Slogging the Sag

I returned today from a short but intense trip to the Arctic, flying 25 out of 52 hours to acquire 22,000 photos, mapping about 100 miles of the Dalton Highway and Sagavanirktok River near Prudhoe Bay, covering about 800 square kilometers at 10 cm resolution, to support a study by UAF and DOT of how extracting gravel from the river for roadbed materials affects floodplain geomorphology.

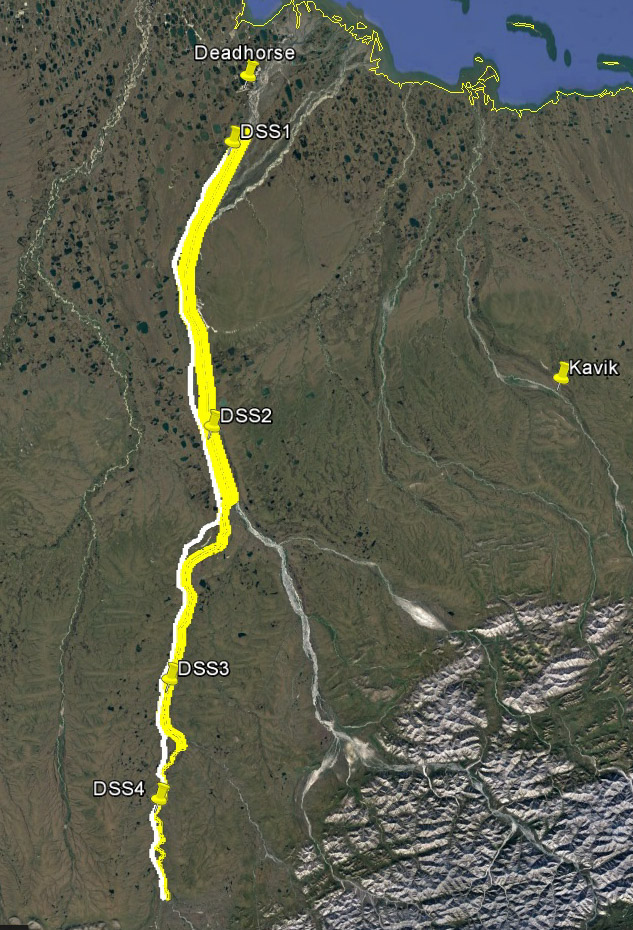

I dont know the full scope of the science involved, but the basic idea is to understand the impacts of earthworks on the geomorphology and ecology of the Sag River. The map we are making now is largely a base map to understand the current river floodplain and road so that future changes can be assessed. The study area covers the same area that I mapped last month to understand aufeis dynamics impacting the road, but is much larger. Within the study area are at least four gravel extraction sites where controlled experiments are going on, with the basic idea that repeat mapping here will directly measure how the river responds to those activities. While important here in its own right, gravel extraction for road construction and mining occurs in rivers all across Alaska, so it is hoped that what is learned here can inform best practices elsewhere as well.

The field work for this project began last summer but the mapping project portion was not funded until early September. Because the science involves assessing change to the ground surface, having the area snow-free was an important acquisition parameter. I flew up the day the project was funded, but unfortunately due to early snows in August which had not melted, it was simply too white to map and thus got orphaned. So there was a certain eagerness to get it acquired as early as possible this year, but also have it snow and ice free. There was also a scientific need to acquire the data without temporal gaps, so as to capture a snapshot of the river’s state without changes in water level or sediment redistribution. So many acquisition plans were created to meet the challenging and ever-changing environmental conditions over the course of the project, but finally the time had come to move forward and get’er done.

