Two-One-Charlie vs The Big One

After two weeks of effort, flying over 6000 miles and acquiring over 35,000 photos, we have now nearly completed acquisitions for the most detailed and accurate topographic map of Denali National Park and Preserve yet made. This blog tells that tale.

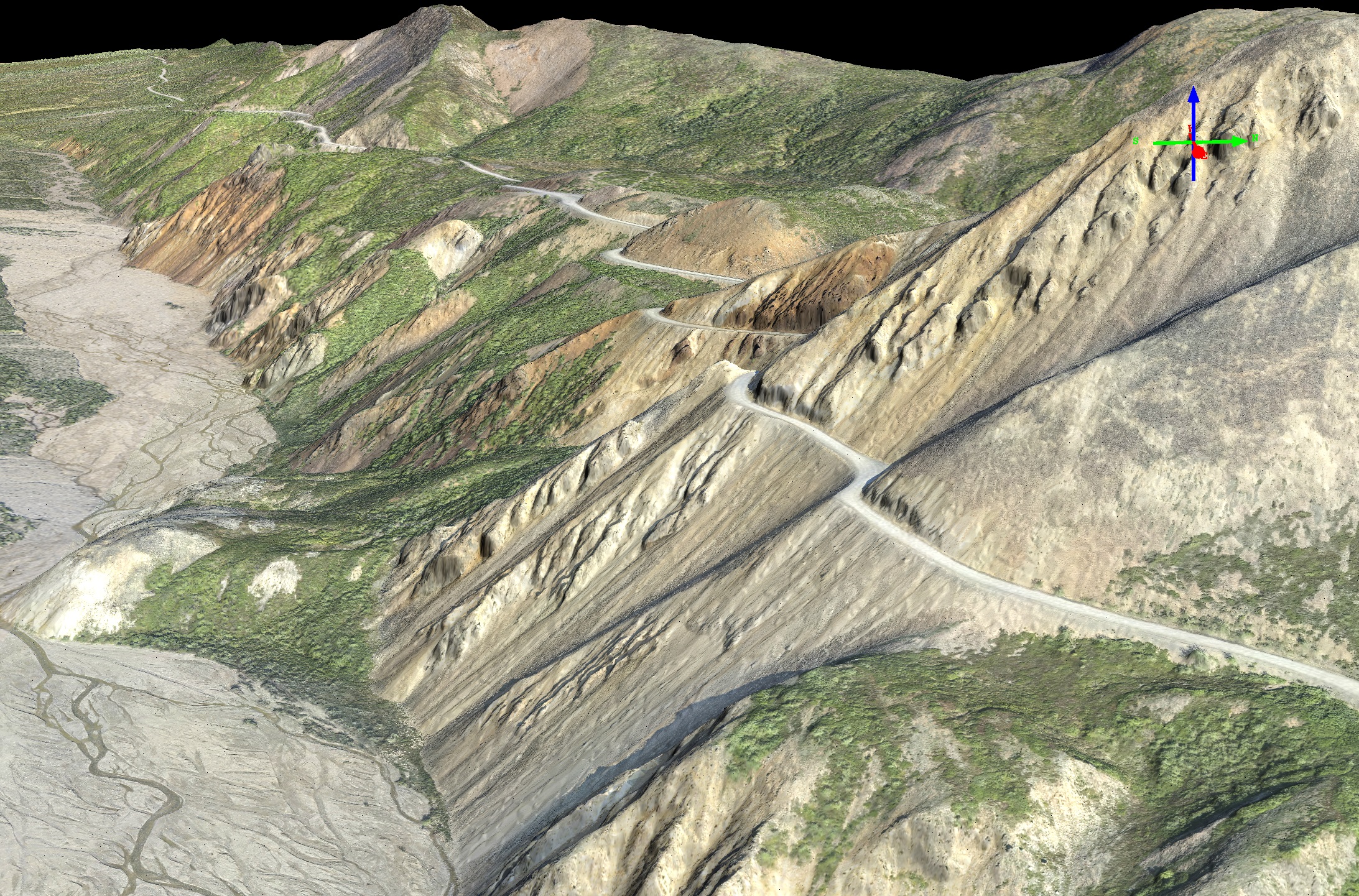

The project is largely focusing on the watershed of the park road, which carries over half a million visitors each year within the northern shadow of Denali, also known as Mt McKinley and The Big One. The road is subject to washouts and landslides, so more study is required to understand the overall dynamics as well as accurately map the road and the changes to it. Also included in the area are bunches of glaciers, geology, permafrost, and other features of scientific and public interest. The purpose of the map is not just as a base layer to figure out where things are, but as the first tick in a time-series of such maps to measure how things are changing over time. I had already done several small projects out here, including mapping the entire road at 10 cm, mapping a landslide here several times that blocked the road, and mapping one of the floodplains several times that affects a bridge crossing the road, all for the National Park Service that manages these lands. Based on the quality and positive reception of these results, the bigger project was born. The project was funded late last summer, so I’ve had the winter to psych up for the contest of 21C vs The Big One.

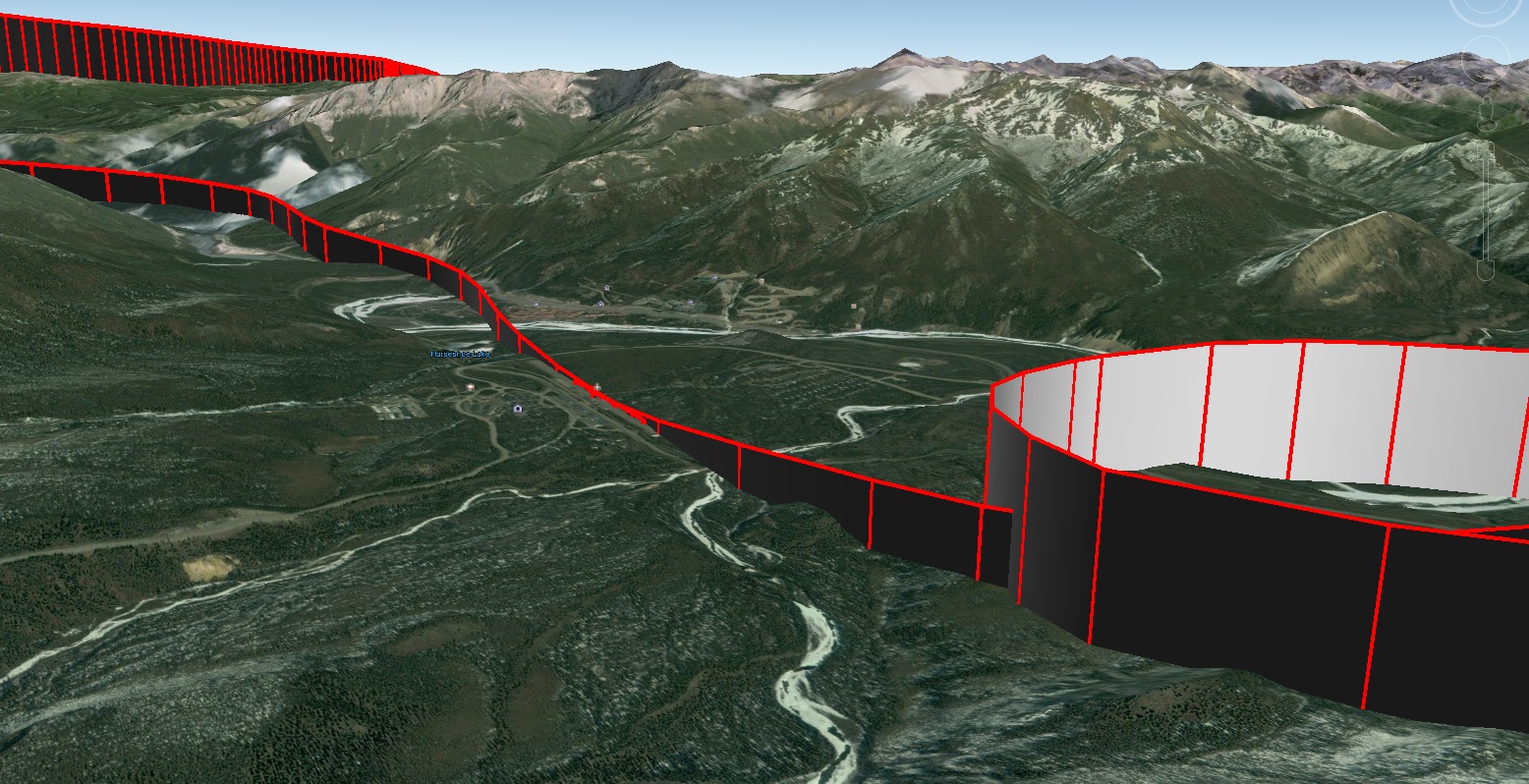

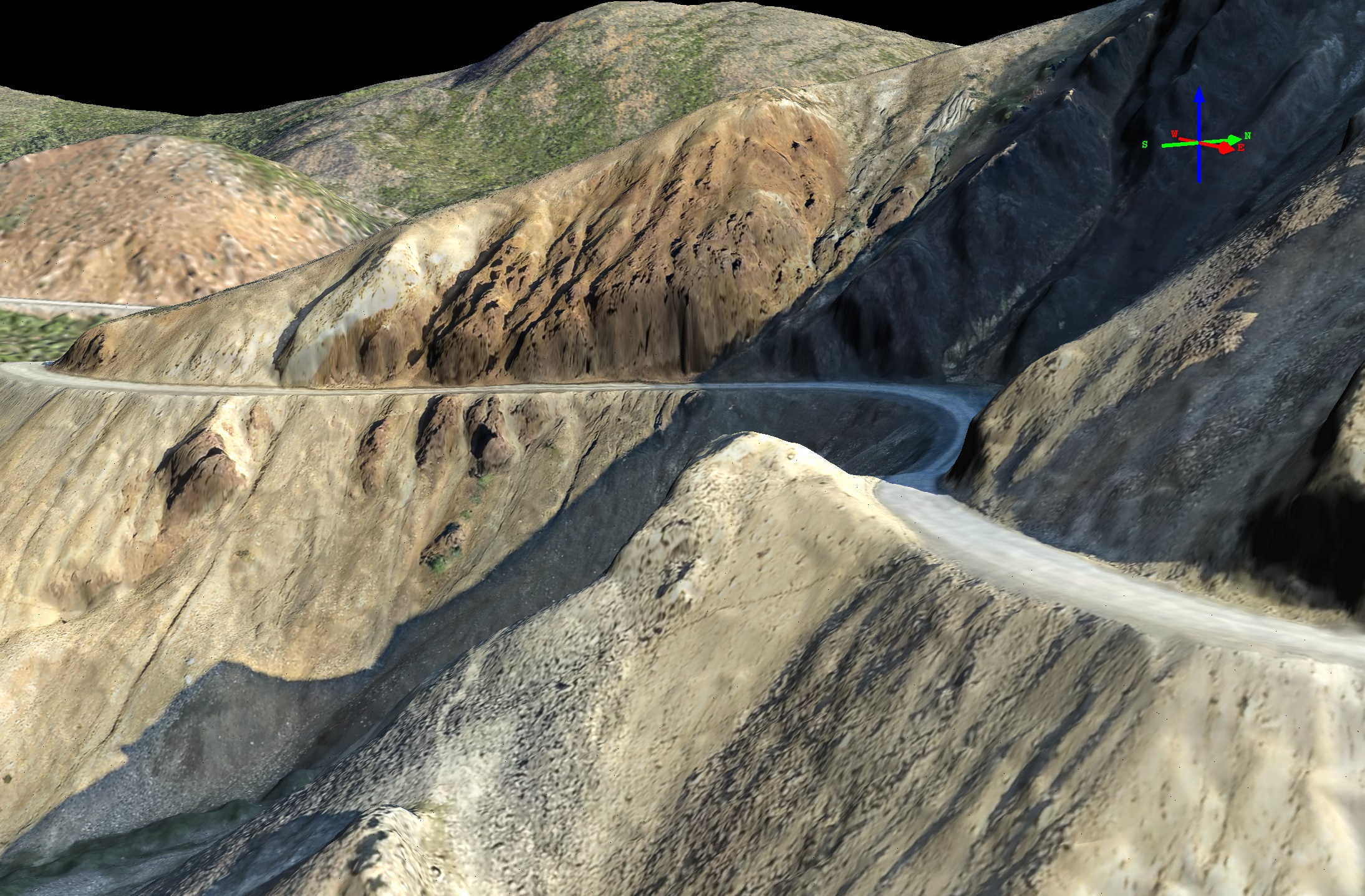

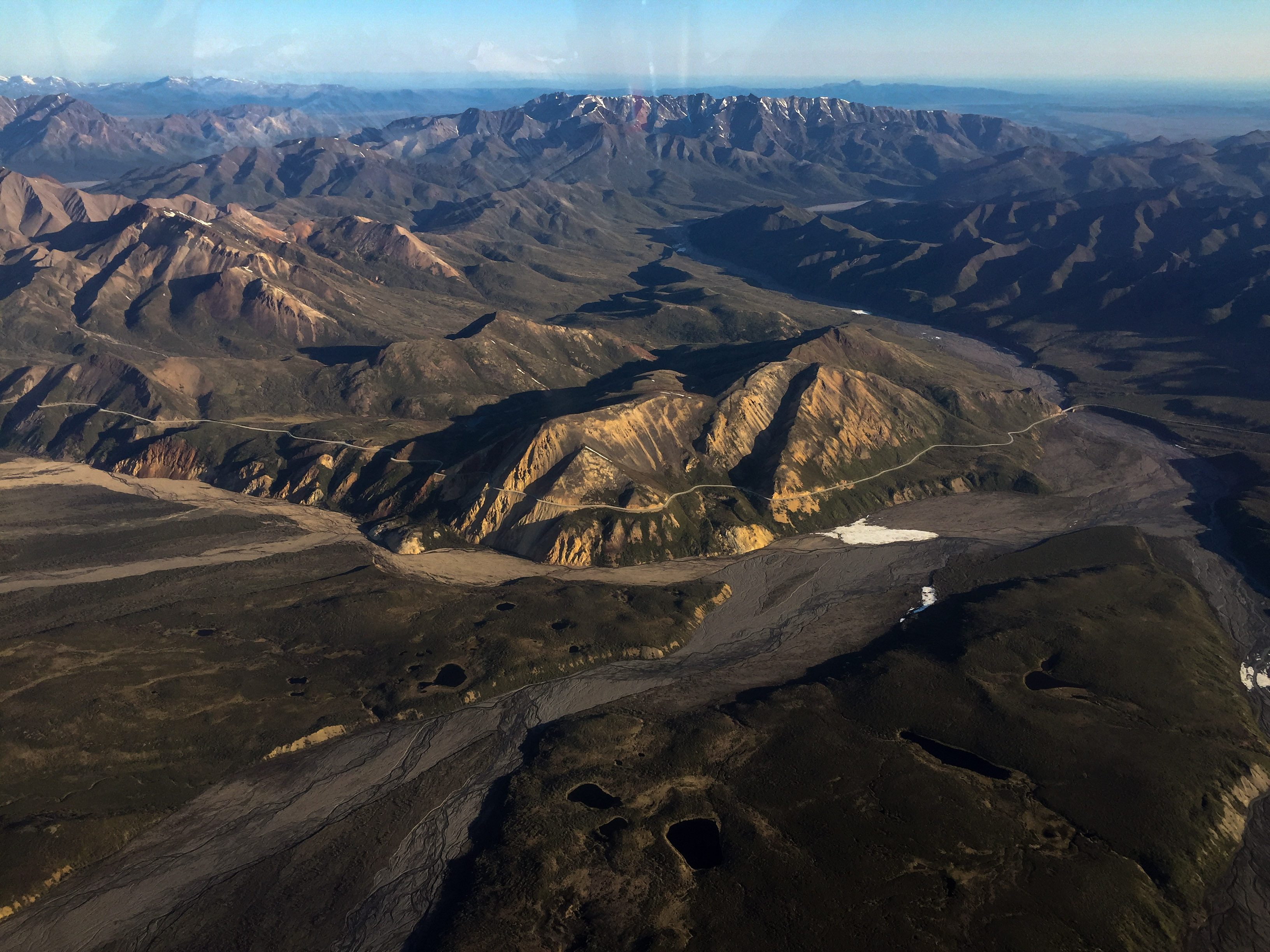

The park road winds its way along steep hillsides, as imaged here by fodar from 2014 at about 10 cm resolution and accuracy. Note that not only is road accurately imaged, but even goat trails can be mapped.

Dozens of tourist-laden buses pass over this road per day to explore the wilderness here. Keeping the road open and safe is thus an important mission for the park staff.

Here you can see a small landslide that we mapped twice, in August 2014 and June 2015; mouse-over to flicker between them. Slides like this not only block visitors from entering the park, but trap others inside, often for days.

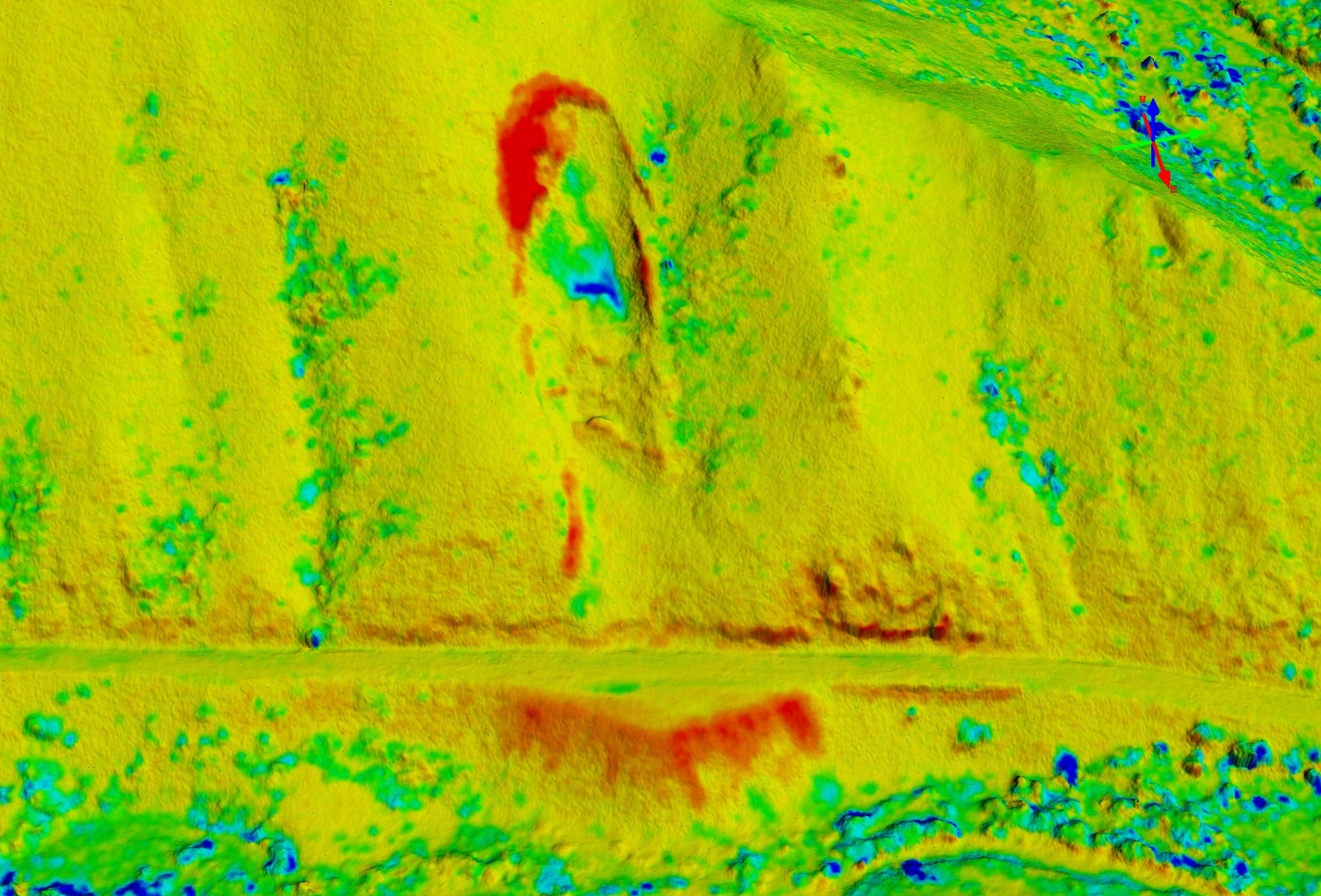

Here is that same slide shown as a difference image draped over terrain, with red colors meaning elevation was gained and blue colors meaning elevation was lost over the mapping interval, mouse-over to see the real color image. Note that debris continues to rain down onto the road. In other work, we have shown that fodar is accurate enough to detect motion along slip-planes before a landslide occurs.

