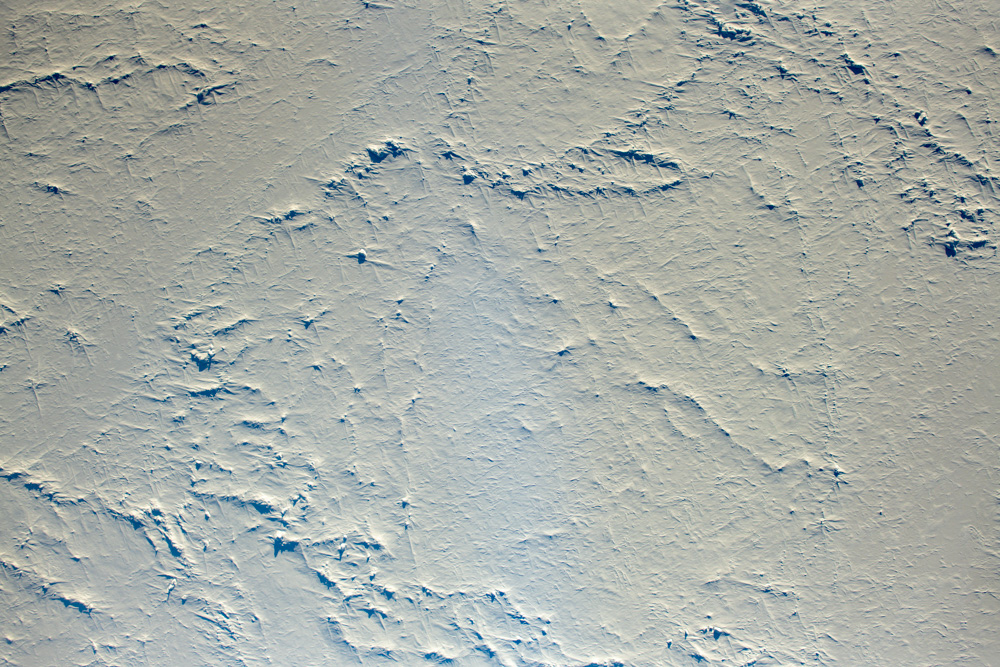

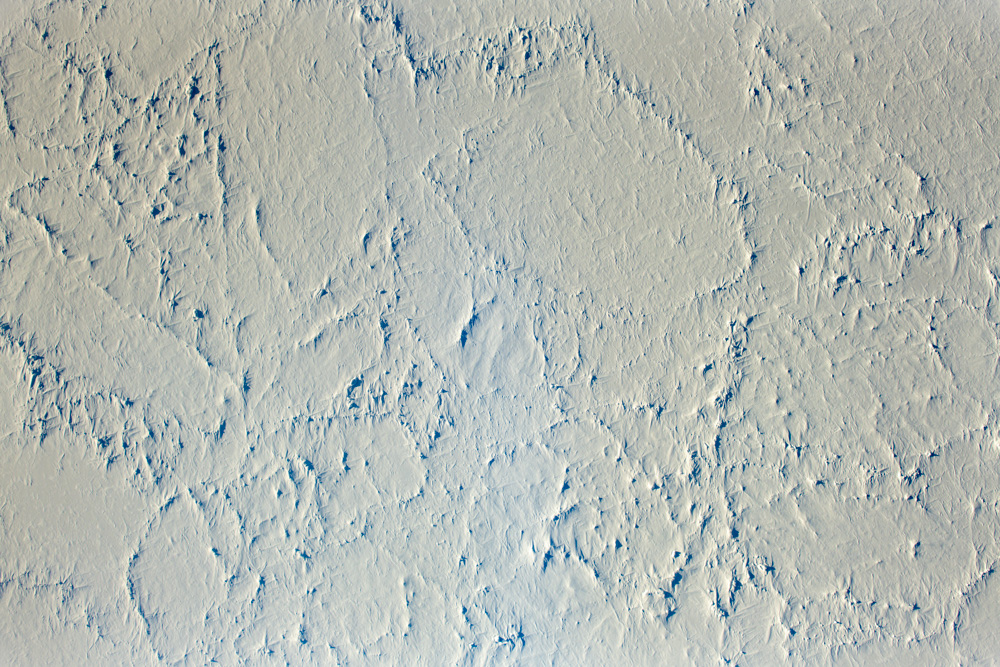

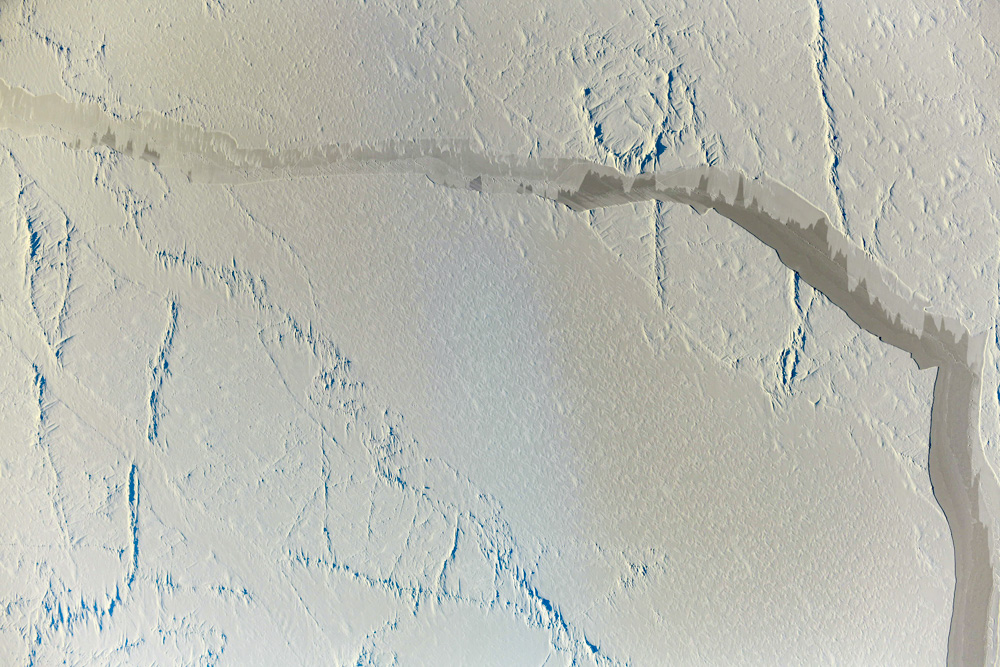

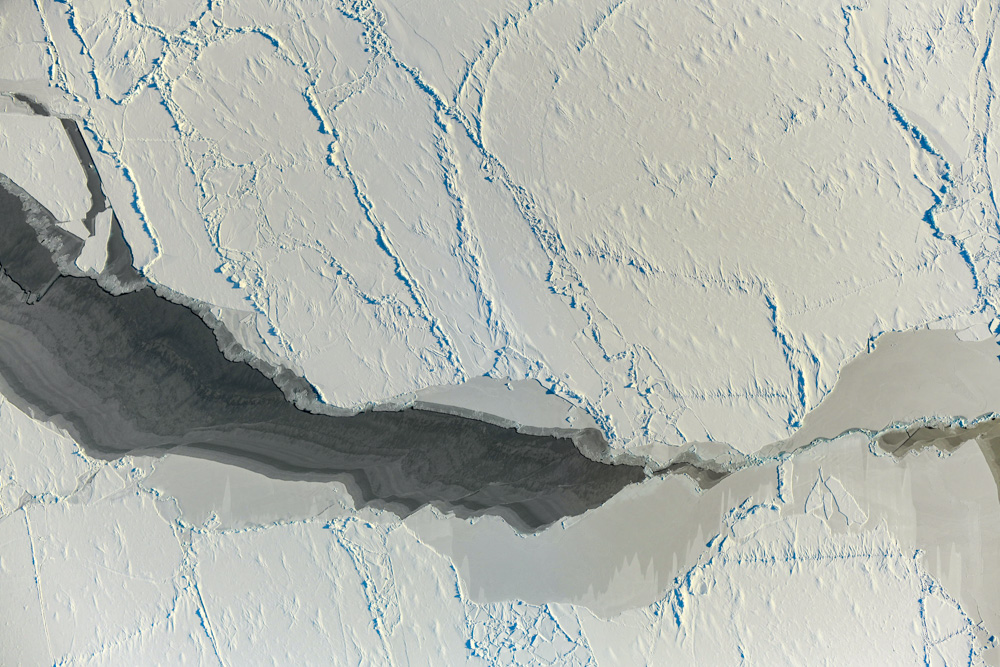

Below are some sample vertical images that will be used in making the map. The images are roughly 7 km wide with a resolution of about 10 cm.