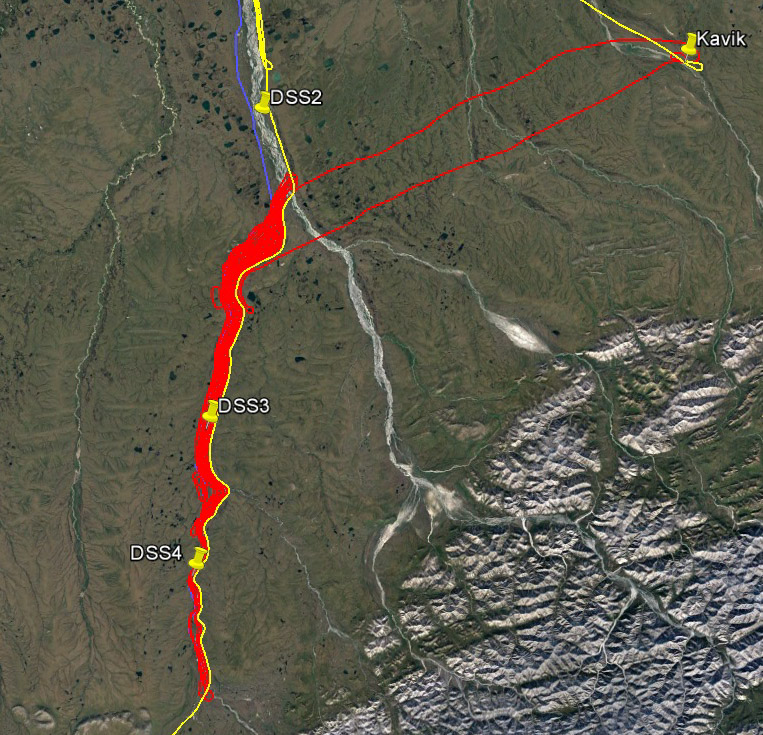

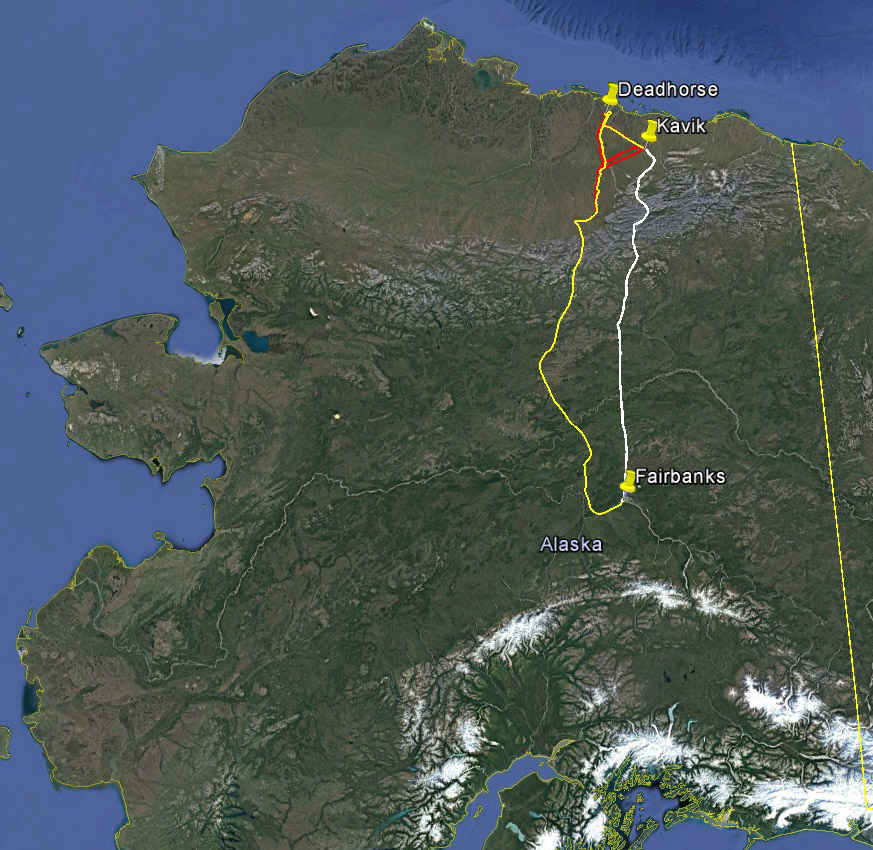

This was one iteration of the acquisition plan, which followed the river and road separately. The final idea was to do this, but fill in as many gaps between the river and road as possible. There are four field sites associated with the study, indicated by the waypoints.