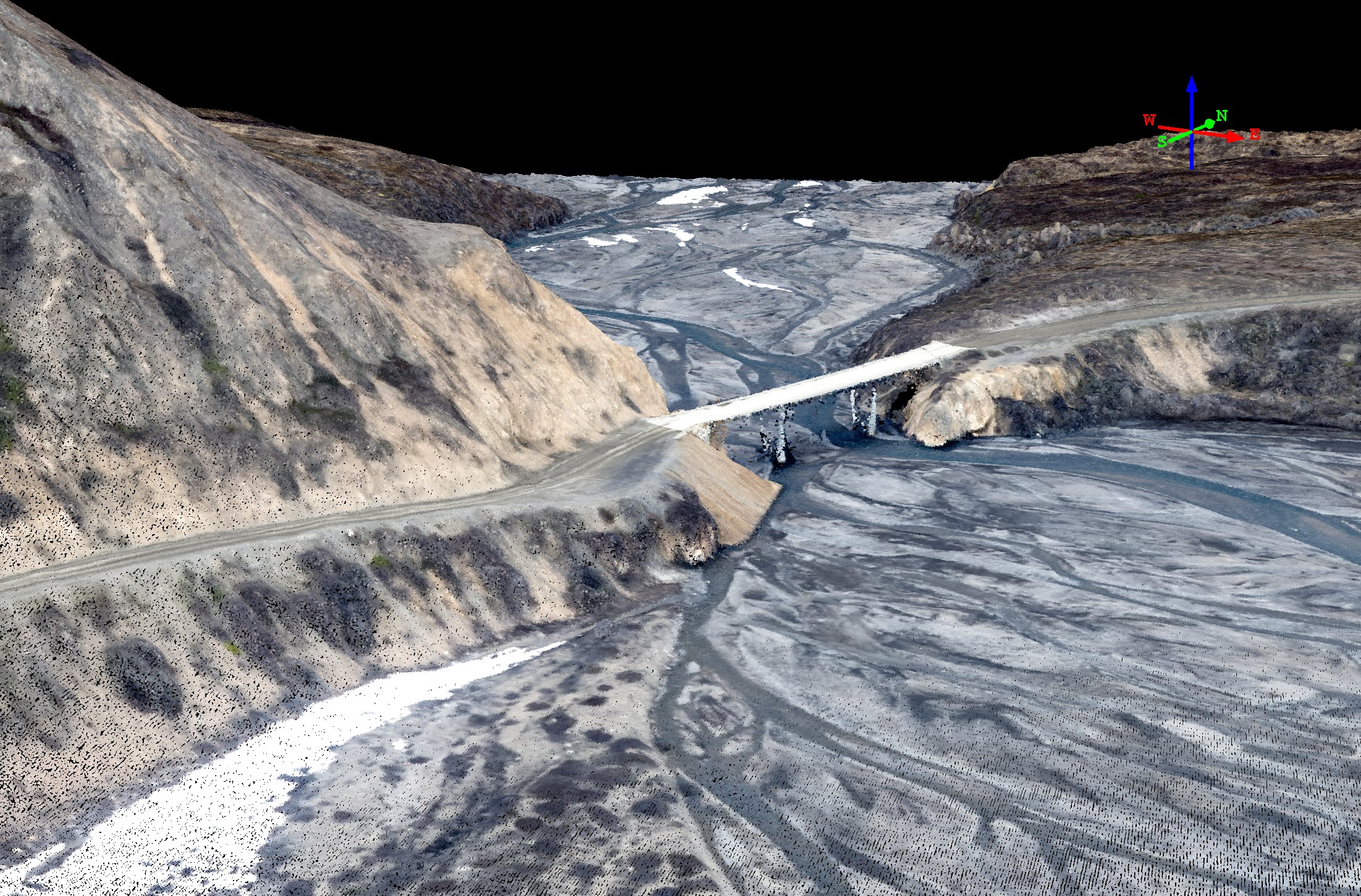

There are several bridges along the road which also require maintenance, inspection, and repair. With fodar point clouds like this one, we can measure scour along the bridge piers over time, among many other things.

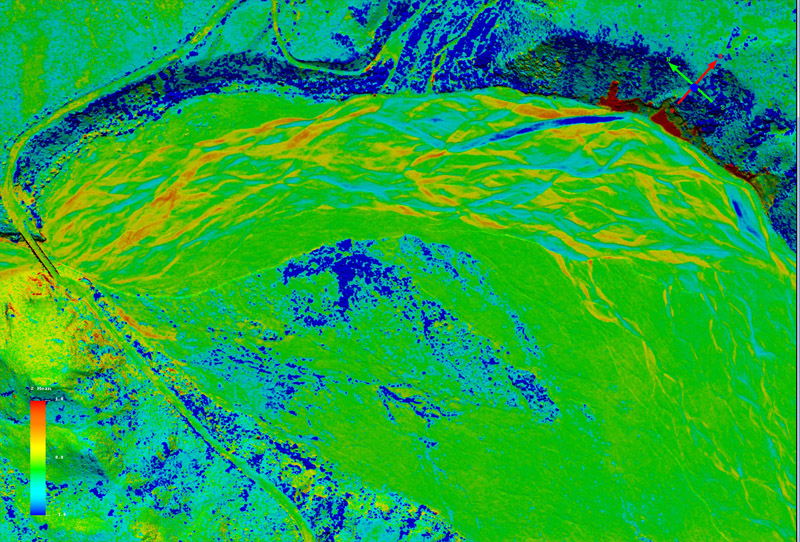

Here is a section of the Toklat River in Denali National Park in early June 2014. Mouse-over to see the same area in late August. Note that the position of the river and its braids has changed considerably. The primary purpose of fodar is to detect change on the landscape, as this is the only technique that is affordable enough and accurate enough to do so over enormous spatial scales at high resolution.

Here is the same area, this time as a difference image of elevations. These are direct measurements of change in topography caused by stream channel migration, deposition, and erosion. Note that fodar does not measure the height of water accurately, so some care is needed to distinguish apparent elevation change corresponding to the water bodies themselves, and much of the change seen here is over either old or new water channels, as seen in the mouse-over. Most of the dark blue is shrub growth.

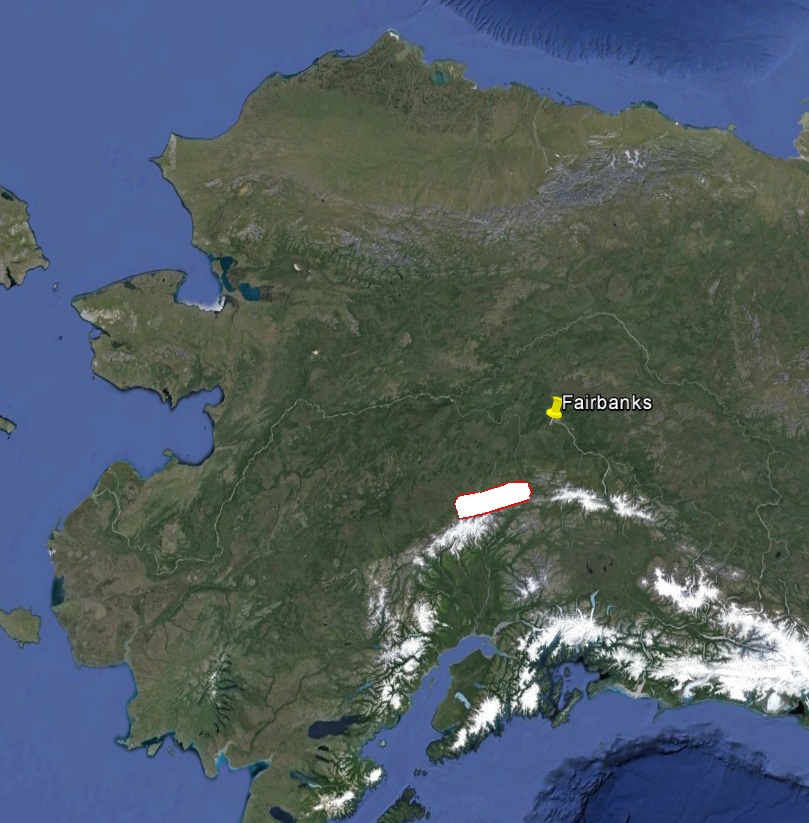

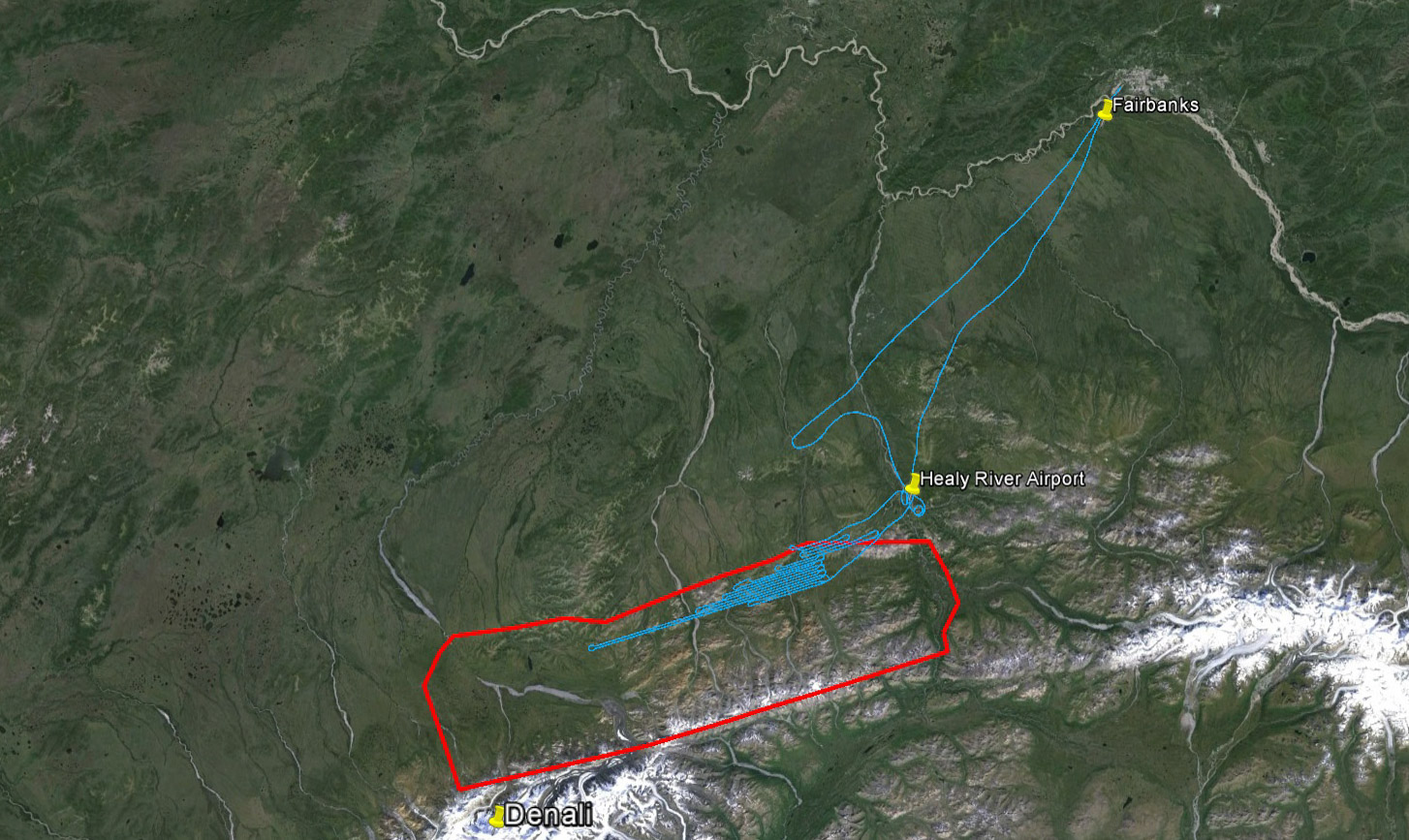

It’s a big area at over 5000 square kilometers. It’s not really clear to me how big the park is, as it’s a mixture of Federal and State land each with various distinctions as Park, Preserve, Wilderness, etc, but my map area seems to be about ¼ of the Federally owned land which I think is most typically associated as being The Park. For context, this is also about ¼ the size of New Jersey, and bigger than Rhode Island, Alaska’s favorite state to pick on after Texas. As planned, mapping it at 10 – 40 cm will require a total of over 50 hours of flying over the site, not including the 2-3 hour commute time from Fairbanks each day and dealing with weather. So that’s a full week of flying 10-12 hour days if the weather cooperates, or a month of fighting it. We had already tried to get this project underway last year, but some contracting delays coupled with an early snow fall prevented us from getting started.