After the mission flying was finished, I landed at the ICEX camp’s mostly groomed air strip to splash in some fuel I was carrying and to say hi. Andy met me at the plane and gave me a tour of camp. It seems like quite a comfortable set up, considering the location anyway. The big fear here is of course that a lead could rip through the middle of camp or under a tent at almost any time, so they take quite a bit of care to monitor the ice and have contingency plans. The scenario of camp being torn apart is not just theoretical, it’s happened several times in past expeditions. I think the biggest fear here is that the runway gets segmented by a lead preventing emergency escapes, so while I was there they were grooming a second runway in a different location as a backup; the onsite helicopter was likely mostly there for this reason too.

I took off again without any issues and the flight back to Deadhorse was largely uneventful. On the way Dean in the CASA caught up with me and passed underneath me just before we reached Deadhorse so I was able to do some air-to-air photography which was fun. I arrived back just before sundown again and once again hangered the plane after fueling, such that I could get an early start in the morning. The weather window I utilized getting up here and doing the mapping was ending tonight, so I was eager to get to Fairbanks before the storm hit.

Well, I did get an early start, but not quite early enough. The weather in Deadhorse was still great for leaving, but I was glad to not be flying over the sea ice today. There was a high overcast and some mixed cloud layers to the north that looked like it made for some flat light and potential ground obscuration. The lower ceilings were coming in from the west, so I decided to not to follow the haul road but rather to fly east over Kavik and take a pass in the Canning River valley to cross the Brooks Range. I waved as I flew over but didn’t land as I was in a hurry, making it onto the south side with enough ceiling to fly over the terrain, but only just. I landed in Ft Yukon to check weather to the south and splash in some more gas. Fairbanks weather was getting marginal, and I could see ceilings were dropping rapidly to the south. After filling up (thanks Kirk!)to maximize my ability to divert around whatever I needed to, with 7 hours of fuel for 1.5 hours of direct flying, I launched south to see what I could do.

I tried Beaver Creek to the southwest first, but got turned around due to no visibility, with white mist and snowfall blending perfectly with the snow covered ground. So I turned east to follow the edge of the White Mountains and look for a different drainage to follow. I poked my nose into several drainages with the same result each time – as I got towards the head of the valley, the white terrain merged with the white sky ahead of me such that I no longer could distinguish them and I was not quite able to fly high enough to clear the terrain. I made it out past Circle Hot Springs before I eventually turned around to head back to Ft Yukon. I was tempted to land at Circle Hot Springs, I could see the pool was full, but Kristin told me by satellite text it was still closed, which was too bad for me. As I headed back, the higher ceilings I enjoyed on the way here had disappeared, and I was flying low in the mist, using the tree tops for a horizon. By the time I reached Ft Yukon I felt done with flying for the day and began sorting out a place to stay and putting the plane to bed.

Ft Yukon is a village of about 600 people, most Gwich’in locals with a mixture of other indigenous groups in part due to the presence of an orphanage here in the past which served many Alaskan indigenous groups. There are no hotels, restaurants, or airplane services here, as there apparently were 60 or more years ago, but I found a place to park and a bedroom in a bed and breakfast run by Ginny Alexander. I spent two nights there waiting on better weather, and it was a delightful experience to get to know the community better, as previously I had never made it off the airport grounds. Ginny is married to Clarence Alexander who was the tribal chief for many years and very active in community organization and advocacy especially in the 1980s through early 2000s, though still active today at 80. He spent several hours at breakfast telling me stories of the community and Ginny pulled out several photographs, such as him shaking hands with Obama after getting a citizen’s award. The community here is very closely tied to the land. The people here are resourceful and seem to take pride in providing for themselves and taking care of their community, and they live modest lives in small cabins and houses, where keeping up with the neighbors in terms of appearance is just not a dynamic, here function dominates over form. The house I’m in right now is maybe 1000 square feet, with 3 bedrooms and 1 bath, where Ginny and Clarence raised their 5 kids, who went on to be become professors, accountants, magistrates, and community leaders, reinforcing the idea that material wealth and success in life are not necessarily correlated. The Gwich’in Steering Committee has been very active in recent years in protecting the ecology and spiritual values of the Arctic Refuge from irresponsible decision making, goals shared by Fairbanks Fodar and with similar philosophies albeit from a different perspective.

Though I would have liked to have stayed longer, the weather was beginning to improve by Monday and other poor weather was on the way. The regular air traffic into Ft Yukon on Monday was also able to provide me weather observations available no other way, and the friendly pilots at Wrights and LifeMed let me know that the ceilings had now lifted substantially compared to yesterday and that the mist we were surrounded by topped out at about 4000’. So I packed up the plane, which I kept heated by plugging into Kirk’s power, and blasted off. The weather was far from perfect, but it was a perfect end to my furthest north adventure in the Arctic. Now to process some cool data…