Being nearly 400 miles away, crossing a major mountain range and four climate zones, meant that weather was the biggest obstacle to acquisitions, as usual. So my plan was to base in Kavik for a week and wait there for appropriate weather windows. I had two other projects lined up nearby as well, such that I could head in whichever direction the weather was good — another coastal project near Kaktovik and mapping the glaciers near Peters Lake. My hope was to map the glaciers on the way up there since I had to cross the mountains anyway. As things worked out, until Tuesday the weather somewhere en route was too crappy to make the trip, but forecasts showed several days of great weather starting then. So I was up 4AM Tuesday morning hoping for a productive day. Though weather was great to the north, weather in Fairbanks was marginal at best. I took my time loading up hoping things would improve but it was pretty unsettled. I’m not opposed to fighting my way back home when needed, but taking off into marginal conditions is not my thing. It looked like it was lifting, so at 6:30 I started up and taxied towards the runway, but I chickened out and decided to give it another 15 minutes. It soon went IFR. After a three and half hour nap in the plane, it finally lifted and I took off.

This was the first 3.5 hours of my trip, waiting for the local weather to improve.

A major annoyance and flight planning issue in the interior are afternoon thunderstorms. These start building up by 10 or 11, so I always try to get an early start to avoid them. Unfortunately now I was launching at 10AM and had to fly an hour out of my way to avoid just regular bad weather, so not only did I have to write off mapping glaciers this morning but I began to have serious concerns whether I would make it across the mountains in time. Once headed north I kept climbing as high as my little plane would go and by the time I hit Coldfoot was up over 11,000 feet, working my around build ups rising much higher than me. I bumped into Dirk on the radio who was frenetically shuttling people around the Arctic to flush out the backlog of the past few days of bad weather, and was glad to hear he was still trying to get my load of gear into McCall Glacier to support a trip there later this summer. Fortunately further north over the mountains, the buildups were less frequent and soon enough I was dropping down on the north side.

Weeping angel wasn’t really liking this.

Closer to the north side they werent building up so high and were more scattered.

Once over the divide it was blue skies, but rough air.