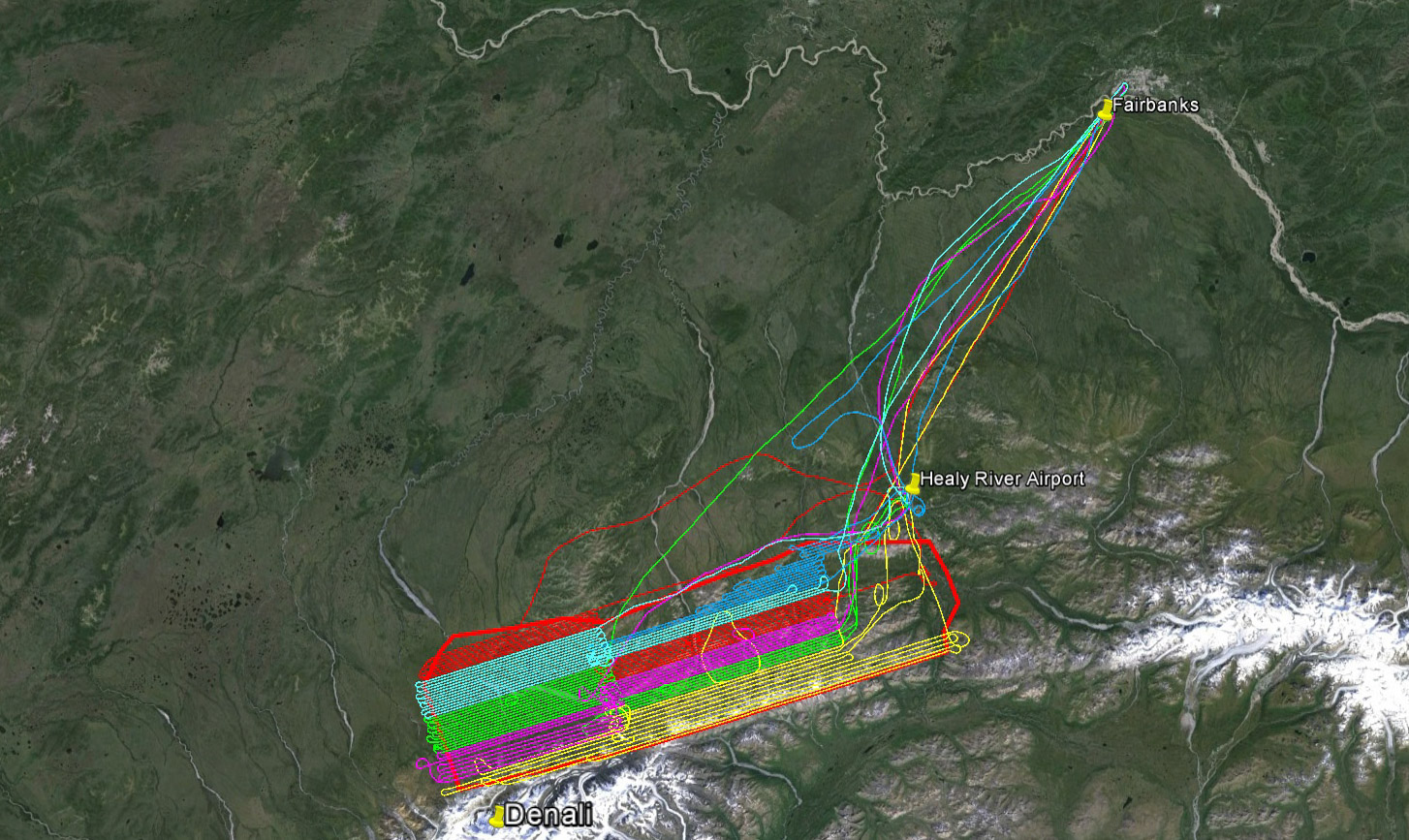

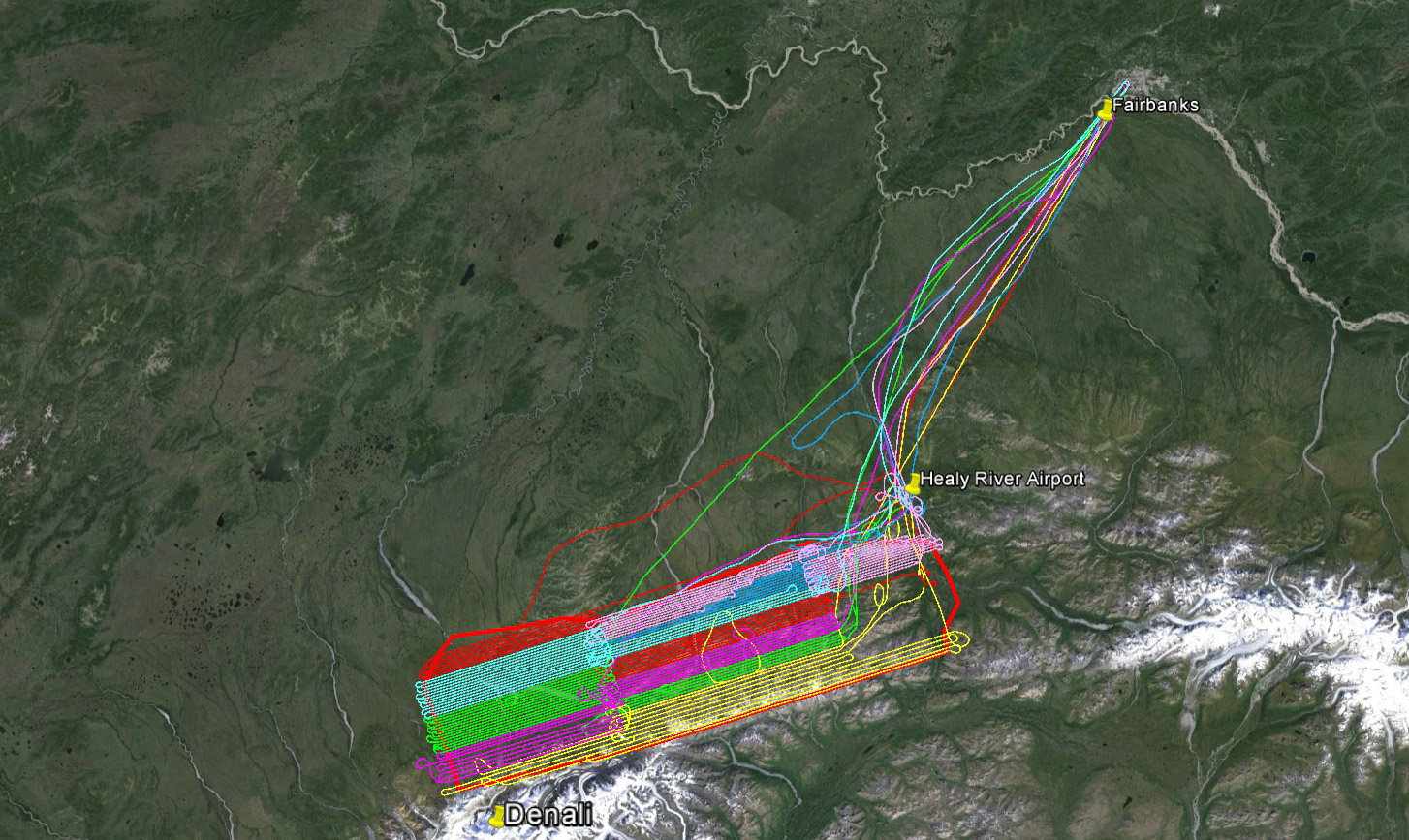

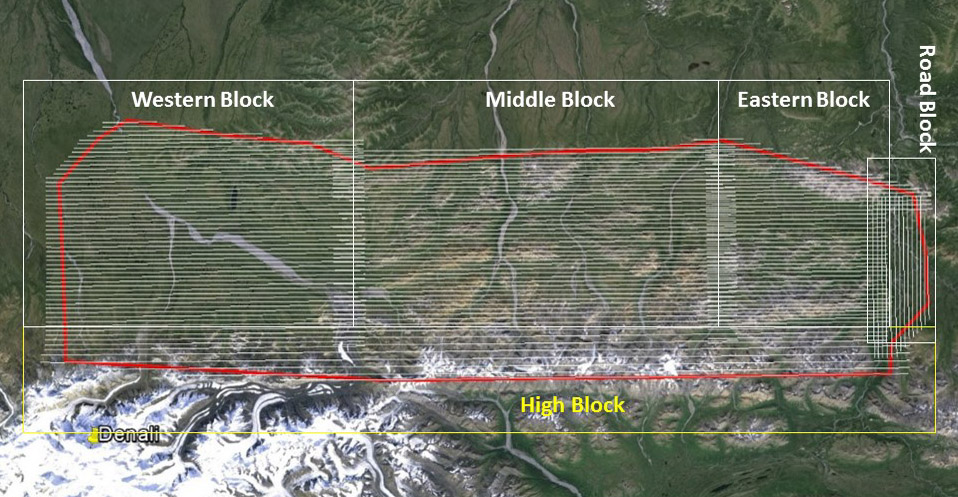

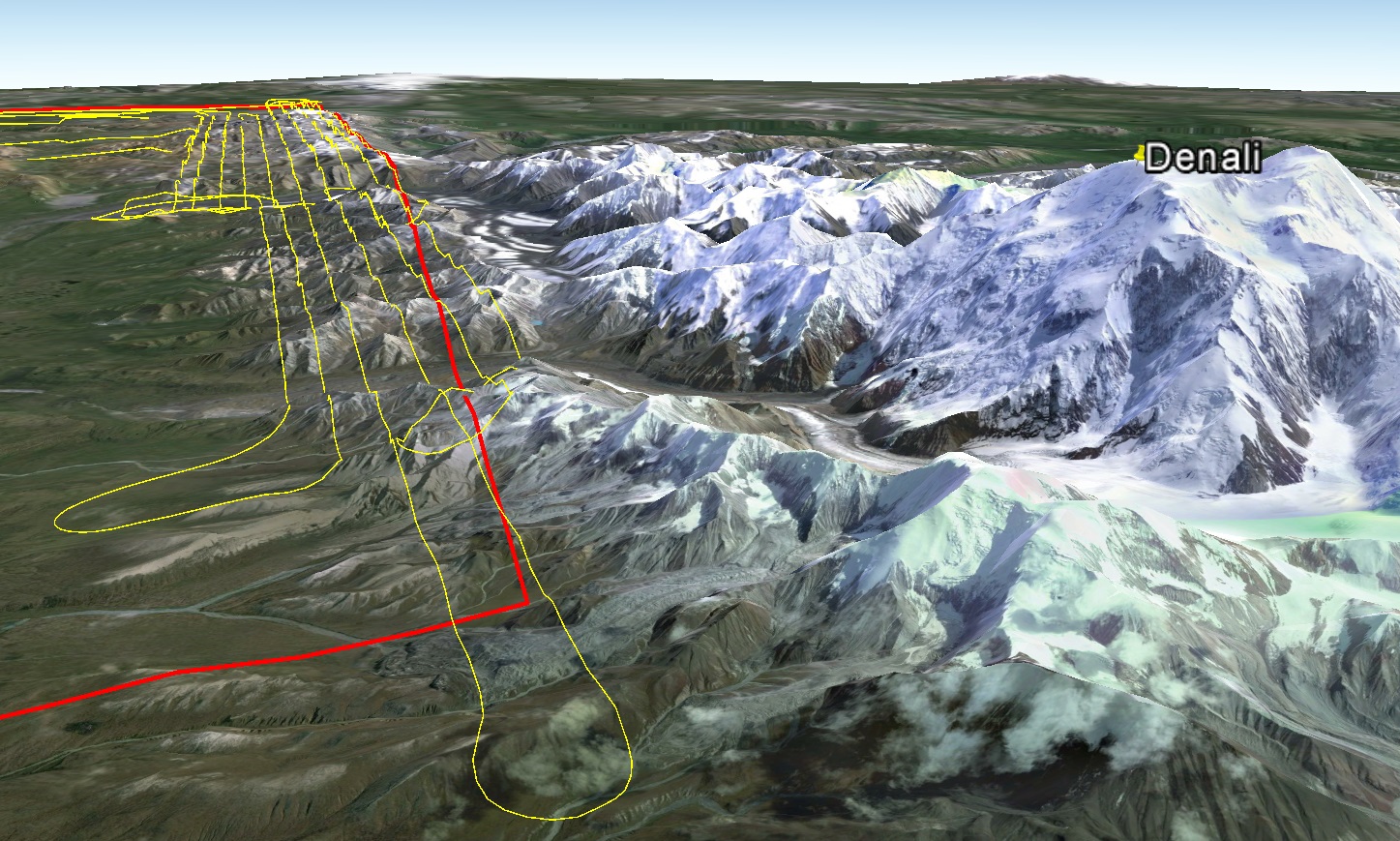

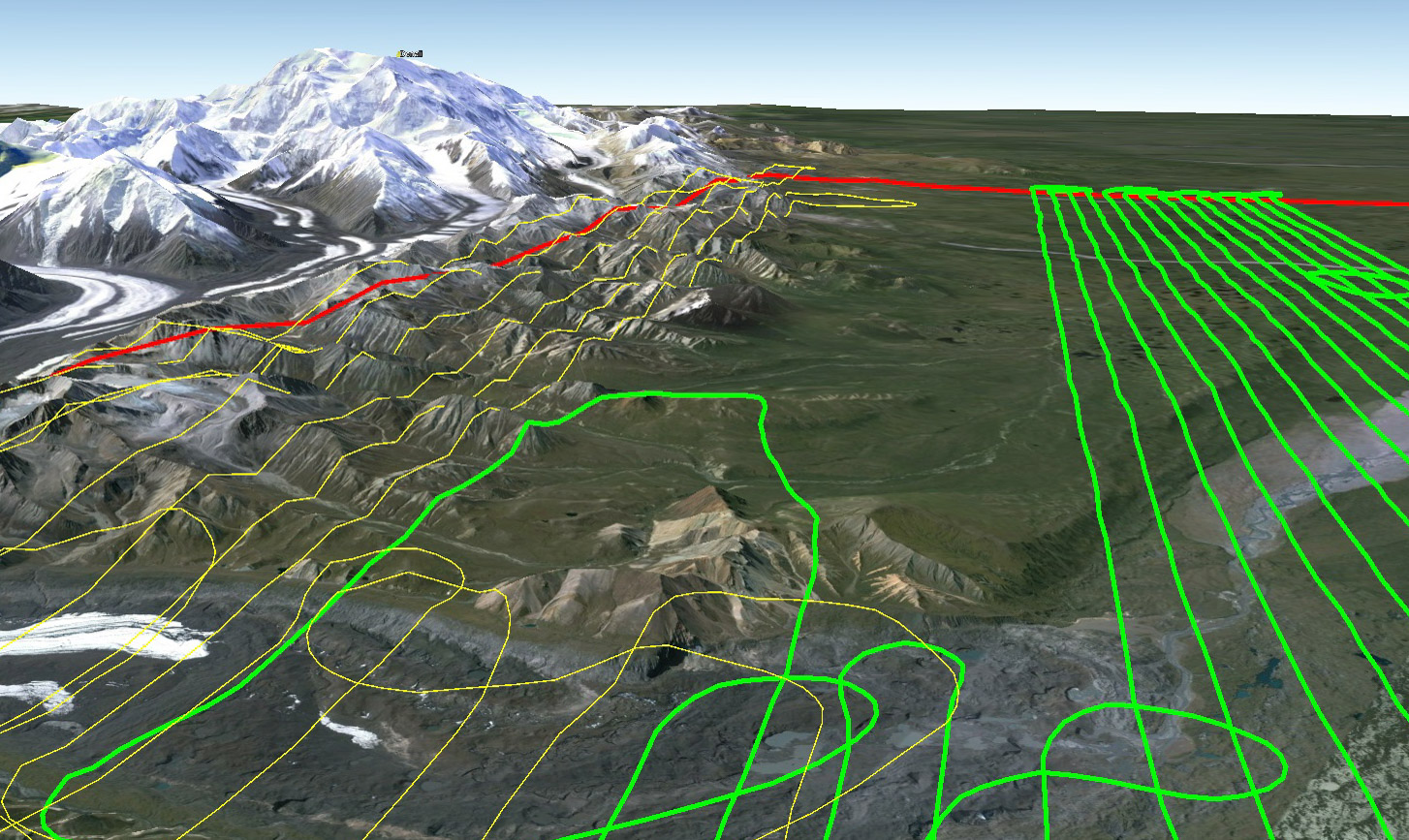

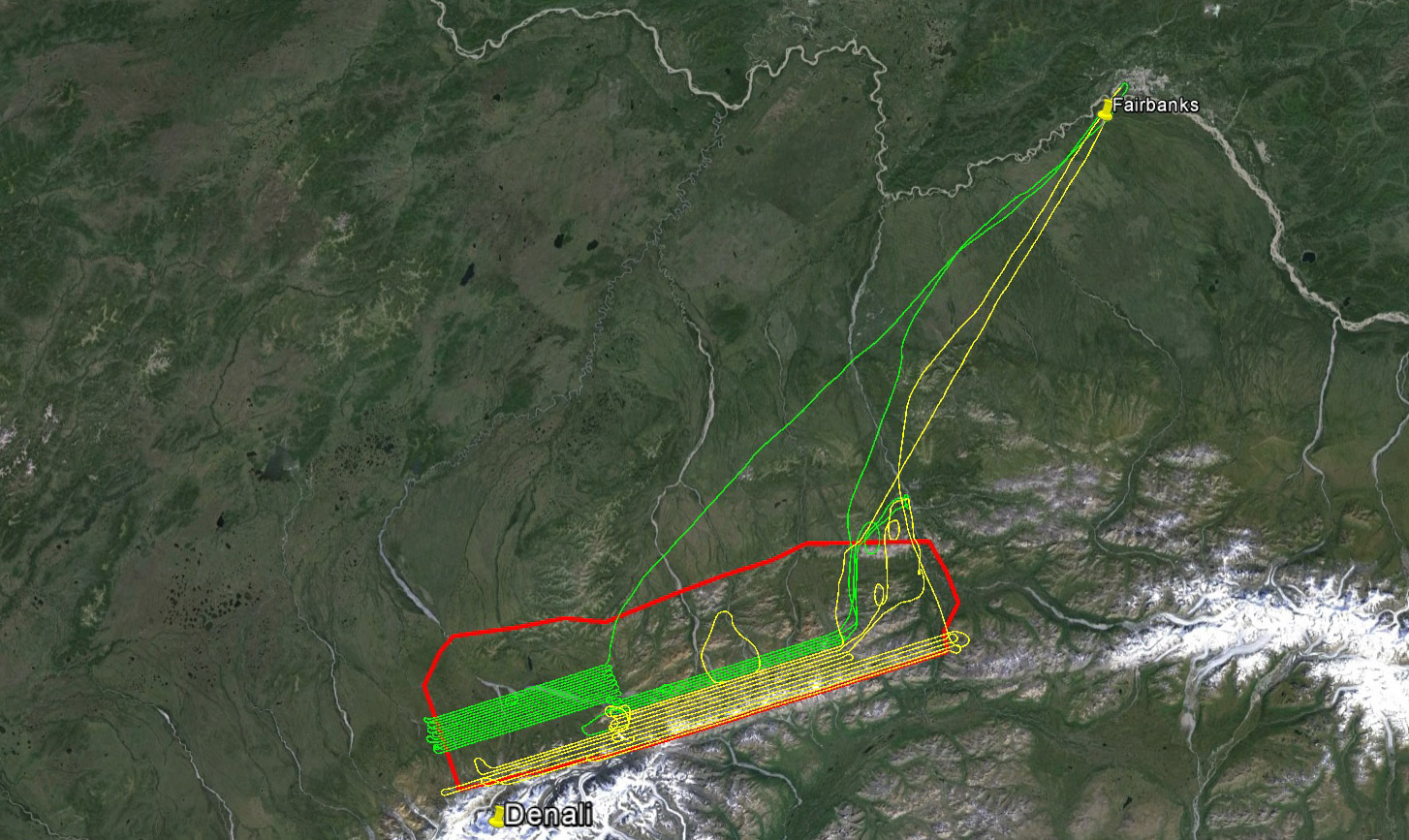

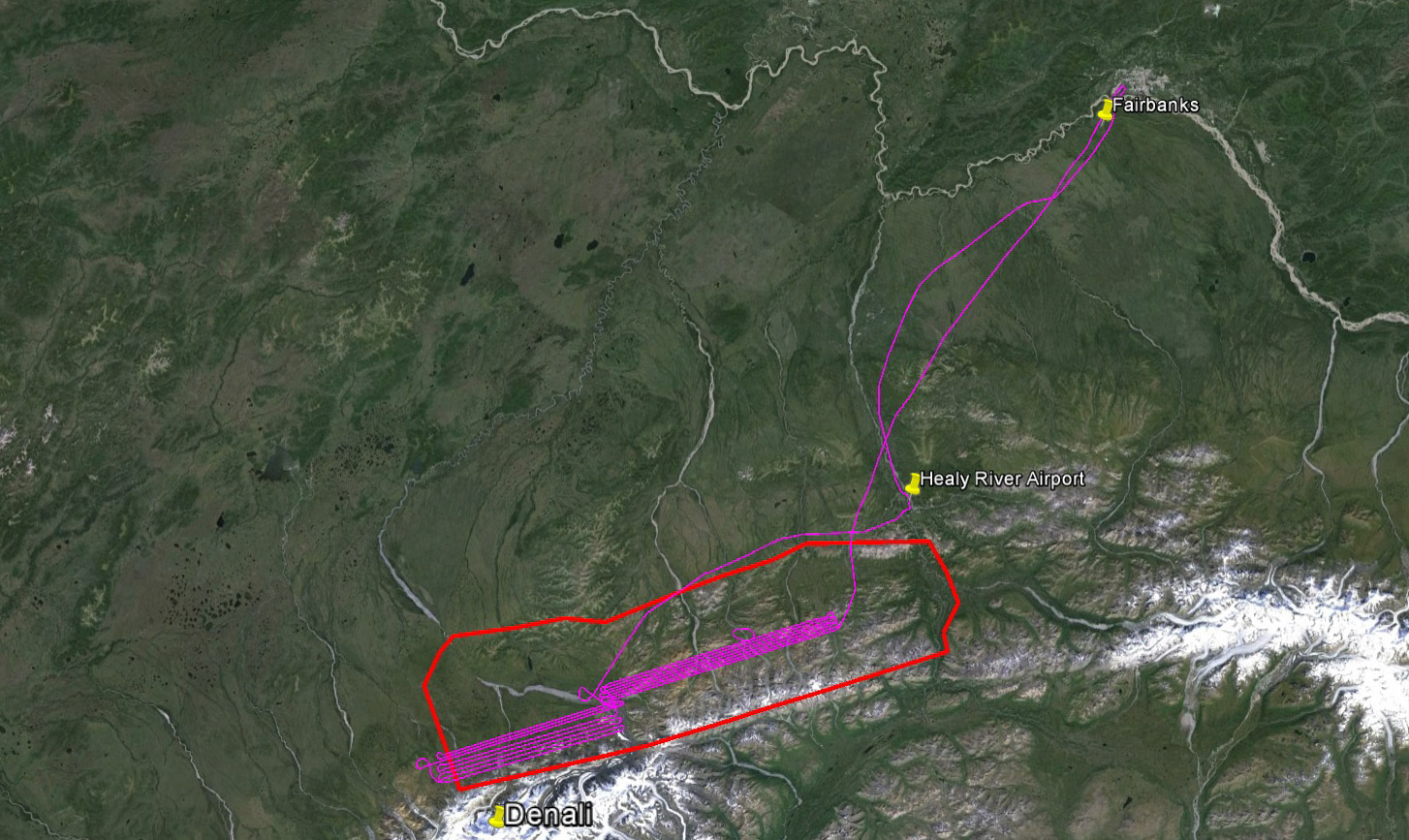

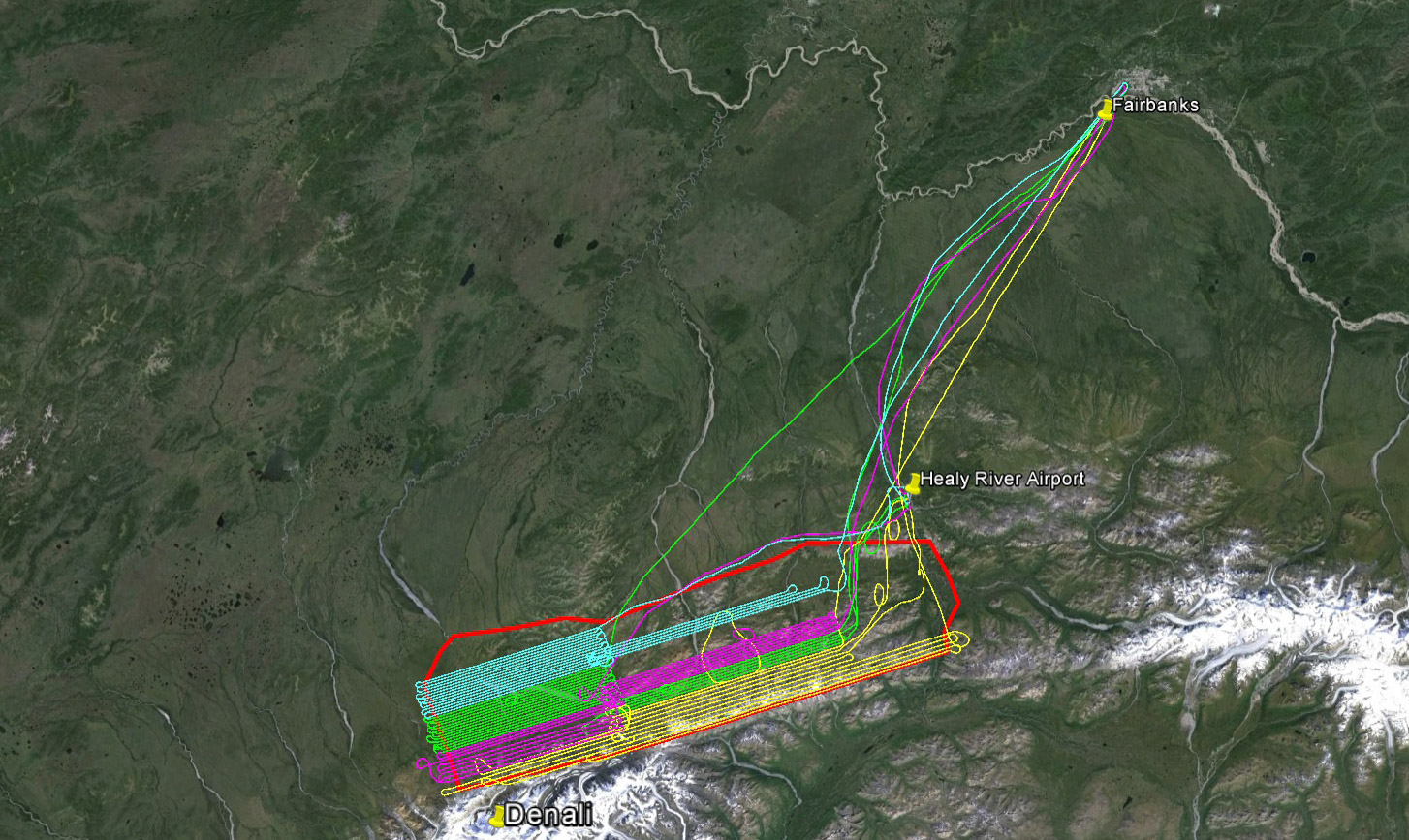

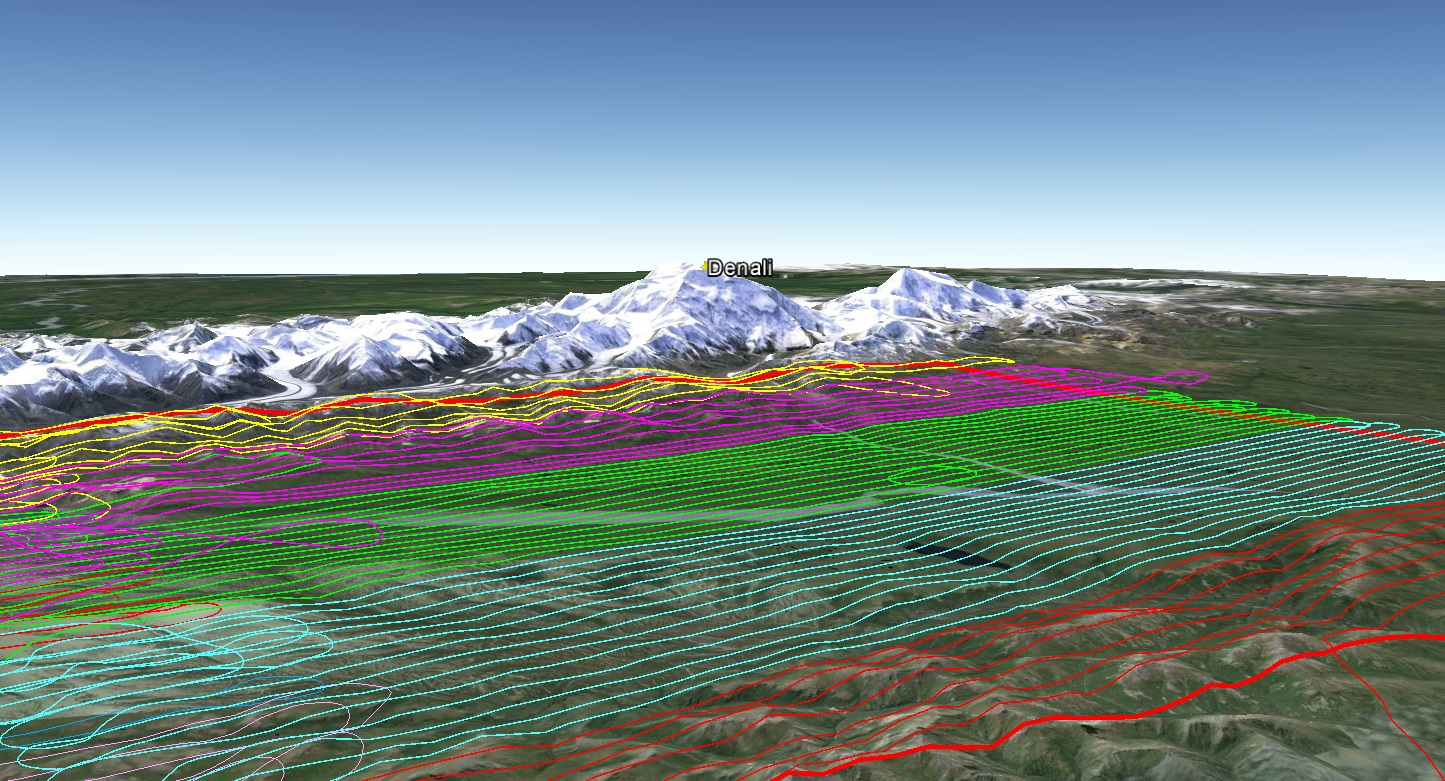

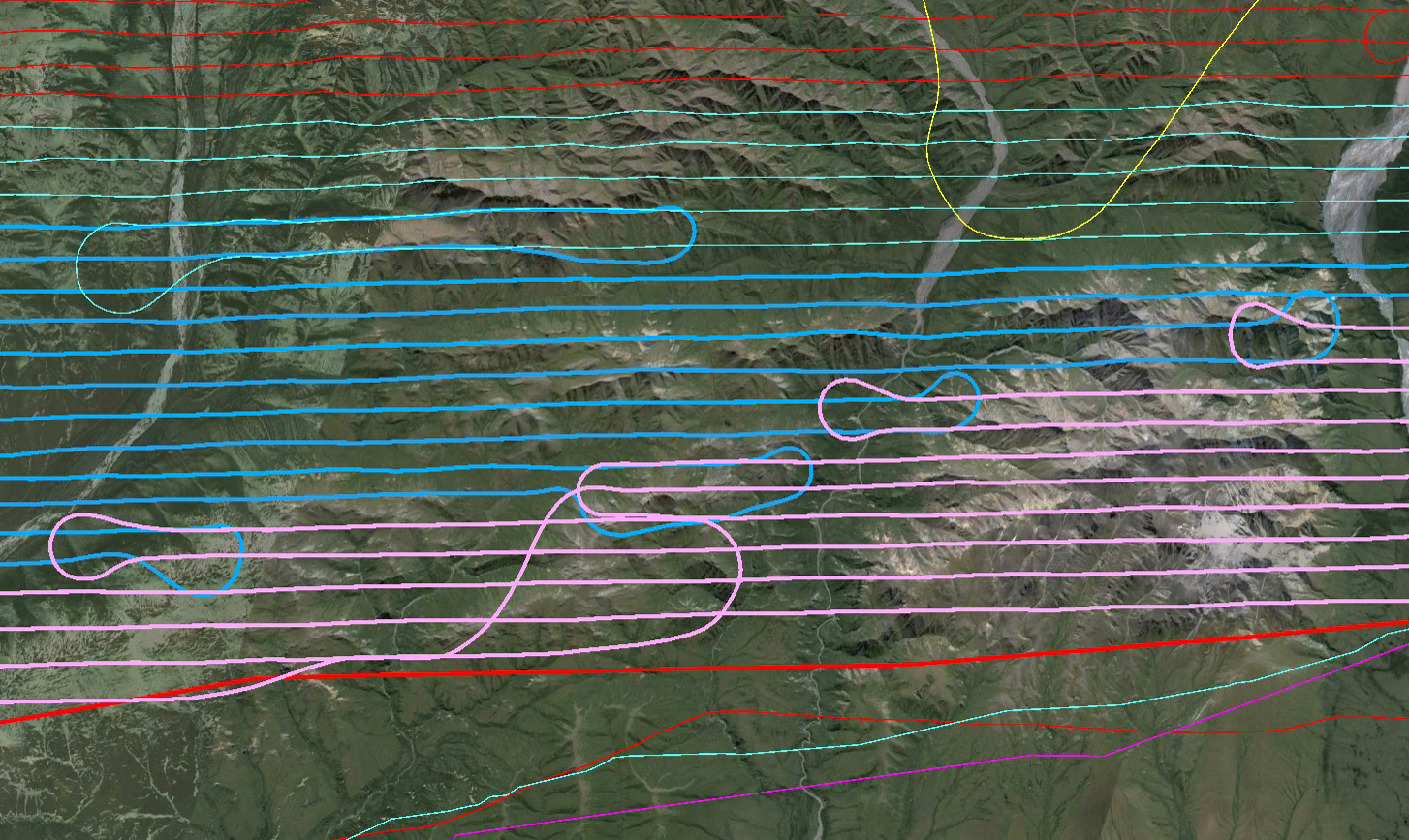

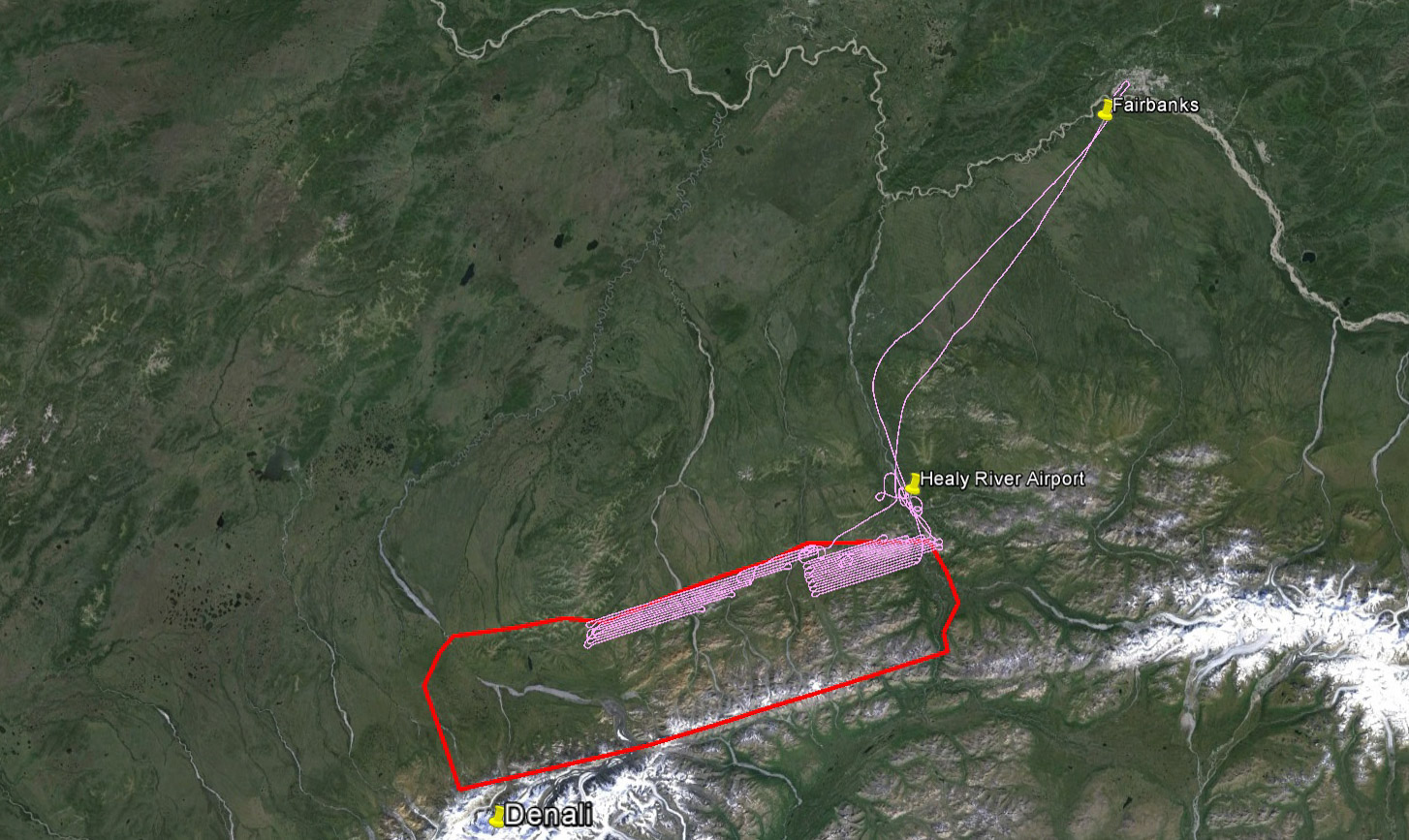

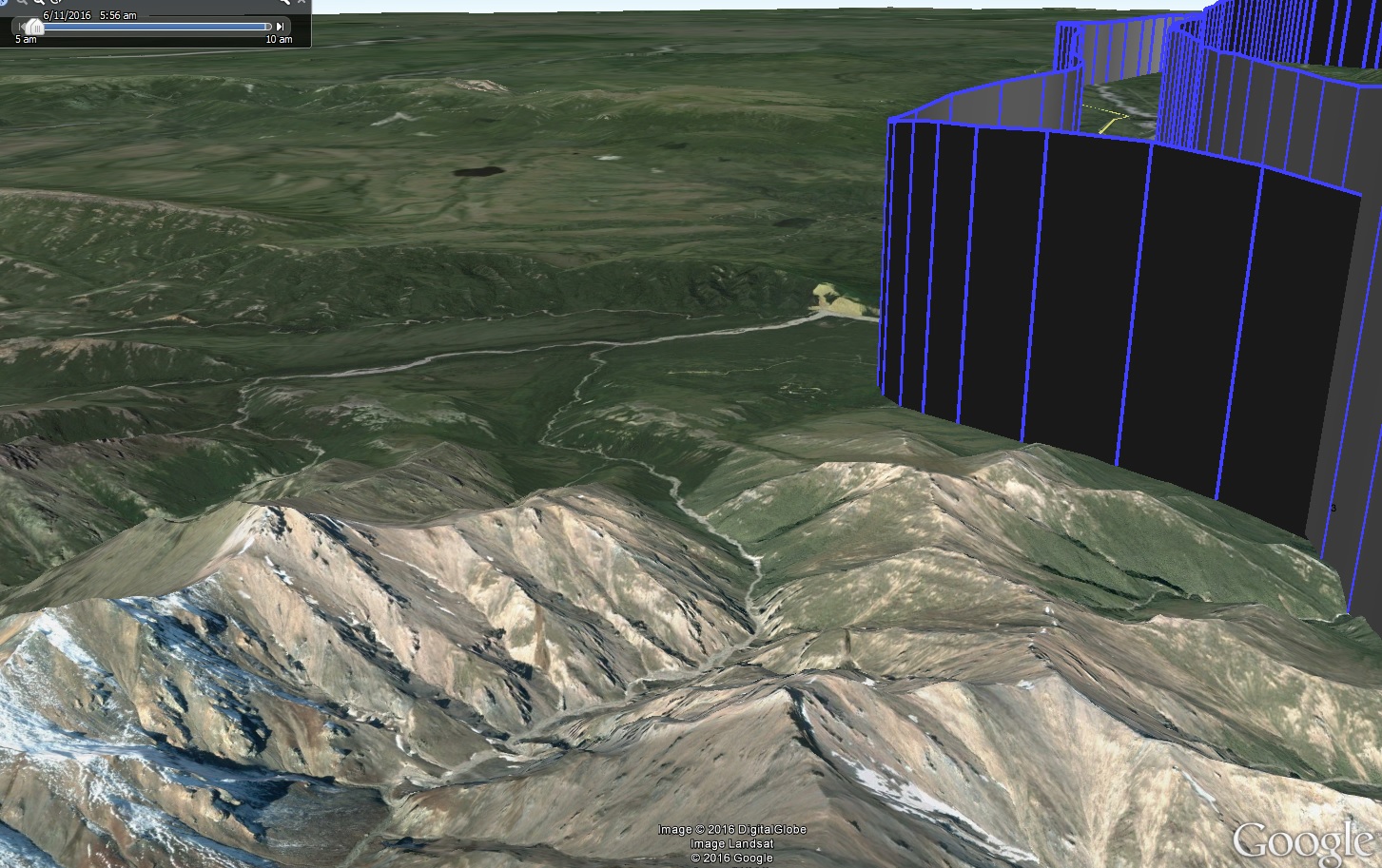

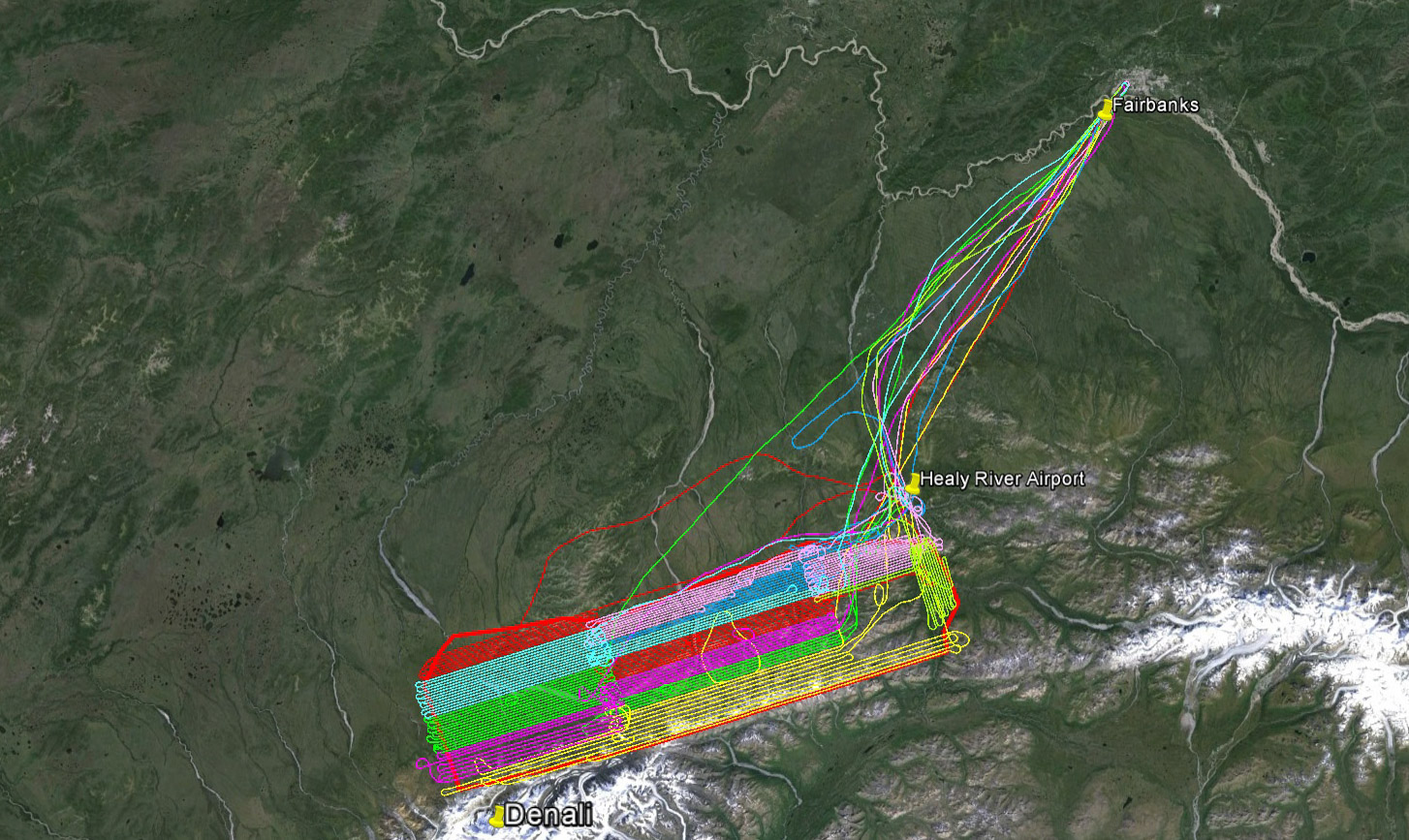

I arranged acquisitions of the area into 5 blocks. The High Block is planned at a higher altitude above ground than the others it has the highest, steepest terrain and I wanted more clearance above that terrain given the notorious potential for turbulence over these mountains. These mountains would be considered large in any other context than here – at 9000’ they are dwarfed by The Big One at over 20,000’. As specified in the contract, the ground resolution here was to be 50 cm, but as planned it averages at 35 cm, with the highest terrain at about 10 cm and bottom of the valleys at 40 cm. Resolution varies with distance above ground, in the same way that it does when a tourist on the ground beneath me takes a picture of their family in front of The Big One – the foreground subjects have a much higher resolution than the mountain because they are closer to the camera. The eastern, middle, and western block boundaries were selected to find a balance between economical flying and the highest resolution. Again, flying at a constant height over terrain of varying height leads to varying resolution, so if I can choose my lines to separate mountains from low lying areas I can then acquire those low lying areas at higher resolution. Balancing this is that the fewer lines there are the less turning I have to do – at about 3 minutes per turn, mapping along these 160 lines will require 8 hours of just turning!

That’s 164 lines totaling over 4500 miles, not including commutes from Fairbanks. The only SfM photogrammetry project larger than this one is my coastal project in southwest Alaska. The area is roughly 85 miles x 25 miles in size.