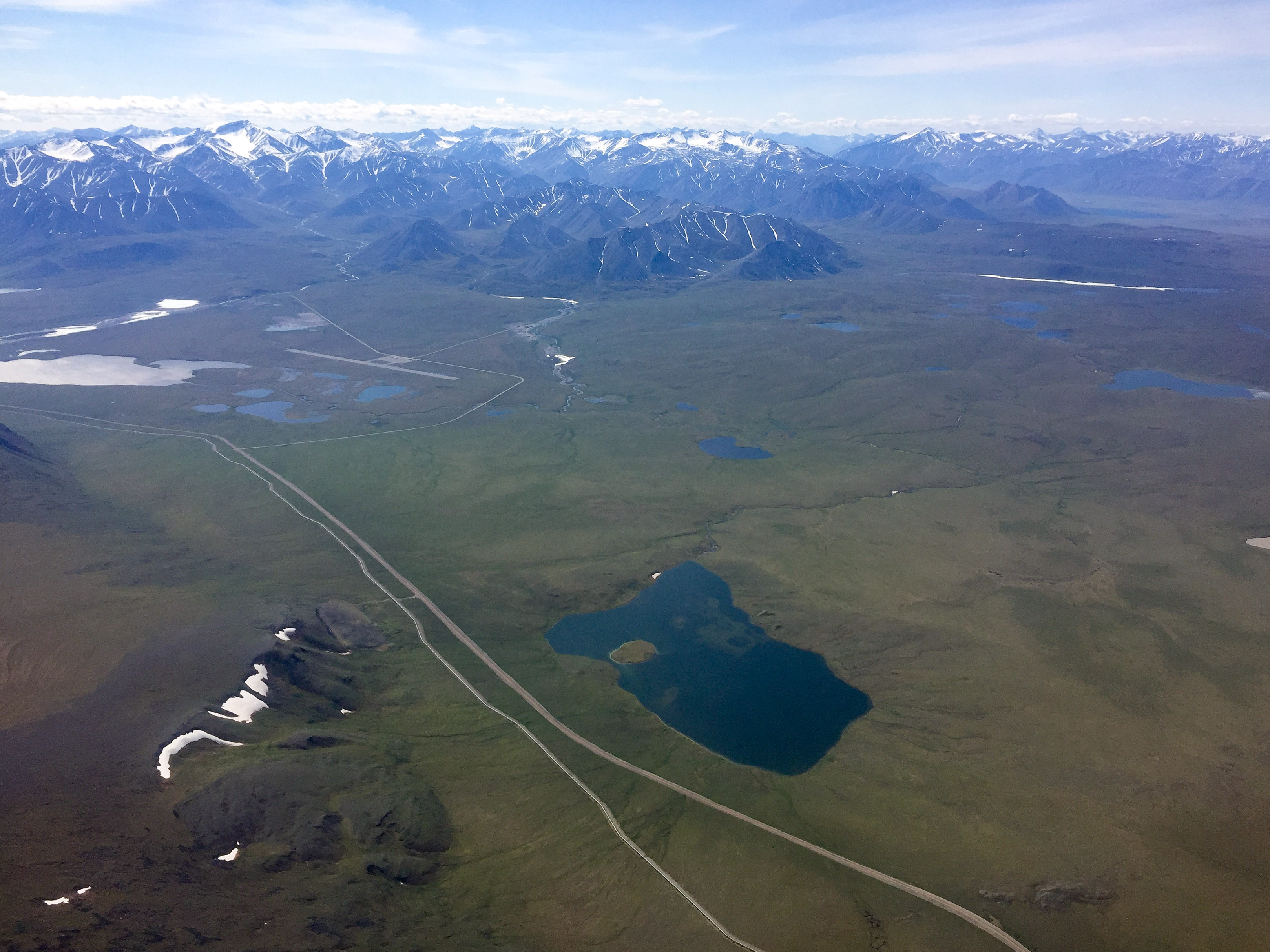

While it seemed the entire north slope was clear of clouds, the air was quite rough. Being so high I had enjoyed a smooth ride to the mapping area, but at 1600′ above ground level I was hit with a gusty 30 mph wind with lots of up and downdrafts. It’s nothing dangerous but it makes mapping a pain for a project like this. A major constraint for the project was to map the river in a single day so that changes in water level would not impact the map. To do this, the plan evolved into a following the river essentially by eye rather than plan blocks of straight flight lines over it to cut down on acquisition time, since the river changes directions as it flows and the ground resolution at 10 cm means a lot of flight lines. So not only am I trying to mimic the twists and turns of the river in a strong gusty wind but I’m also trying to maintain a constant altitude above it as I fly up and down the river. It’s both mentally and physically demanding work, like flying instrument approaches for hours on end.

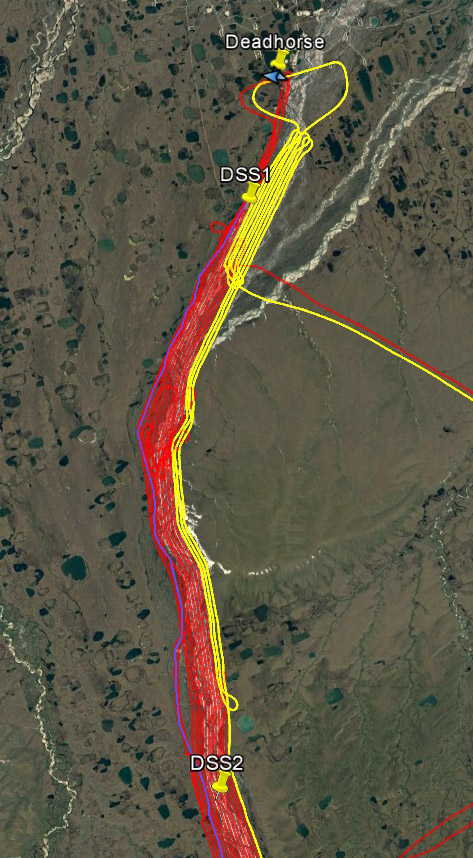

Despite the weather, work went well and I was able to get several hours mapping done before needing to stop for fuel in Deadhorse. I focused on mapping the area closest to Deadhorse first as I knew the coastal weather here was likely to be the most challenging in the area, and had hoped to get at least that coastal zone done today. But by now it was after 5PM and already a long day, so I got about the northern 10 miles of river done and headed to Kavik, not really wanting to deal with strong crosswind landings being much more tired than I already was. Fortunately conditions there were good and I arrived just in time for dinner.

Happy Valley, one of the field study areas.

Some of the aufeis that was plaguing the road, leftover from winter. We’ll be able to measure the volume of ice lost since I made the map last month, near its full extent from winter.

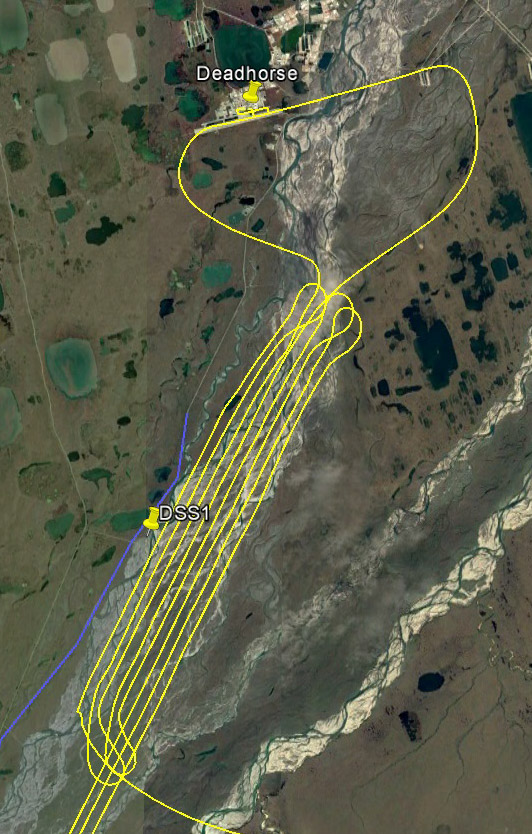

I focused on getting the area closest to the coast mapped in the time I had, as I knew this would be the most challenging area. The road is in blue.

Kavik is pretty conveniently located, with the added advantage of having good company.

Sue, and her seeing-eye dog Little Bawb.

The next morning was about as predicted, good weather everywhere with early morning coastal fog. The winds had died down substantially, so I spent a relatively pleasant morning finishing the southern section of the area, launching about 5 AM and returning to Kavik about 11. While winds were light, the air had a pretty good haze to it and a high overcast mostly. It reminded me of flying inside the ping pong ball in the Bethel area, just the ball here was much bigger with 20 mile visibility. It’s fine for flying and for photography, but it does reduce contrast a bit. While fueling up and jamming down some breakfast/lunch, I checked the forecast to learn that Deadhorse weather was no longer likely to clear up but at best become less marginal in the late afternoon and much worse over the next few days. So I began working my way down from the northern side of the southern end I had just finished, and turned from the lines early when I hit the coastal fog. As is often the case, the clouds there were at just the wrong height, a thousand feet higher higher or lower would have worked fine as it was by now a scattered to broken layer. In any case I mapped up to the cloud edge, until I finished the river to the south of it, saving the road and gap-filling lines until later so as to get the river completed in a day. At that point I began re-configuring on the fly.