It’s a sizable hunk of the State.

I arranged the lines parallel to the mountains for several reasons. Primarily it was because of my respect for The Big One – I wanted to spend as little time on its flanks as possible. The mountain is high enough that can catch the jet stream, bringing hellacious winds down to surface level. Regardless of that, even ‘normal’ winds, typically from the south, create eddies as they pass by the peaks of the ‘normal’ mountains. My plane, 21C, is an underpowered single engine piston plane heavily loaded with fuel in the lee side of all that. At altitude I have a climb rate of 100 feet per second, in terrain generating up and down drafts of 1000s of fps, this is really no place to be cocky, and be some would say no place to be at all. But by flying parallel to those flanks, I could choose the best day to fly close to it — if I had arranged the lines the other way, then every day I would have to bump up to it. Not coincidentally, flying in this direction aligns me with the road and its valley, so I can fly a bit lower there.

This is a mountain that packs a lot of punch when it wants to. The trick is figuring out when that is and choosing your battles wisely.

28 May 2016

Today marks the beginning of acquisitions for a massive mapping project at Denali National Park, mapping about 5000 square kilometers or roughly a quarter of the federally owned lands there. I had marked this week on the calendar over winter as a likely start time, figuring it would likely take the better part of June to accomplish, eager to get it done before fire season kicks in and fills the air with smoke.

The forecast was calling for clear skies and light winds from the north, so I prepped the plane yesterday and prepared for an early launch to make the most of what could be a short weather window. Sure enough, at 4 AM the cameras and satellites showed clear skies, so shortly after 5 AM I was airborne and heading south.

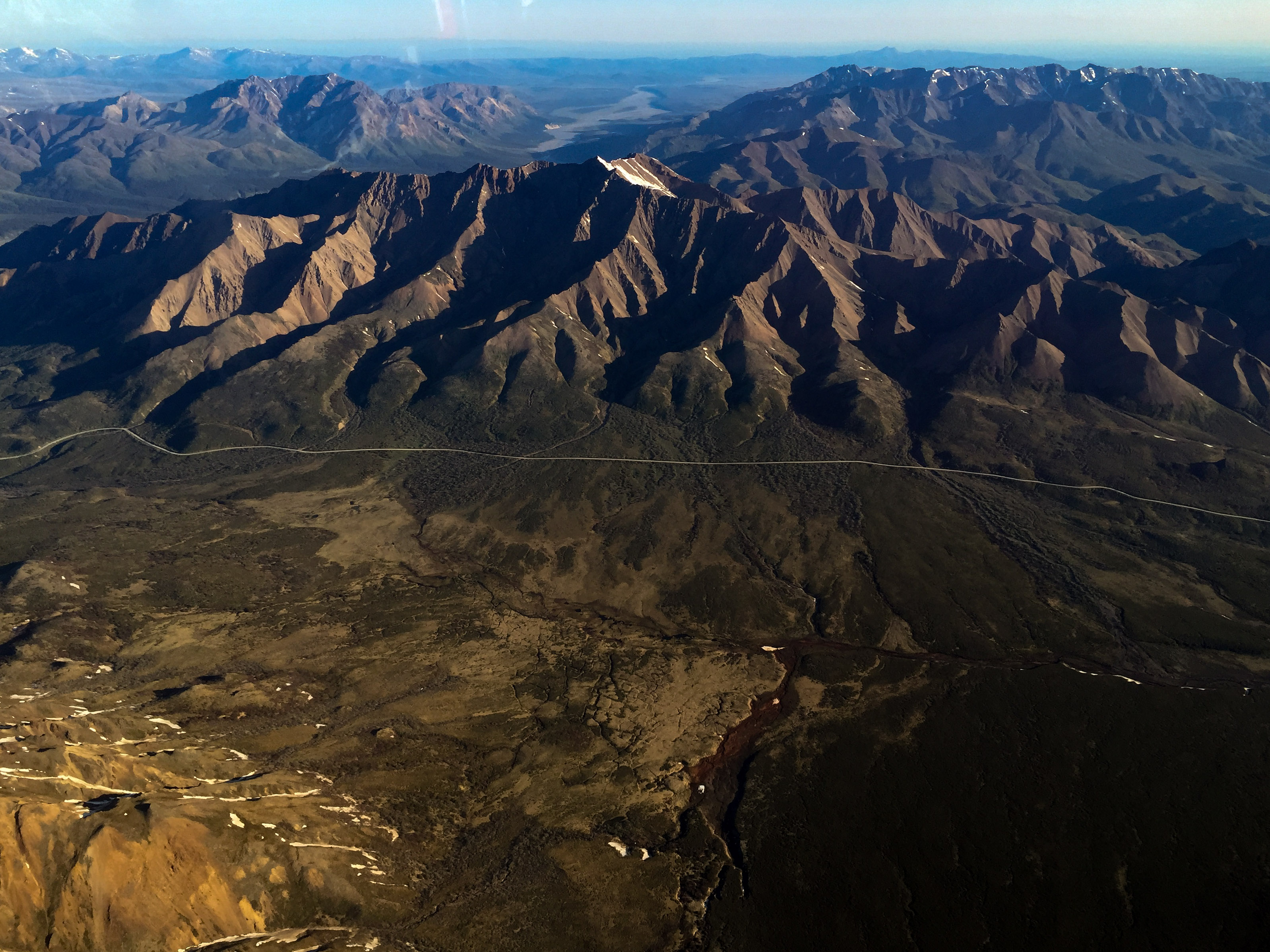

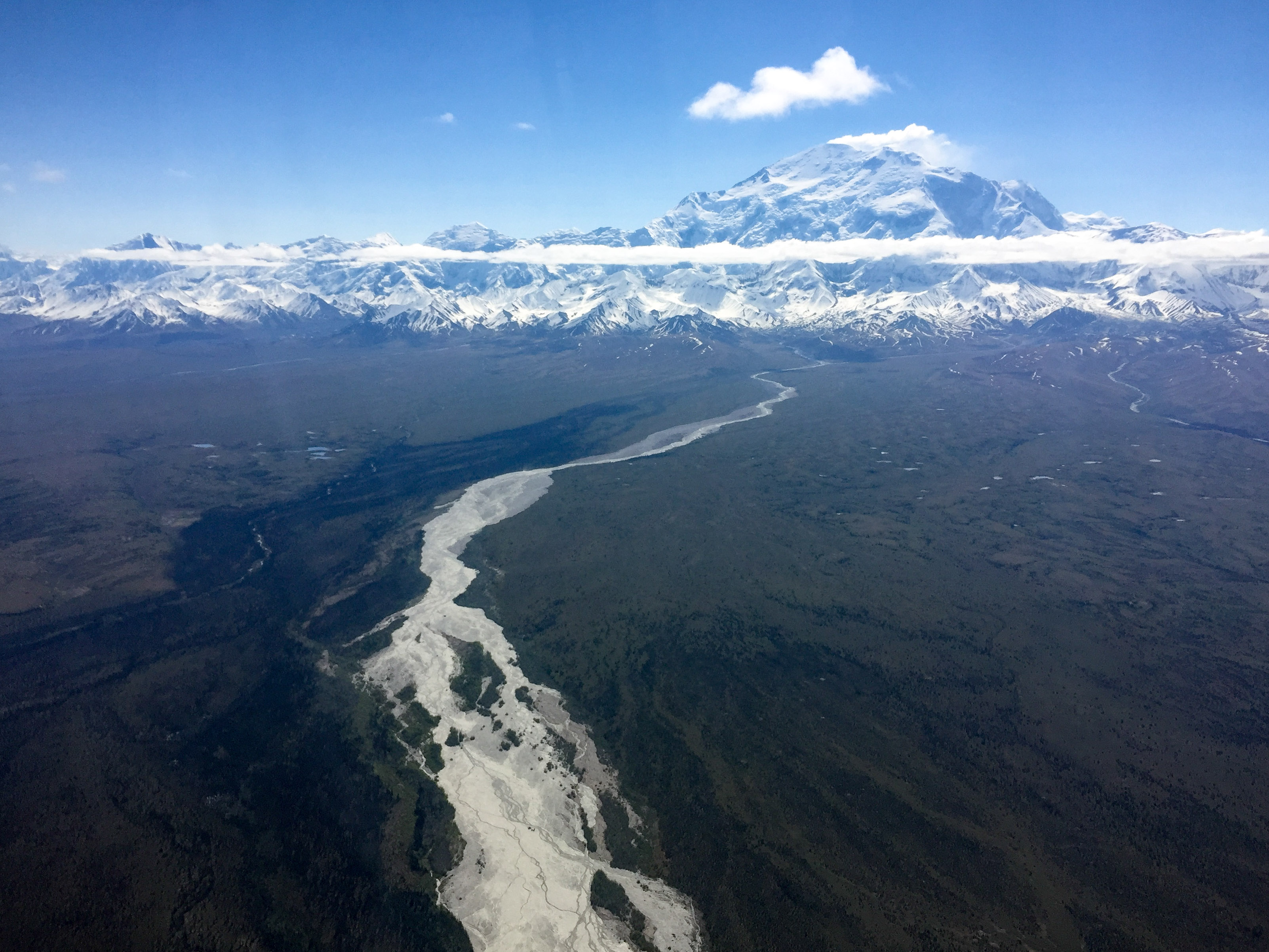

The Alaska Range.

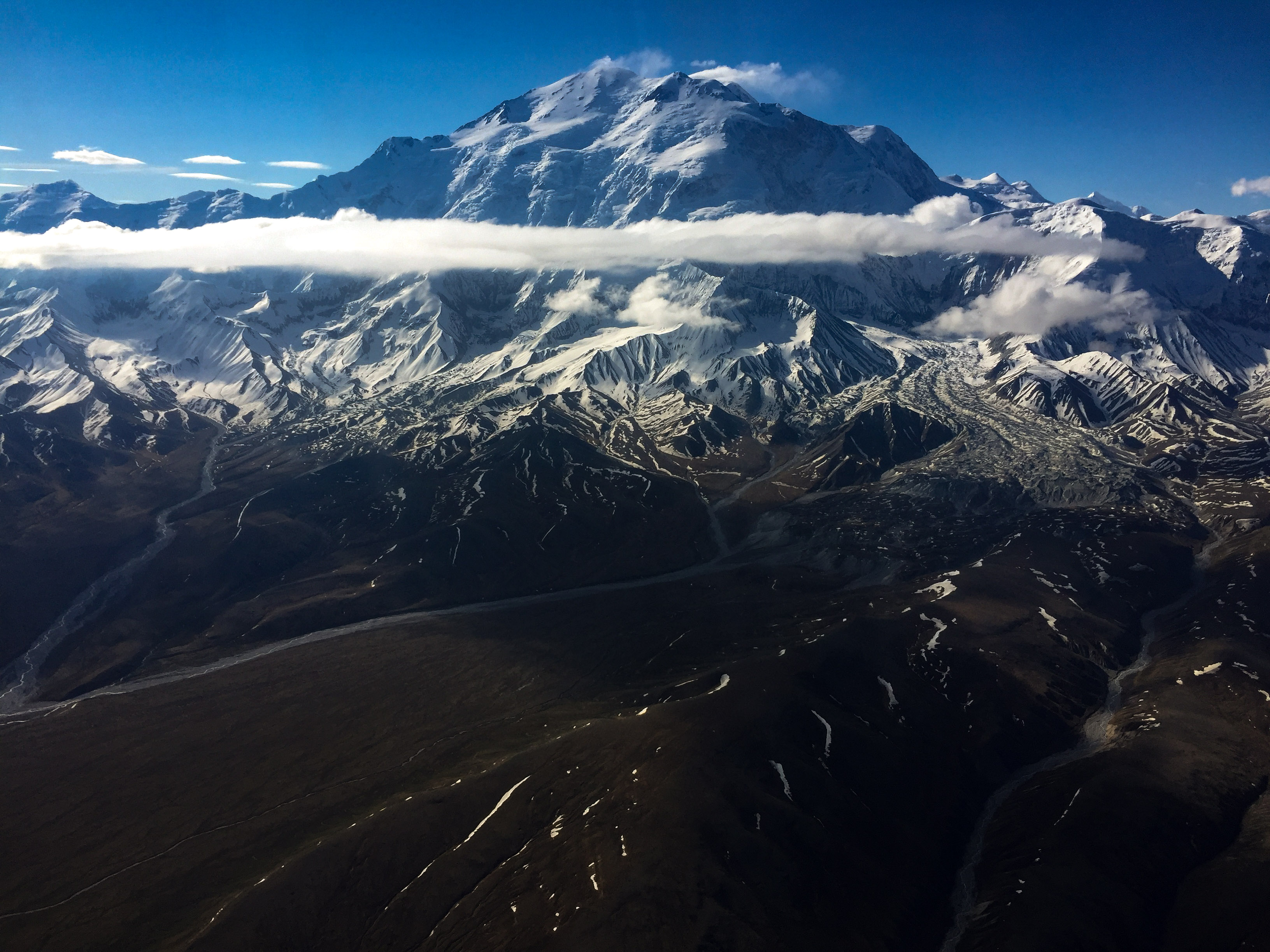

The Big One was an easy landmark to head towards.

The Big One was an easy landmark to head towards.

The weather could not have been more perfect to start this project. The crux of the project in my mind was always the southern boundary of the area which abuts the Big One. Winds ripping around the mountain can cause downdrafts that are preposterously intense, measured in thousands of feet per second. On my lines at 11,000’ along the flanks, in my little underpowered 170 I can barely climb one hundred feet per second. I arrived in the area and tentatively approached the mountain, with a full load struggling to reach 11k. But there was not a cloud in the sky and I was on the upwind side of the terrain, perfect for mapping the high elevations of the project on the flanks of Denali.

The tradeoff here in mapping the mountains versus the low lying areas was the amount of snow cover. The general idea when making a base map is to have it as snow free as possible. Waiting until later in summer would see the snow line rise, but the challenge is that in these mountains it can snow any day of the year and mid- to late- summer weather can be both worse and plagued with forest fire smoke. I had also considered flying these high lines towards the end of the acquisitions to let a little more snow melt, but the forecast at this point was for a week of great weather and I did think a week would make that much difference. This combined with the fact that today might be the only day all summer with clear skies and no wind over the mountains left little choice in my mind. My approach towards acquisitions is always to map the areas with the worst weather as soon as they become available, and this was definitely the area with the worst weather.

The Big One makes all the rest seem small, even at a distance.

The Muldrow Glacier is a surging glacier, and a major landmark on this side of the mountain. You can tell it surges by the loopy moraines, created when a tributary pushes into the main branch during its quiescent phase and then gets beheaded when the main branch surges.

Scott Peak, another pilot landmark on this side.