Weeping Angel definitely was not happy about all the mosquitos in the plane. It took six hours of flying to kill them all. My biggest fear was that they were hiding in the camera port, obscurring the lens. Note the high overcast.

Where the river meets the road. Pretty twisty…

The floodplain is straighter, but wider. Water levels were high, but at least not at flood stage. It had rained quite a bit in the mountains the past few days.

That’s dust kicked up by a Helio Courier departing Kavik strip.

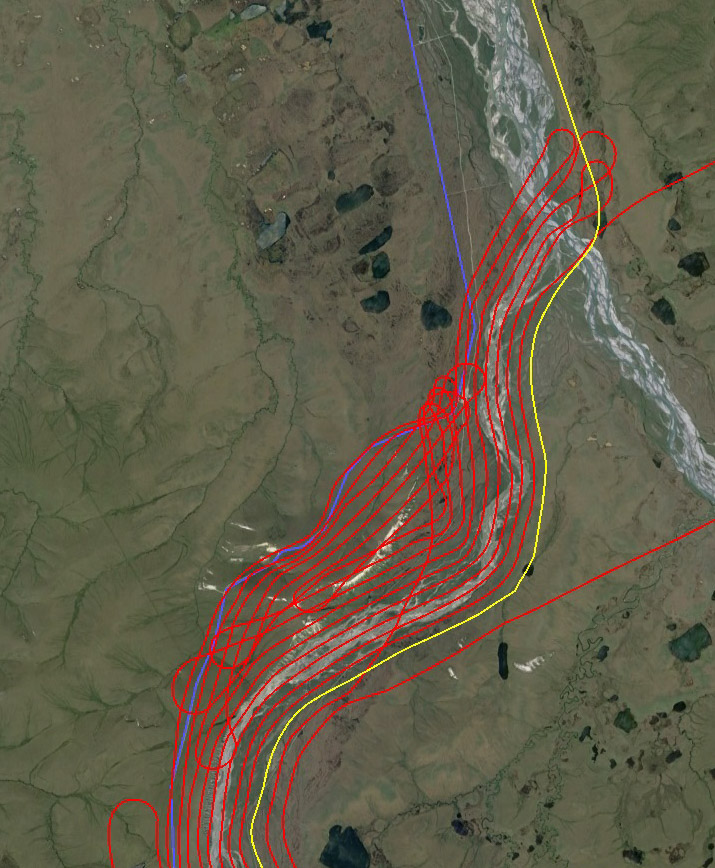

The next morning I focused on the southern end of the area (red lines), since the coastal side was shut down. That’s six hours of flying before lunch.

The goal here was to map the river and the road. For much of its length, the road is right next to the river, but it does diverge in places. Ideally we’d map a contiguous block including the spaces in between the river and road, but these were lower priority and in one iteration of the plan we had them mappable separately. So given that it was by now after 3PM and the weather was still marginal in the lower 25 miles of the study area, I went underneath the cloud layer to try to finish off the road at higher resolution since I could fly the road visually by eye, with the hope that while doing that the cloud layer might lift in the late afternoon sun despite the forecast, but if not I would try to do the remaining river in the same way using the new road lines to help me calibrate my line spacing. I could see that where the clouds began was at the edge of some sort of front, with broiling clouds over the ocean and above the high overcast I was in for much of the day was clear sky. So I had a good feeling that conditions would change, but no idea whether that would be for the better or not.

Joining two blocks of curvy lines — mouse-over to see the before and after lunch connection.