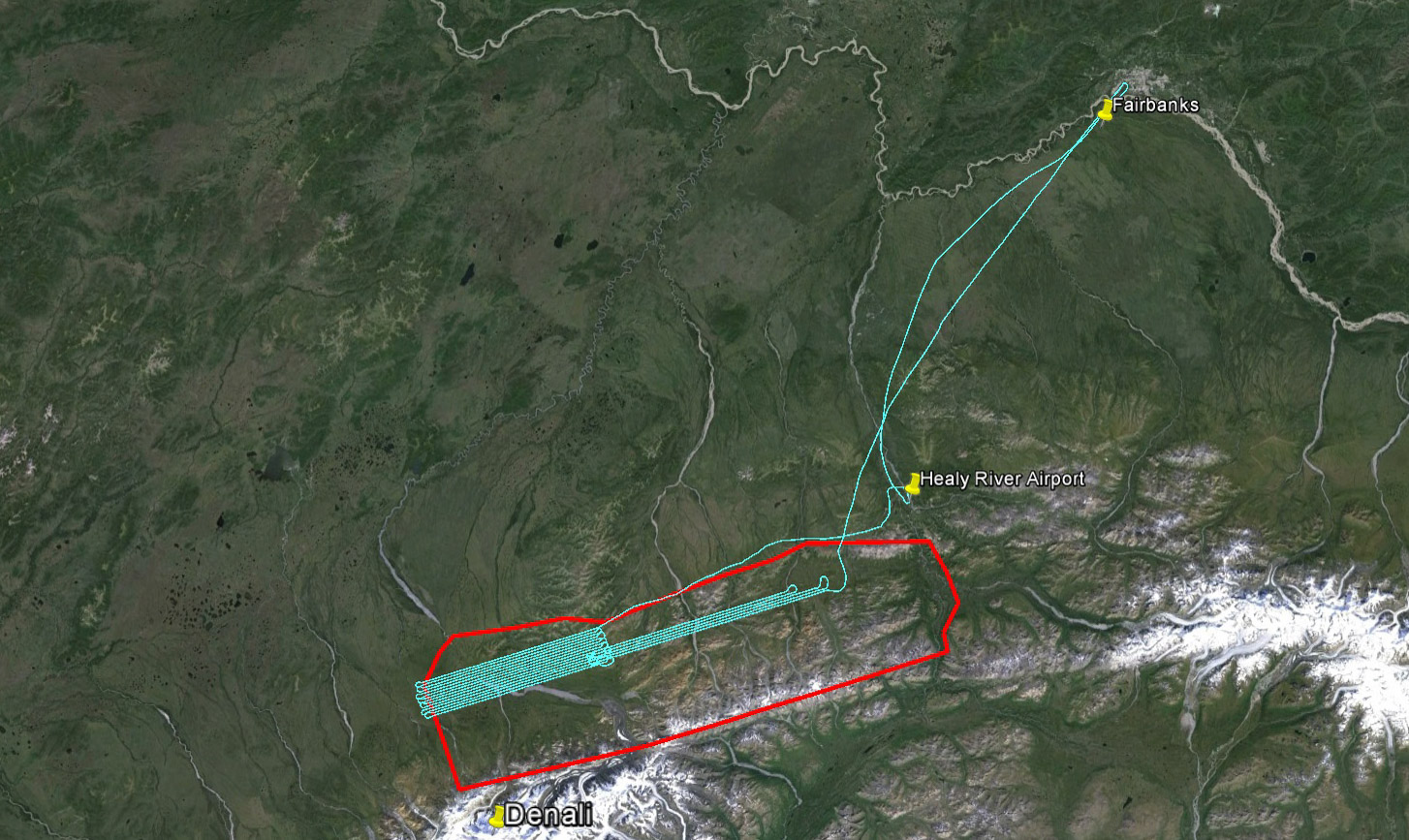

Mapping went well. It took a little less than 6 hours of mapping to get the southern boundary completed. I was more than halfway done by the time the flightseeing tours began, so I wasn’t getting in their hair too much. I focused first on the area around Denali in case the situation changed there and then knocked out the rest. By the time I finished with that thermals and clouds were beginning to form. With the fuel in my wings, I normally plan for about 6 hours of flying with plenty of reserve. But when flying higher in thinner air and leaning the mixture, I can stretch that to 9 hours, though I rarely push things that far. In this case the eastern ends of my lines were directly over my airport, or at least what I thought was my airport. It turns out there were two airports here and the one I was looking at was a private one which looked very pleasant. The public one was smaller and shorter and in a small pit inside a deep valley. When I realized that I decided to head a little further north to Healy, which was just as well since I had to lose a lot of altitude anyway. I carry another 4-5 hours of fuel inside my plane, since the nearest place in over 100 miles to buy fuel is Fairbanks. So after splashing some of that in, I was able to largely work beneath the newly-formed clouds since the high lines were finished. But these were thermally-built clouds, meaning that the air underneath was lifting to create them, and trying lift me with them. Winds had also picked up alongside The Big One. By about 1PM is was simply too rough to continue, so even though I had plenty of fuel I climbed back over the clouds and headed back to Fairbanks to check data, which fortunately all looks great.

The forecast indicates several more days of good weather like this, though likely with the same after noon issues, so it looks like its going to be several days of 4AM wake up and shorter flying times than I would like. But I’ll take a week of those without complaint to finish up in one swell foop!

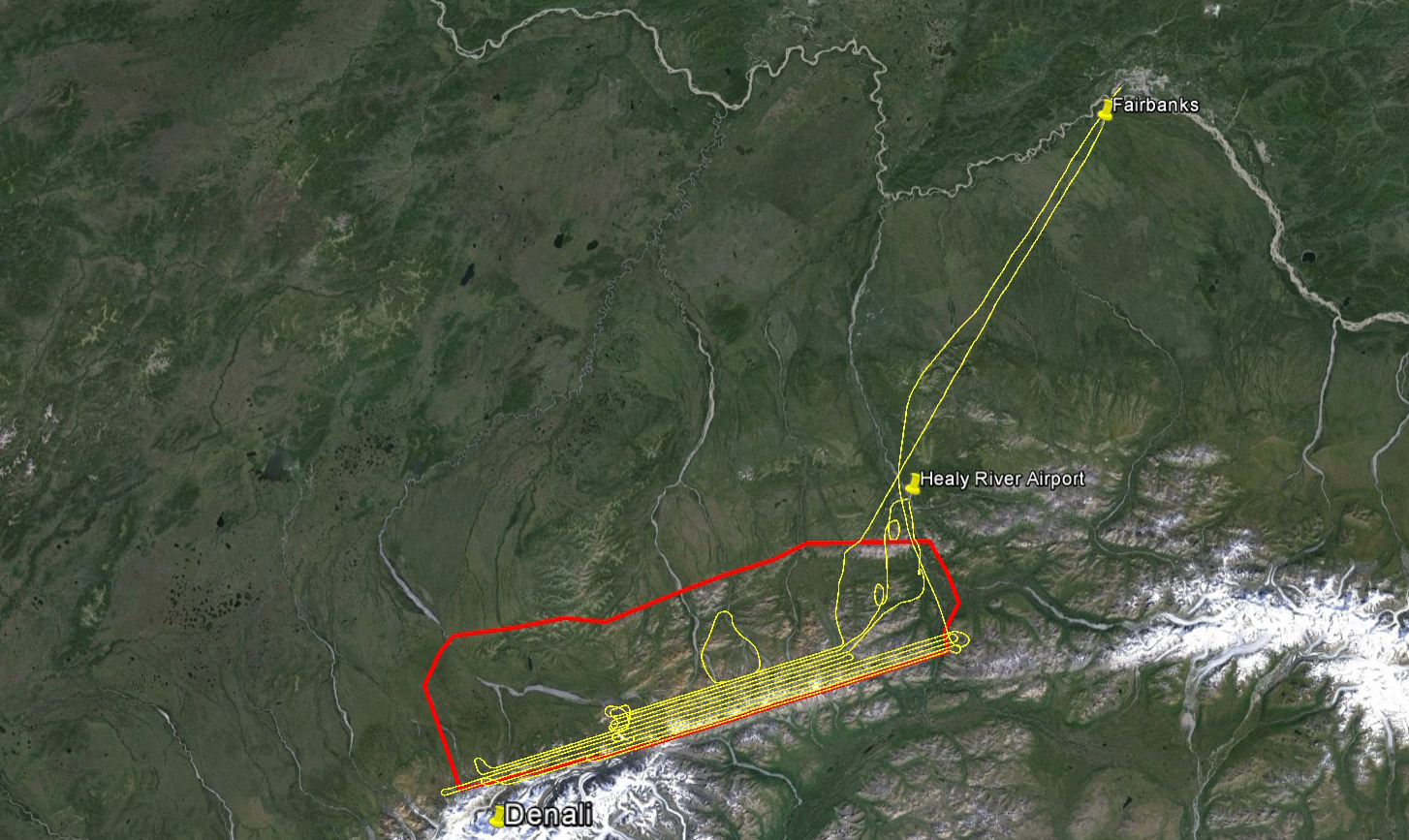

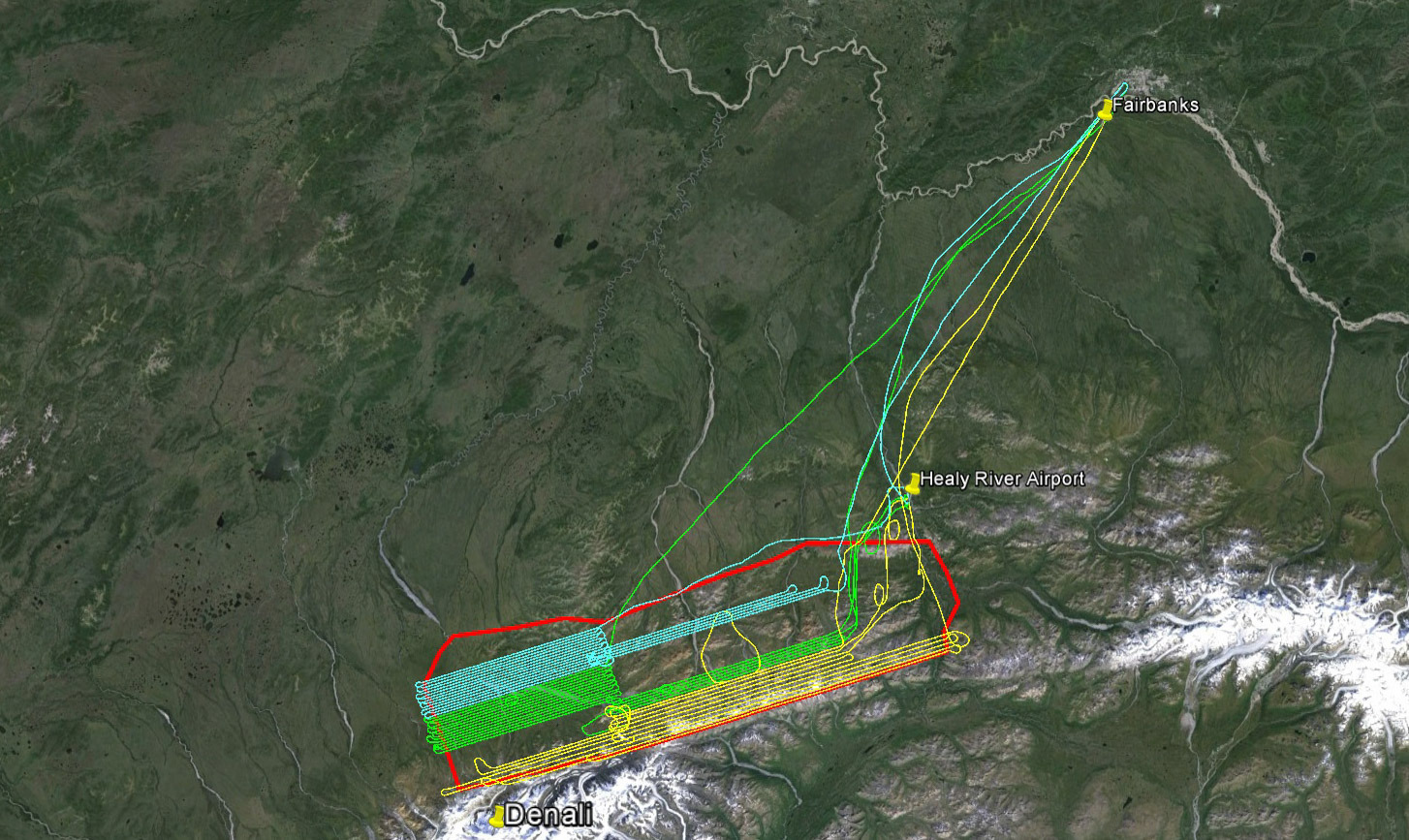

The four lines at right were part of the high block and were completed as planned. I bailed early on the lower pair at left later in the afternoon as I was getting rocked a little too hard for comfort. 21C: 4, The Big One: 2.

Hard to take a bad picture with a view like this. Hard not to take a lot of them either.

The northern wall is a jumble of ice.

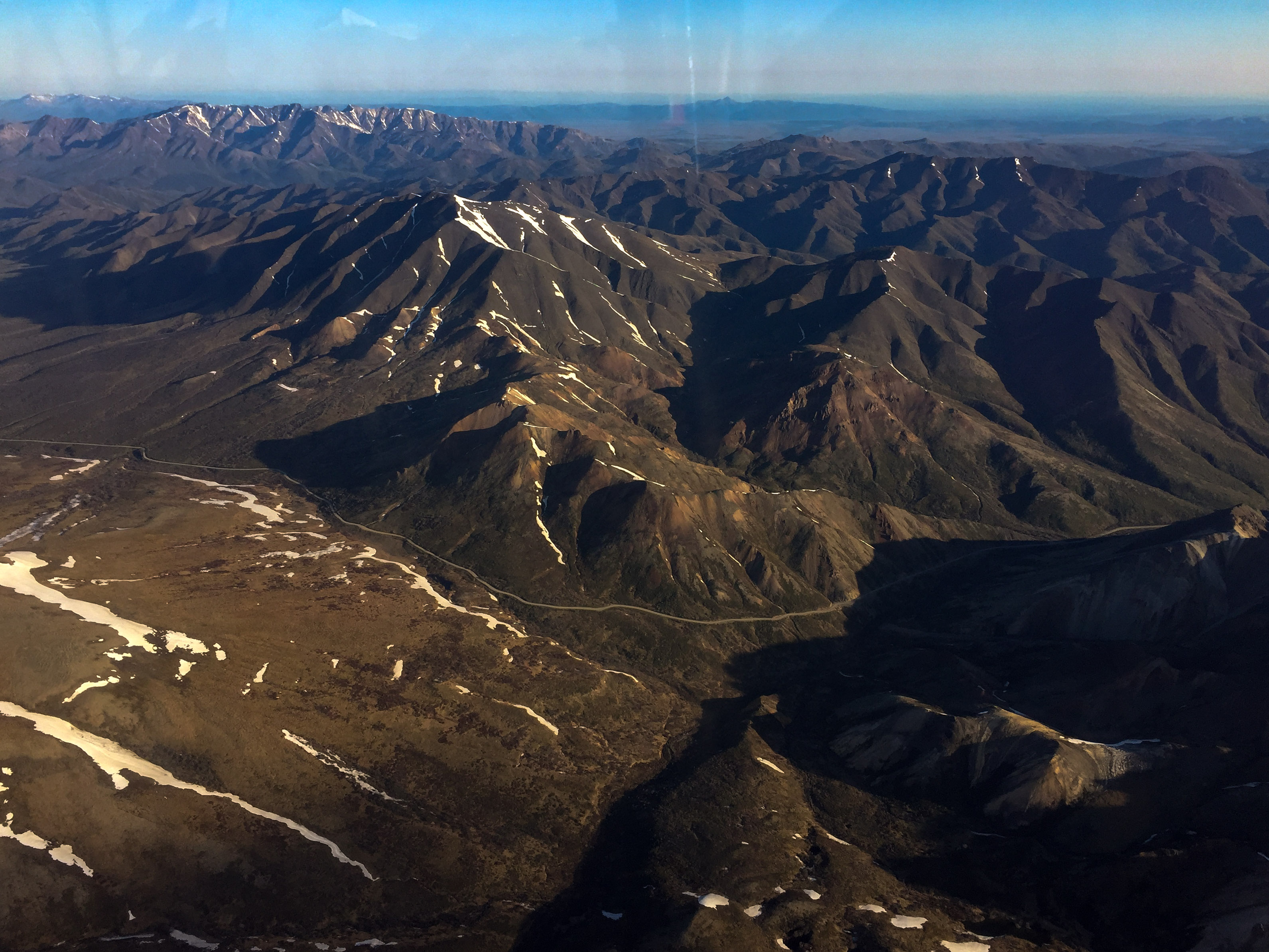

Just some small, insignificant 7000-9000′ mountains nearby…

The bend in the Muldrow, another landmark for pilots.

Not bad for an iPhone shooting through plexiglass and the prop arc.

I passed The Big One six times today.

Each pass brought me a little closer.

This was close enough for me.

Just another day at the office…

By noon the clouds were starting to form, but I had already accomplished my primary objective.

It’s hard to mistake the Healy River airport, even from space.

29 May 2016

Another big day of acquisitions in Denali Park.

With the forecast for clear skies, I was up at 4AM to confirm and airborne at 5. With a strong tailwind and not needing to climb so high, I was soon back trying to pick up where I left off yesterday. The challenge with flying so early is that the low sun angle highlights snow on mountainsides that face the sun and shadows their backs, causing a wide range in exposure values. I had sorted this pretty well yesterday, but because the natural range of values is nearly as large as the camera’s ability to capture, it requires constant checking of exposures to make sure they are in range, which is not always possible given the flying circumstances. But it seemed to work out based on reviewing them back at home. The photographic issue is that by trying to capture the highlights, the shadowed areas are exposed at low end of the bit range. With digital photographs, the information is not distributed evenly, there is more detail captured in the brighter pixels, such that when post-processing dark areas to be brighter, some new information must be created, and that takes the form of noise. Since it is random it does not affect the digital topography made from them in a noticeable way, but the image itself looks a little fuzzier if you know what to look for. But like most things, the art of digital photogrammetry is the art of optimization, and in this case weather, funding, and science are the dominant variables — the goal is to get the project done in two weeks to minimize temporal variations across the map area, and given how much flying there is to do, it cant be done in the two hours per day there seems to be a high sun angle before thermally-driven clouds form.

Fairbanks International Airport, had the skies to myself.

The Big One is just above the horizon near the center of the frame, an easy navigational aid on a day like today.

Early morning sun brightens the snow facing the snow and darkens the shadows on the other side, making for challenging scientific photography.

It was immediately clear that mapping the high elevation part of the area yesterday was a good idea. While it was mostly clear skies, there were a few wispy clouds over the peaks, and more formed as I approached – it would not have been possible to map those lines today without losing coverage to clouds. Plus on top of Denali, large multi-tiered lenticulars had formed, suggesting that the smooth sailing of yesterday was also gone. The charts for winds aloft showed that while the winds were only about 20 mph here, at 21,000’ they were 60+ mph. My goal today was as always to map the area that had the worst weather potential, in this case the southern part of the western block immediately beneath The Big One. You never know until you try, but after the 2nd powerful downdraft I was turning tail and forming Plan B.

As I approached, I could see it was wearing a hat today.

The ‘smaller’ mountains were covered with thin clouds. Good thing I mapped them yesterday.

The ‘smaller’ mountains were covered with thin clouds. Good thing I mapped them yesterday.

As I came alongside the mountain I could see the sombrero wasn’t as friendly looking from this side.

Good thing I wore my brown pants today.

Plan B was to continue the middle block. I had mapped one of these lines on my way to the eastern block, and though there was still a tailwind, it was reasonably calm. The issue was cloud formation over the peaks. I had hoped that I could work my way towards lower elevations more quickly than the clouds, but after about 5 lines I got caught. Had they formed another 500’ higher I could have continued, but they were just above or within my flying height and there was no way to avoid them after a while. Unlike my coastal projects, flying lower here yields diminishing returns due to the extreme topography – the lower I go, the narrower my swaths get and my overlap between lines decreases, potentially to zero. Similarly, flying lower means that ridges and peaks are that much closer to the airplane, which causes issues with the frequency at which I take photographs and the blood flow through my knuckles. I fooled with this a little, but with so much area yet to map it seemed wise to move elsewhere. The eastern block from the morning was still clear and the flight lines there lower, so after refueling I ventured that way again.

Rather than start with the lines closest to the mountain, I stayed at the distance I ended up at from the middle block. This worked reasonably well. There were still some ripples flowing down, but nothing too energetic, and after working several lines progressively further away, it was once again reasonably calm. I spent the rest of the day here, getting quite used to the landmarks. I guess because it is Sunday air traffic in the air was pretty light, so I’m hopeful tomorrow may be even lighter given that it’s a holiday.

Though the day didn’t necessarily go as planned, I still got nearly 7 hours mapping done onsite, and as long as that keeps being the case, I will get it done eventually. I figure I need 6 more days like that, and fortunately the forecast for the next 3 days is still favorable.

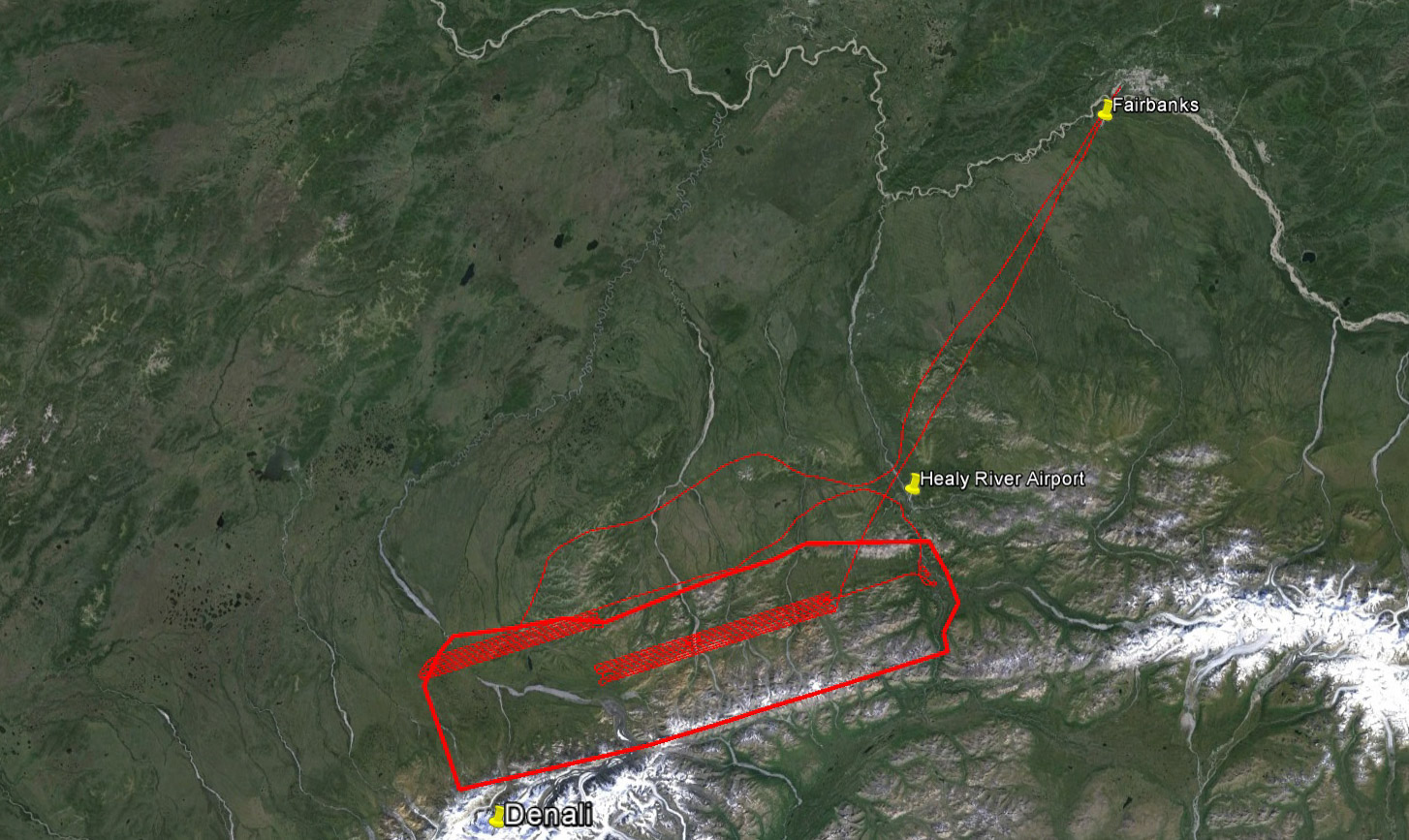

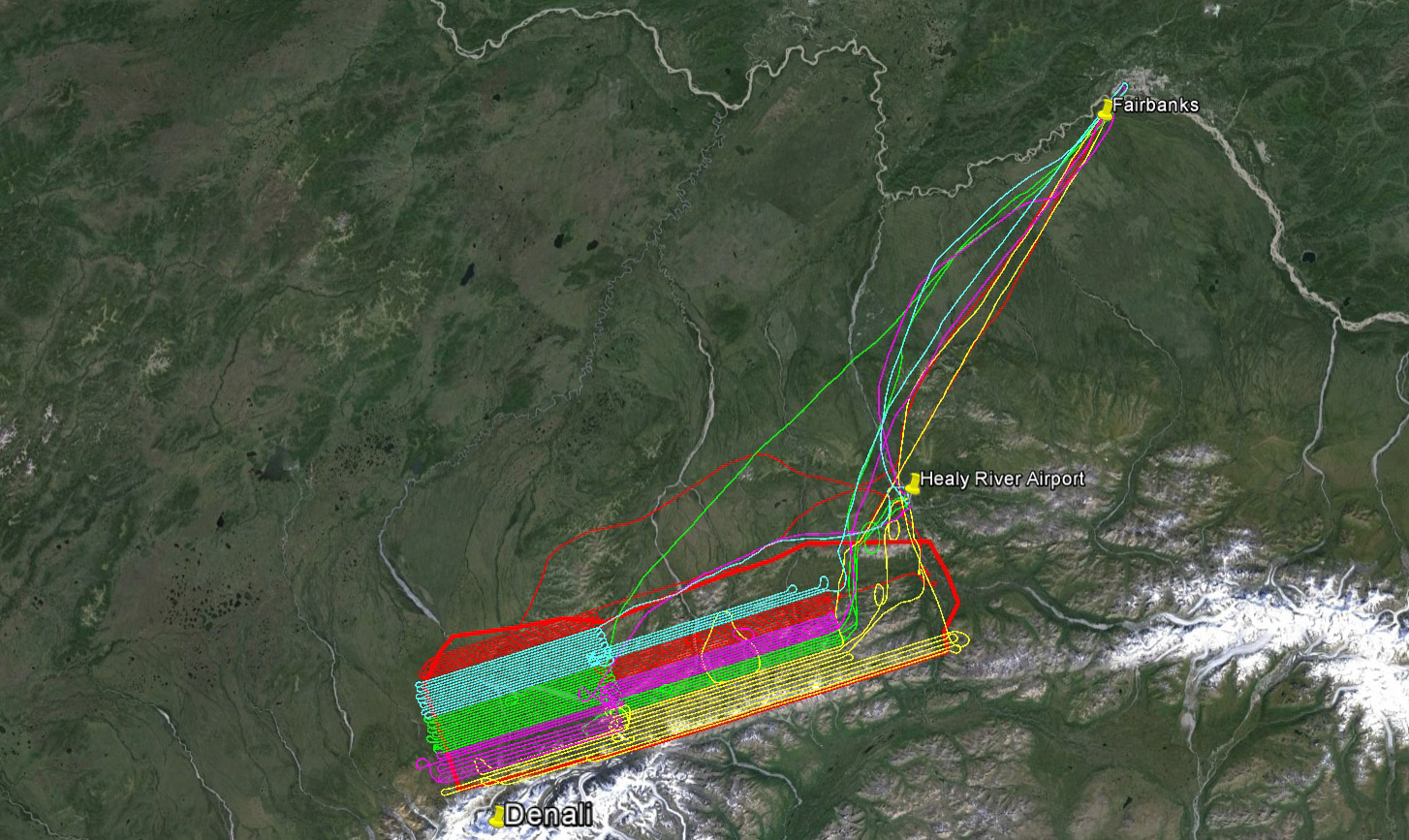

My goal was to pick up lines on the western block where I left off yesterday (yellow) , but I wasnt long into it before I decided this was a losing battle. Later in the day, I picked up further away from the mountain and made good progress. 21C: 14, The Big One: 2.

I kept my distance and mapped the plains north of the mountain.

Much friendlier weather out here. Though those little wispy clouds always spell the beginning of the end of the day.

With so much available area, hopefully I can always find someplace to stay productive, but its going to be harder to pull off as time goes on.

30 May 16

Weather is everything.

I am by now into a regular pattern of up at 4AM and getting airborne by about 5:30AM. The main issue is with thermal cloud build ups. As the sun beats down on the landscape, it lifts out moisture which rises into the air and condenses into clouds. This causes a lot of bumps on its way up and large white things in the sky that cameras cant see through and small planes shouldn’t fly into. Normally this takes some time to occur, in the past few days this time is about 1PM. After this it either too bumpy or too cloudy. But with moist low pressure systems and constant sunshine, it can apparently occur nearly any time. Today I arrived at the area to find Denali obscured by a huge mushroom cloud, which was apparently the remnants of a huge thunderhead from yesterday, and a combination of leftover and newly-forming clouds over the mountains I hoped to work over, so much of the area was already taken out of action. Thus I could not start on the middle block where I left off yesterday, but had to skip a bunch of lines to get to where the clouds hadn’t taken over yet. An overall challenge of a multi-day project like this is to remember which lines have and haven’t been done…

My old stomping ground on the left, behind Mt Shand. I have almost this same view from the roof of my house. Well, before it burned down. But if I finish this map I can afford to rebuild it…

Most of the peaks were obscurred by clouds leftover from the previous day’s convection.

It wasn’t entirely clear within my mapping area either, though I dont have any pictures of it as I didnt dare let go of the yoke.

Compounding this was winds from the south, which sent huge rotors over mountains I was working just north of, creating a continual downdraft along my flight lines, which run parallel to the mountains and apparently exactly where the air is sinking. At this altitude, on a good day I have about a 200 foot per minute climb rate, yet I was continually sinking about 200-300 feet per minute. Even with flaps in and doing a wheelie I could only slow the sink to about 100 fpm. Occasionally during the line I would hit a jolt of lift that would more or less get me back at altitude, but often not. So I tried a few lines by starting high and gradually sinking along the route, using all of my recent glider experience to maximize lift where I could find it. The general idea is to slow down when you hit lift and speed up when you don’t. Unfortunately I was already going about as slow as I could trying to climb and I didn’t dare speed up just to sink faster into the unforgiving terrain. And after a few hours of that, the new buildups were rapidly coalescing. Unfortunately, as it was the for the past two days, this ceiling is right where I need to fly, so I cant go over them or under them. So I moved to greener pastures. Or bluer skies anyway.

It was much nicer mapping weather to the north.

Wonder Lake. I remember taking the long bus ride to Wonder Lake 25 years ago, when we believed it got its name by wondering why the hell we drove ten hours on a bumpy gravel road just to see clouds hiding a big mountain.

By late morning, the cloud surrounding the mountain had disappeared, but the thermals were already building.

Slippery Creek marks the western edge of the study area.

The far west end of the area is pretty flat and relatively low. This has several advantages. First is that wind blowing across it doesn’t create new bumps, which is nice. Second is that because its lower, it takes longer for the moisture evaporating from the ground to reach the altitude where it condenses, so it stays open longer. Third is that because its lower, I can fly lower, such that even when the clouds do form they are above me not in my way. Finally, it just looks friendlier to fly over. So I spent the rest of the day mowing the lawn here, getting about as many lines done as yesterday, such that another 2/3s of a day should clean up that entire block, if I could access it.

Still remaining in this block are the lines closest to Denali. Given my experience in the morning with the middle block, I decided not even to poke my nose into those close lines as it was clear that the descending air was going to be even stronger and nastier on the flanks of that giant mountain. I realized as I was flying that I probably had been a little too optimistic in my flight planning in terms of the division between the ‘high’ and ‘low’ lines. I made that division largely by the height of the mountains, not really taking into account proximity to the mountains and the lee-side the wind and clouds these mountains create. As I flew along today, I considered that it was likely that I may never get another day like the first day, when I could fly anywhere without wind or cloud issues. Since then these mountains have always been topped by at least small clouds even at 6 in the morning and even if they weren’t getting close to them below their peak elevations has been problematic due to wind. So I decided to plan out the higher lines a little further at the two end blocks, rather than fight it out a few lines a day like I’m doing with the middle block. This way I’m above the biggest downdrafts rolling down the flanks of the mountains and even if little clouds are present by shooting down through them with enough overlap I can still get nearly complete coverage, whereas if they are at my level I get nothing. In any case, by noon it was once again it was too bouncy even in the flats to continue working. By now it was clear that it was best to stretch fuel as much as possible by minimizing reserves, as the 1-2 hour delay refueling causes eats into valuable mapping time. So after a splash of gas I was headed for home.

Overall the day went well, with over 6 hours or so onsite of productive mapping. It’s been pretty exhausting, as its about all I can do to prepare for the next day before I need to go to sleep. I’ve flown about 27 hours in the past 3 days, so today I had to change my oil on top of everything else. But if I can keep getting 7 hours a day of mapping done, I cant complain. The challenge is that as I get more area complete, I have fewer choices remaining when it comes to avoiding bad weather, but that’s the nature of the beast.

Though a few hours more would have been nice, cant complain about success.

31 May 2016

The forecast from the night before was accurate and by now I was in a routine of up at 4 and airborne by 5:30. The approach towards the park was encouraging, with The Big One serving as navigational aid.

The goals for today were to try to finish the western and middle blocks. These are the furthest from Fairbanks, and it would seem that the middle one typically has the worst weather, so I want to get them done while the getting is good. Based on my experiences the past few days, I replanned the lines closest to Denali in the western block to be a little higher so as not be caught in the worst of the mountain-induced bumps, or at least giving me a little extra height to play with if I did. Unfortunately there was a thin overcast layer right where I needed to be, probably remnants of the previous day’s thermals. So I began with the middle block.

The sky was largely clear and calm, but there was an annoying thin cloud layer right where I wanted to map.

Weather really is everything. The lines that I skipped yesterday because of the clouds and downdrafts were now as peaceful and pretty as one could hope for. A high overcast to the south I think was keeping the sun off the landscape here and keeping it cool. So soon enough I had a bunch of lines done there and the annoying cloud layer to the west was starting to breakup with the increasingly strong sunshine. Plus the sightseeing guys had woken up by now and I was fine to get back to having a piece of the park to myself, so I moved over the western block to try to connect the pieces there.

It’s a thin ribbon through some rugged landscape.

A small landslide where the road enters the shadows at right closed it in 2014 (I think).

The terminal moraine of Muldrow Glacier, a common aviation landmark. You can see a loop of glacier that got stranded in the last surge towards the upper left of it

Hard to say what the snow line elevation is here. But those drifts are a pain photographically.

The drifts continue to the valley floor, indicating that there’s a lot of wind driven snow here… (this photo is from the next day)

I was able to get up close and personal with The Big One without needing my brown pants, though I hadnt taken them off all week so I was prepared. I climbed up to about 10k and was able to knock the remaining lines without issues. The cloud layer hadn’t fully dissipated but by choosing the lines I was able to avoid it and by the time I was done several hours later it was mostly gone. It felt good to have the western block completed from the mountain to well into the plains, so I’d never have to deal with weather here again – a big milestone for the project.

By now it was 11AM or so. The thermals were starting to build over the middle block and fuel was becoming a concern. By the time I reached Healy River to splash more fuel in, the few puffballs I was planning to fly under on my return had turned into towering cumulus. Similar developments were happening all around, so I tanked up and headed for home. Though I would have liked another couple hours there, it was still felt like a great accomplishment to map what had been unmappable the day before and to stitch together my first large contiguous block – I had passed the halfway mark!

My last lines alongside The Big One. I wont have to be here again until the next map…

The cloud layer never fully disappeared, but it stayed out of my way.

But other clouds were already forming, and soon it was over for the day.

Another productive day.

A big day — passed the halfway point!

1 June 2016

Once again the weather held, now for a miraculous fifth day in a row, and I was eager to stitch the middle block together and get a big chunk of something else done too.

Though the weather was fine, the weather systems were clearly changing once again and the forecast for the next several days was for rain and low ceilings. On approach to the area it appeared that thunderheads of yesterday hadn’t fully dissipated yet as there was a jumble of clouds over the middle block and Denali was completely obscured. There was also a high overcast over much of the area, which I hoped would work well for slowing down thermal buildups.

Weeping Angel wasnt liking the looks of this, but we poked our nose in anyway.

A high overcast actually improves scientific photography as it acts like a diffuser, eliminating shadows and dampening highlights. A low overcast means its time to go home. Fortunately this one was not really in my way.

A high overcast actually improves scientific photography as it acts like a diffuser, eliminating shadows and dampening highlights. A low overcast means its time to go home. Fortunately this one was not really in my way.

I began with the middle block. The thought of having this and western block finished from the mountains to the far foothills was very appealing, so as never to have to deal with the weather in the area again. For whatever reasons this middle block is a weather trap, it seems to have the roughest mountain winds, the earliest buildups, and the cruddiest weather, so getting this out of the way was a big goal. Fortunately the ceilings were high enough here to work, though lowest towards the west where I worked yesterday, with multiple thin layers and precipitation. After a few full lines I decided to work that western side of the middle block to completion by splitting the lines in case the clouds moved in over it. This worked well and once they were done, I finished their other halves, and soon enough I had stitched together another major block. I was now feeling like I had crossed over the last major hump of the project. I was also feeling a little low on fuel, and given the calm conditions I decided to try PAIN.

PAIN is the airport locator acronym for the McKinley Park public strip, and I think probably appropriately named. The airport sits within a deep valley beneath terrain not only on the sides but on the ends too, meaning that if you don’t climb quickly enough when taking off you hit something. Fortunately winds were calm and though the approach is a little intimidating I landed with no damage and tanked up my wings to full. Having spent five days out here and reaching beyond the halfway point, I was more inclined to try to slog it out with whatever pieces of lines I could get. I had initially planned to be flying 10-11 hour days out here, but rather was flying only 6-8, so I had already lost at least a day. In any case, I was hoping to get to the point where I could finish the project in just two day trips, so that I could make use of shorter weather windows. So after fueling and chatting a bit with one of the local pilots, I headed off to see whether the clouds were going to give me a break or not.

Splitting the lines makes for more turns, but it’s worth it to get the job done. Reminds me of granny knots.

It was a nice calm day on the ground, as shown by the wind sock. If you look to the left of the sock, you can see the FAA weather cameras on a tower.

Taking off to the north spits you out into a narrow canyon. To the south you have to immediately climb over a small mountain.

I cruised around Usibelli Coal Mine for a while, hoping a gust of wind would clear out the clouds without taking me to Prudhoe.

Had I waited another hour or two, the clouds might have finished letting loose. But it’s tough enough to get to bed by 8 as it is.

Time to find somewhere else to map.

By the time I made it back to the middle block, the clouds were dumping rain, so there was no chance there. I skirted by those to see what I could do to finish the western block. This corner of the study area consistently had the best weather, and indeed the plains that extended another 50 miles to the north were always sunny – made me wish that was the study area! I was saving this corner for a rainy day when nothing else was available, and I guess this turned out to be that day. It wasn’t the smoothest ride, especially near the middle block, but it was workable and out of the way of the flightseers working their way through the clouds where I had finished up that morning. Eventually though it was simply getting too rough even in this area and the middle block’s storms began expanding in this direction, so about halfway on my last full line I bailed and headed home. But now we were well beyond the halfway mark and into the day trip range for finishing up. Though I’m ready to leave in the morning, I’m praying the forecast for bad weather is accurate, as I could use an easy day…

No PAIN no gain.