Flying low in this situation creates additional challenges. Exposure values are affected due to the bigger changes in lighting caused by variable cloud cover. The twists and turns I must make are stronger because I’m lower. I’m right next to a pretty big airport so I have increased traffic concerns and I’m trying to skirt their surface area when they are calling IFR. The cloud cover here is changing by the minute so I have to adapt and avoid more. And whether it was because I was so far north at the wrong time or because I hadnt showered in a week, both my gps are glitching out, so I’m now making repeat passes purely by eye so I have to remember a lot more. In any case, it was a handful but was going well enough, until it became clear that conditions in Deadhorse were actually improving but they were worsening to the south as the low cloud layer headed in that direction. So I switched gears again and flew back to the south to finish the road there, again flying it by eye, with the idea that at least I could get the road finished completely in case this was my last chance for the next month. That again went well enough, but soon the weather was changing yet again and it appeared that the strong haze that had been around all day might spontaneously turn into fog in every direction. Given the long term forecast and the temporal constraints of the work, I really wanted to fight it out, but I also really did not want to end up in a continental-scale fog bank while low on fuel. Deadhorse was ironically a bubble of good weather at this point, so I decided to land for fuel there and give the weather a chance to make up its mind.

The pipeline is underground here, but protected from the river by lots of earthworks. Those earthworks all require gravel, which all comes from the floodplain.

On that point is a small herd of musk ox. Guess you had to be there.

There was a strong haze in the air most of the day. By late afternoon it had intensified and become a little frightening.

Ironically Deadhorse was in a bubble of good weather when it looked like the slope was about to go under.

Fortunately by the time I was done fueling, I was treated to essentially perfect weather everywhere. I guess I was in a transition where just a degree or two of dewpoint spread change was enough to go from awful to perfect. There were still a few lingering clouds but they were thin and lower, so I was able to resume flying according to the plan. The challenge at this point because trying to remember where I flew low and how to merge that ad hoc flying with the planned mission. I had also flown more than 10 hours already so was trying to optimize the remaining time so to stay sharp and not really knowing whether the spontaneous fog layer would form again. But I think I got it all pretty well. I finished up the river as planned, then filled out as many of the gaps between river and road as I could before turning east to Kavik. A low cloud layer was by now forming across the tundra, and though I still had enough fuel to make it back to Fairbanks if needed, the thought of getting shut out of landing nearby after 12 hours of flying flight lines was not appealing. But I was relieved knowing that I had completed the project in less than 24 hours and was now ready to put my feet on the ground on my way to putting my head on a pillow.

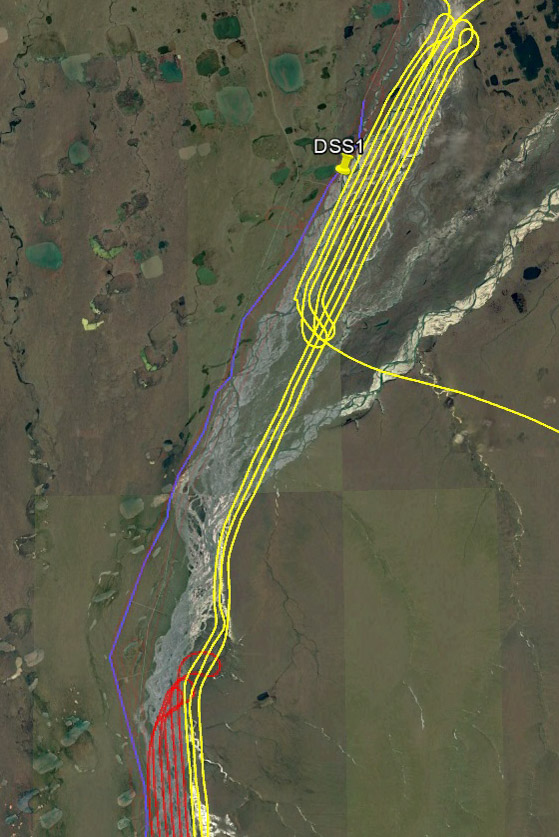

A cloud layer prevented me from getting within 25 miles of Deadhorse (red lines at bottom). The day before (yellow lines) I had tried to get as much as could done on the northern end. I started yesterday by getting outside the coastal influence (yellow lines at right), but was running low on time so I shortened them (top). After doing as much of the river as I could the next day, I snuck under the clouds to get the road done to the coast — mouse-over to see those lines.