No PAIN no gain.

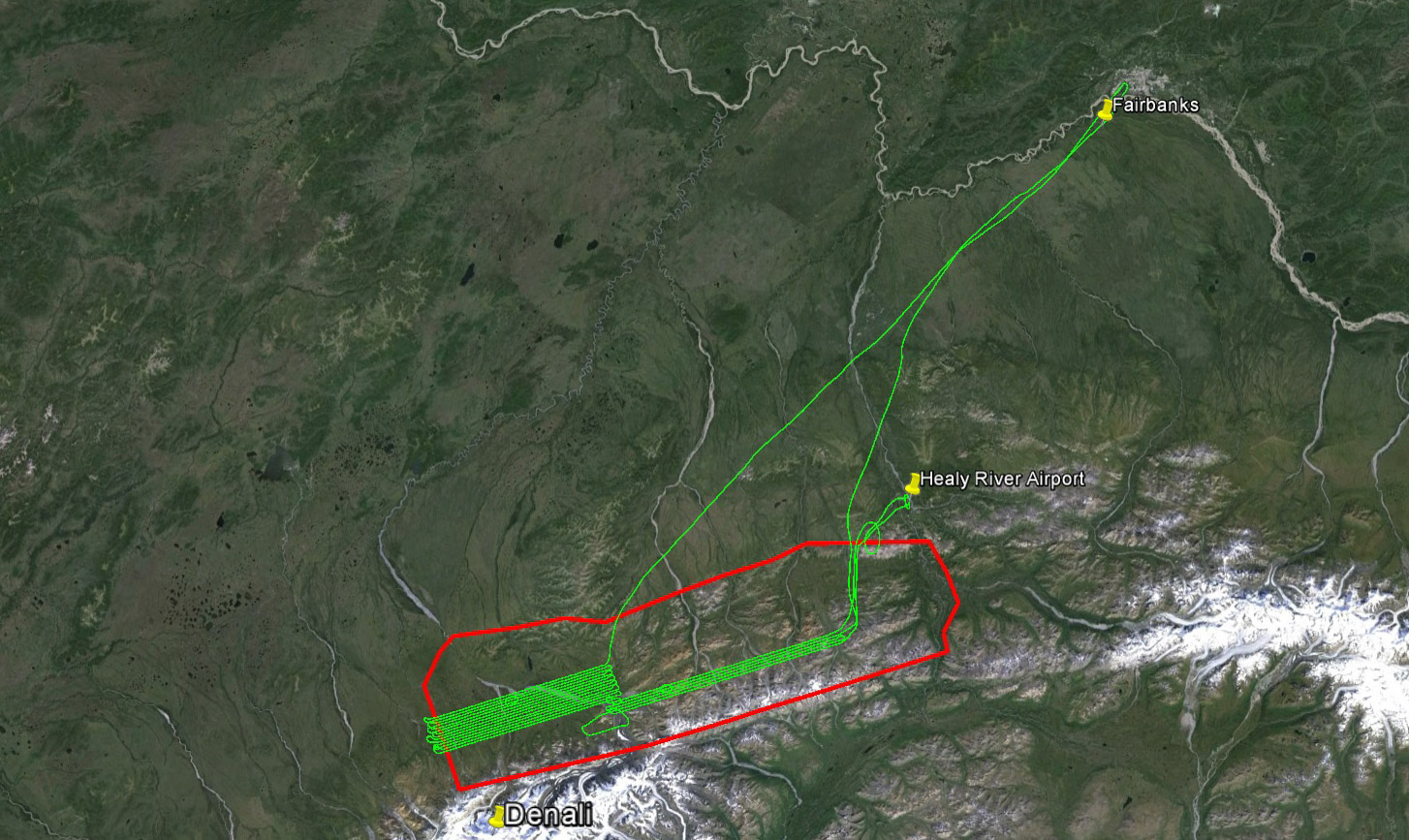

A great day — finished the western block and all acquired data are now contiguous!

Overall: 21C: 54, The Big One: 4

Ugh. I may be winning the war, but the battles are taking their toll…

2-3 June 2016

Bad weather, sleep, data processing, sleep, bad weather…

4 June 2016

The good weather of last week couldn’t last forever, which was just as well, as it was nice to get some rest and catch up on things. I had flown about 45 hours in those five days, so it was also time for an oil change, among other things. The weather this morning seemed encouraging, so was airborne by 5:30AM again and ready for a productive day.

Everything seemed encouraging at first. The eastern block was covered by a low overcast, but the approach to the park was all sunshine. My hope was to map the remaining high lines over the mountains of the eastern block, but these had low clouds nestled around their peaks, so my goal became finishing the middle block. All went well with the first set of lines. A tiny, wispy puffball had formed near the middle of it and above, which I didn’t think much about. But by the time I turned around for the next set of lines, it had grown substantially vertically and was beginning to be intersected by a thin layer at my elevation. I was able to dodge it at first, but soon it was enormous and expanding. I had to end the next lines early, the next line earlier yet, and I barely got started on the next pair before it chased me out of there completely. By 9AM I had been chased out of there!

I moved over to start the western block on the northern side of the mountains which seemed to be containing most of the clouds to the south, but before long I had run out of mappable area. I decided to take a break at Healy River to see whether conditions might improve, but even as I fueled I could see that the vertical development was becoming enormous. I chatted for a while with the flightseeing pilots and checked out their turbine Beavers, wondering what life would be like with that much power in front of me. I loitered for a while after taking off and poked my nose around towards the eastern block to see if I could finish up those lines, but it soon became clear that I was done for the day.

A high overcast covered much of the area.

The mountains were covered in clouds, so no chance of doing them today.

The mountains were covered in clouds, so no chance of doing them today.

Not great here either.

High overcats are fine, though transitioning in and out them is a photographic pain.

I was able to get some mapping done here, but not for long.

That cloud over the Weeping Angel’s head wasnt there at all 30 minutes ago. Soon it shut me down and kept chasing me.

The same was going on everywhere — these little puffballs were forming and turning into towering cumulus in minutes, and it was only 8AM!

I moved outside of the bowl and mapped here for a while.

I landed at Healy River to refuel and give the clouds a chance to gracefully depart my study area, but they called my bluff.

By the time I launched, it was all over.

This little valley is a nice place to circle and think about options.

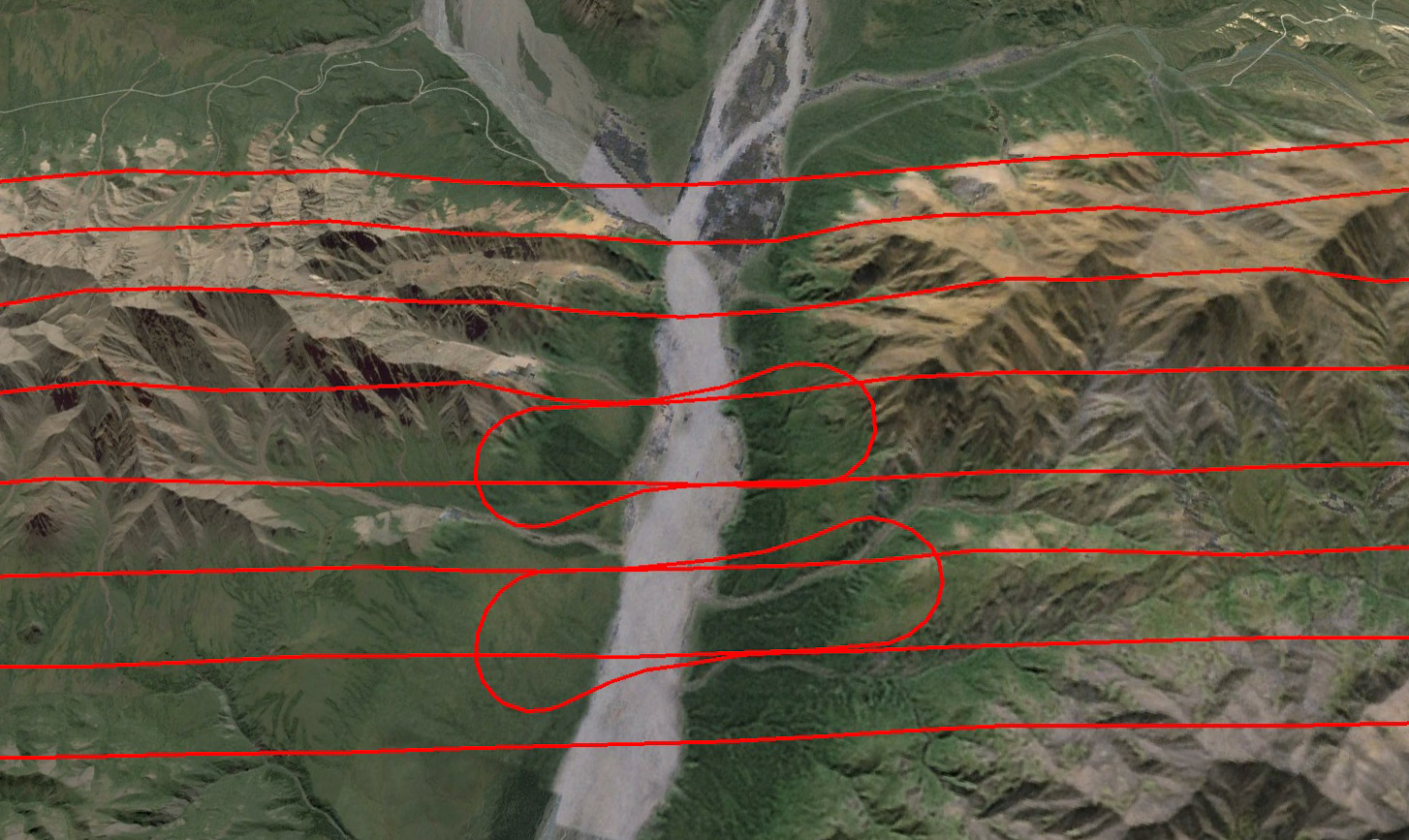

Somewhat disappointing, but a few hours is better than nothing. All of the blue lines should have reached as far as the lower set, but cloud formation turned me around earlier and earlier on each line.

10 June 2016

After nearly a week of crappy weather, I was encouraged by the forecast last night and even more so by the weather cameras this morning. By now I was starting to get used to be up at 4AM and not flying, as I could get a whole day of work in before lunch. But I was also eager to finish the project, so I headed off.

The approach south was encouraging, but became less so as I made my way to the middle block to try to finish it off. Many of my lines had been stopped short the previous week by the sudden early morning buildups. Now there was a weird low overcast in place, probably leftover from thunderstorms yesterday. I started on a fresh line a bit north of the others as it looks clearest there and I wasn’t yet sure how the winds from the south would rock me over the more mountainous part. But things were reasonably smooth, or at least not scary, so I began working in towards the half-finished lines. Trying to cleanup lines like these is a mental chore, at least in terms of being efficient, as you don’t want to end up on the wrong side of the block with nothing left to map except half lines on the other side of the block, forcing a commute. Compounding that was that the clouds were moving, so I was also trying to pick the line that had the best opportunity to get all the way through. In any case, this went well enough and soon I had finished the entire block (!) and was ready for some fuel and relief.

From a distance it looked fine.

Closer up it was more of a challenge, but workable.

The weather continued to hold out after I relaunched. This was the first day that I had not seen significant thermal cloud development. In fact the last bit of high mountains was still in the clear at noon. It was extremely tempting to go map them, but by now the winds had picked up from the south and though there were no buildups, the air was increasingly unstable, so I chickened out and began the filling out the eastern block from the north side. Here there are still some tall mountains, but there is just a thin line of them giving me options on either side. As anticipated, it was mostly a white knuckle affair, but after a week of not flying and the opportunity of having a ceiling and fuel, it was worth it and really only bad over the highest peaks. Soon enough I was back into the lowlands and had mapped far enough south that I covered the park road, meaning that I had now mapped the entire road, which was another welcome accomplishment.

Today’s lines in pink, last week’s in blue. Picking up partially flown lines is a mental challenge. Fortunately I’m a bit mental, or so I’ve been told…

After returning home I checked the data and prepared for tomorrow. As planned, I only have about 8-9 hours of flying left – I could finish this up in one perfect day! Or it could take two weeks of occasional 2 hour windows. If not for the first week of great weather, this project could have turned into a disaster. Knowing what I know now of the weather there, it was incredibly optimistic to think that I could map this area in two weeks, as even on the best weather days the thermal buildups cut short the mapping day by several hours—if not for those, I would have been done already. Given the size of these mountains and their location in the transitional zone between southern and interior weather, this could well be the worst area to map in mainland Alaska.

I forgot to take the picture I wanted to take here, but these guys were trying to fill their Navajo using an old Coyote Air fuel truck on the other side of the plane, but couldnt figure it out. I was done fueling my plane with my hokey system before they could call for help.

Turbine Beaver on wheel skis. These guys make landings on the south side for tourists, about $500/person.

Always less than I would have liked, but still significant progress nonetheless.

Always less than I would have liked, but still significant progress nonetheless.

11 June 2016

With only one full day of acquisitions remaining, I was looking forward to completing the project today, but it was not to be.

The forecast was for clear skies, but at 4AM the cameras showed clouds throughout the park. As I approached from the north, a huge sweeping frontal cloud covered the Alaska Range and dipped down over the road where I wanted to go. I skirted it and descended a bit, hoping that it was just a narrow squall line. Fortunately it was, and though the weather over the park was much better, it still wasn’t enough.

A fuzz covered the entrance to the pass.

On the other side it was better, but not great.

I began by picking up the lines from yesterday in the eastern block. Here the ceiling rose up and down, just barely high enough over my first line. Worse, the winds from the south were creating a downdraft parallel with my route over much of it, so I was fighting to keep altitude most of the way. As I made my return line back towards the road, I was now much closer to the cloud front to the south, which was too low for my lines, plus the bumps were much bigger. I decided to begin mapping the final block over the road corridor and hope that conditions improved over the Park.

Weeping Angel: “Abandon all hope ye who enter here”. I never argue with a lady.

Within the valley that the road goes through, the winds from the south seemed to increase, giving me a +/- 20 knot head or tailwind. It was reasonably smooth over most of it, but on the southern end at Windy Pass, the clouds had lowered and the air got considerably rougher, so I wasn’t able to map the last mile or so of the lines. Fortunately I had planned the lines from the high block and the eastern block to overlap here in case of exactly that issue, so we didn’t lose any coverage, just a bit of resolution as these road lines were lower because they nestled into the lower terrain.

By the time I finished with the road block it was about 9AM. Air traffic was starting to increase and the clouds over the park were looking worse instead of better. So I thought I would clean up the few lines on the northern boundaries I hadn’t got to yet as it still looked open there. I went north down the road and cut west behind the large mountains on the north edge of the eastern block. It was pretty smooth sailing, until suddenly it was not. Within seconds my smooth air turned into the worst turbulence of the trip so far. I got rocked by alternative 1000+ fps up and downdrafts, causing airplane contents to go airborne and the pilot to reconsider not taking a parachute. I turned back the way I came and before long crossed back into the smoother air. I had the impression that this was more than just the normal bumps associated with the lee side of mountains, but rather that the mountain boundary layer was dipping down right into those mountains , which were the last major foothills on the north side, as some front was pushing through from the south. Clouds nearby definitely had the appearance of droopy layer cakes, and not very friendly looking. So I took that as a sign that it was time to head home.

This may not look like much, but about halfway through that turn to the left I got trounced. Where’s that Beaver when I needed it?

This may not look like much, but about halfway through that turn to the left I got trounced. Where’s that Beaver when I needed it?

Not the highest priority work, but it all has to get done.

I’m starting to run out of colors — time to wrap this up!

I’m starting to run out of colors — time to wrap this up!

One of the things that had been bugging me these past two weeks was that image quality was not as great as I am used to. Part of it simply had to do with the issues associated with capturing the full dynamic range, so for a lot of photos I’m brightening dark images which adds a bit of noise. But something else was nagging me about them, which probably no one else would notice. I tried refocusing the lens several times over the past 10 days, which didn’t help, as it was clearly focused correctly. I replaced the glass covering the camera port with a piece I had removed a year earlier, thinking maybe I had scratched it microscopically by cleaning it too aggressively, but that didn’t help. I replaced the glass with a brand new piece and that didn’t help. Given the early end to acquisitions today, I decided to dig into this further so I set up a tripod and laptop tether so that I could shoot and study image quality under more controlled conditions. I tested the lens on a different body, thinking perhaps years of being rattled had loosened something inside it, but it more or less looked fine on both bodies. I removed and replaced the lens a bunch of times thinking the connector ring had worn out, but nothing. I ran it through different aperture and exposure settings, but couldnt find anything. I tried different focus methods and settings and still nothing. I tried a different lens to see if the body itself had an issue, but nothing. It was a bit discouraging not finding something, until I started packing up. It was at that moment I realized I had been using the wrong lens the entire project! A few weeks ago I let myself get roped into a small project testing a different camera body, and I put my favorite lens on it, putting my backup lens on my body. When that small project ended, I didn’t replace the backup lens, and never thought of it again as that’s the first time that lens has been off that body in years, so its just not something on my checklist. I’ve done rigorous comparisons with those lenses and both give statistically identical topographic measurements, but image quality is a nit higher with my favorite. The backup is also little longer, so yields higher resolution for a given flying height, at the sacrifice of width, meaning lines should be flown closer together. Because I flew the lines wider as planned for the shorter lens, I had a moment of panic thinking I would have to refly the entire project due to insufficient overlap, but running the numbers showed that when flying at the planned height, it only reduces overlap a few percent, not enough to worry about. And as it turns out, being the chicken that I am, I almost always flew higher than planned and that resulted getting back to the planned overlap and a net benefit to the project in getting 10% higher resolution data. So mystery solved and project benefited. With everything setup, I took the opportunity to repeat a bunch of image quality testing I had done years ago when developing the system just to reconfirm I’m not missing anything, and now several hours later I’m once again scrambling to get to bed to be ready for a 4AM wakeup…

12 June 2016

I woke up at 3 this morning to discover fog and rain was covering the interior of the state with the forecast for widespread thunderstorms like we had yesterday. Rather than roll over, I decided to get this blog online and get my plans together for mapping elsewhere so that I can dive right into that once I finish the Park acquisitions.

Thus far I think the project has been a success. Through a combination of luck, planning and cowardice, I’d say the battle between 21C and The Big One has been in my favor thus far — I no longer have to get within 25 miles of it and I only have about 6 hours of mission flying remaining. Had I finished that first week, I would have declared myself the big winner, but we’ve now passed the two week mark for acquisitions and some challenging acquisitions still remain. To succeed there will take a day with perfect weather, and with everything else complete it is now a waiting game as I have no alternative areas to map. I’ve had 8 mapping days thus far. If I could have mapped only 30 minutes longer each day, I would be done by now, but I feel like I pushed things as far as I should have and I made it home each night, so I’m pretty happy with progress. The forecast for the next days is mixed and changing throughout the day, so it’s just a waiting game at this point to see how the final battle between 21C and the The Big One will unfold.