Once the weather cleared, I was able to finish all of the river lines as planned and fill most of the gaps between river and road. One gap, just north of DSS2, remained unfilled. Click here to download the flight lines in Google Earth, where you can use the time slider to see the gyrations required to work the weather to acquire the area completely.

The clouds lifted after landing at Deadhorse and allowed me to slog out the remaining lines. That’s one of the material staging sites for road work on the right.

There were a few floaters lingering about, mostly over the aufeis.

But they were thin and low and easy to shoot through.

By my last line, they were gone.

Parting shot of Deadhorse on my way to Kavik.

The tundra to the east was being enveloped by a low, thin, pretty cloud layer.

Scenic now, by morning it was solid, thick and a pain.

The next morning it became clear that the thin cloud layer that formed the night before had indeed turned into a slope-wide fog bank. I was up pretty late the night before downloading and checking data, so had a lazy start in the morning. I wandered around camp catching up a little with Sue and fiddling with the plane. By 9AM I was thinking I was done for the day, but slowly it began to lift and I could see the mountains to the east. By 10AM it was looking good so I launched, only to find that the layer was still blanketing the tundra for a hundred miles that way. And while the mountains were out, I could also see cloud layers higher up in the valleys, so there was no chance of mapping the glaciers so I turned south and hoped I could sneak back into Fairbanks before the predicted thunderstorms started. I was only marginally successful with that, but successful nonetheless. After two days at a remote camp of 7 people and flying three hundred miles under the clouds without seeing a single sign of civilization, I had a bit of culture shock driving home — so many people, all strangers, driving madly to get somewhere in a hurry, traffic lights, box stores, will-work-for-food signs, it felt a bit overwhelming. I think what I enjoy most about these acquisitions is the single minded focus of trying to succeed against the weather and that most of the people I bump into, whether on the ground or in the air, are people that I share similar interests with trying to do the same. Weather may be capricious but its not malicious, it’s unforgiving but its not spiteful. When you compete against the weather, the weather never loses, but it doesnt mind you winning too. Civilization, by contrast, pits us against each other and is little more than a sorting process to rank individuals on a spectrum of winners and losers using an elaborate network of carrots and sticks that we are essentially forced to use or obey. And with nearly everyone a loser to some degree on that spectrum, there is essentially no predicting the angry left turn any one of these people might take and the purposeful havoc they might wreak. While I’m always in a minor state of terror while flying due to the number of things that can go wrong, I feel at least that it is within my power to mitigate those risks. So even though the statistical chances of instant random death caused by some nut job in civilization are much lower, I think its the fact that there is simply no way to mitigate those risks that makes them seem more frightening. Regardless, I’m at least relieved to say that soon we will have a great new map of a special place in the world that will be used to help us better predict our impacts on that place, and even more relieved about going to bed and sleeping in.

I had hoped to map the glaciers surrounding Peters Lake on my way out, but a low ground fog and valley clouds prevented it. It was pretty challenging just getting out of there.

The fog lifted at Kavik, but was still low to ground to the east. The glaciers were above them, but there was no going over this and clouds were also higher up in valleys.

Such a dynamic landscape in so many ways.

But Weeping Angel was saying it was time to go.

We tried climbing over the buildups to the south, but already at 11,000′ it was a losing battle so we had to go under.

By the time we reach the south side they were already letting loose.

The Yukon valley was surprisingly open still. Caught this one taking his puppy for a walk.

The Fairbanks area was surrounded by some pretty big ones. I was relieved to learn that I wasnt the only one not liking these, as a bit further west along the road there was a lot of commercial air traffic trying to stay out of each other’s way while avoiding them. Not long after I landed these were making lightening.

May not look like much, but that’s 25 hours of flying in two days.